Ellen Bauerle and dpotter

August 8, 2015

by David Potter

On May 2, 2015, two men boxed for thirty-six minutes, and each made an enormous amount of money, splitting a record purse of $300 million. Fans may not have seen the greatest fight of all time, or anything close to it, but they did get to boo the winner, Floyd Mayweather, when he strutted around the ring after he was awarded the unanimous decision. The political ambitions of the loser, Manny Pacquiao, do not seem to have been damaged by his defeat. There are already rumors of a rematch. Tiberius Caesar would have been appalled.

On May 27, 2015, a series of indictments was issued against leaders of the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) for a wide range of corrupt activities in connection with the world’s most widely viewed sporting event, the World Cup. The modern notion that major sports organizations should claim to be self-policing and effectively free of governmental oversight—a privilege also asserted by, for instance, professional sports leagues in the United States and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA)—descends from the early days of these institutions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Claudius Caesar would have been astounded.

Tiberius Caesar rarely gets much credit for innovative thought, yet he is the first person who sought to restrain runaway spending on sport. He set limits on the cost of public spectacle—gladiatorial combat to be specific—and faced the question of what might be reasonable public expenditure on sports. Claudius likewise gets little credit for creativity, but it seems to have been in his reign that imperial regulation of independent athletic associations became the order of the day. Although dossiers of imperial letters that have come down to us on papyrus refer to earlier grants of privileges from the Augustan era, the dossiers begin with a letter of Claudius.

The half-century before Tiberius took the throne as sole emperor in 14 CE was a period of extraordinary experimentation in public entertainment. Mime, with male and female performers, was becoming an increasingly important genre; women had started appearing as gladiators; new mythological dance routines—pantomime—had become amazingly popular; professional Greek athletics were increasingly interesting to Roman audiences; and there were now occasional aquatic spectacles. In summing up the events connected with the opening of Rome’s first permanent theater in 55 BCE, Cicero remarked that everything Pompey had to offer, people had seen before (Ad fam. 7.1). This may have been something of an exaggeration—an elephant massacre on the last day had been as novel as it was ill-advised—but the point remained that the aspiring autocrat needed to show some originality. Augustus had been determined not to make Pompey’s mistake.

Augustus’ entertainment boom was connected with a building boom. Rome’s first permanent amphitheater had gone up in the early twenties BCE, built by the important general Statilius Taurus on the Campus Martius; a massive new theater, named for Augustus’ preferred successor, Marcellus, had gone up in the same area as had another new theater, named for the son of a man who had helped Augustus to the throne. The Circus Maximus, home of Roman chariot racing, had been vastly improved; and a facility had been constructed on the Tiber’s western edge (not far from where Vatican City is today) to house spectacular aquatic entertainments.

In 14 CE, there were plenty of new facilities, and these facilities were intimately connected with the creation of the new political order. The revamped Circus Maximus, incorporating an Egyptian obelisk, was a monument to the victory over Antony and Cleopatra at Actium, as was Statilius Taurus’ amphitheater (Taurus had commanded the ground troops during the campaign). Augustus himself had been largely responsible for the rise in the popularity of pantomime, to which he appears to have been addicted. The problem was, going forward, who would pay? Augustus seems to have paid premium rates, but who else could do this? Augustus had faced problems convincing people to hold public office since that would require them to put on expensive games, and he had found it necessary to subsidize the spectacles of others (Dio 54.2). Could that continue?

In addition to the financial issues there were issues of public order. Now that games were not being offered in connection with a notionally competitive political system, fan attention was turned away from overtly political partisanship—we hear of not a single riot in connection with a sporting/theatrical event in the Republic—and toward the success of the performers. Although we know, mostly from Cicero, that politicians would judge their popularity on the basis of partisan displays at public events, these displays do not seem to have turned violent (Pro Sest. 106; 115-16). The contrast between what happened in the years when Rome did not have public security forces and what happened when it did could not be more striking. One of the first things we hear about after Tiberius became emperor was that he had to use troops to quell violent confrontations between the fans of rival pantomime artists.

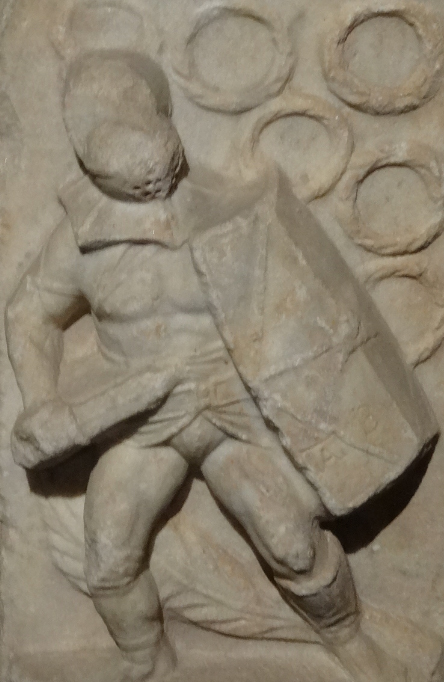

Tiberius doesn’t seem to have much liked the theater, and he had been a victim of early Augustan price inflation when he sponsored games in memory of his grandfather, Drusus, in the twenties. He had paid each of two veteran gladiators 100,000 sesterces to return to the ring for a duel of champions—there would have been a substantial prize on top of this for the winner. To put that sum in perspective, Augustus was paying his legionaries around 900 sesterces a year, so less than a half hour of a gladiator’s time (fights seem to have lasted about 15 minutes) was worth about 100 legionaries (Suet. Tib. 7.1). Nowadays that might seem cheap. Mayweather’s estimated $180 million purse would have been enough to pay the annual salaries of more than 8,000 privates in the US Army (basic pay for a private first class with less than two years’ experience was $21,664.80 in 2014), but Tiberius would have thought that soldiers were more important. With the budget straining to meet military pay, the emperor instituted limits on the number of gladiators who could appear and the risks they would face, while fixing maximum expenditures for games as a whole (Suet. Tib. 34).

Tiberius seems to have recognized that risk was a factor driving costs. Although fights to the death were uncommon among gladiators, it is striking that two of the references we have to the practice come from the late Republic and early Empire (our other references, outside of Rome, come from the Greek east in the third century CE) (Suet. Caes. 26; Sen. Maior. Controv. 9.6.1). Indeed, the late Republican fashion of high-stakes, winner-take-all contests rather closely mirrored the political system in which these contests took place, and pushed costs upwards. Under Augustus, when costs continued to rise even though the main driver for earlier price increases—the enhanced possibility for success in a reasonably open electoral system—had been eliminated, the entertainment system fell out of alignment with the political/economic system that supported it. But the games had to go on, and the Augustan subsidies paid for 240 gladiators a year—which, even if he was paying, on average, a tenth of what Tiberius paid, would have amounted to the cost of about half a legion. The choice Tiberius faced was thus either to continue Augustan-style subsidies, at a time when there were actual constraints on the budget, resulting in problems meeting pension obligations for veterans, or to find a way to change the system.

If Tiberius were to change the cost structure, which was driven at least in part by risk, he was also going to have to alter the risk factors behind the most dangerous contests. This is easier said than done. The NFL and NCAA may claim that they are deeply concerned about the possibility of serious head injuries, but that realization is coming rather late in the day, and penalties for blatant fouls are not intended to limit the essential violence of a contest. Indeed efforts to combat concussions for players other than quarterbacks should be contrasted with the far more effective efforts to prevent injuries to quarterbacks. One hates to suggest that this is because an injury to a quarterback is likely to hit an owner’s pocket harder than one to a wide receiver.

Tiberius went well beyond the NFL and NCAA in trying to limit violence through rule changes. Augustus had already tried to restrict fights that would compel gladiators to compete until one or the other could not continue; efforts to further regulate violence were encouraged by the embarrassing display of enthusiasm that Tiberius’ son, Drusus, had put on while watching what is described as a particularly bloody gladiatorial exhibition in 15 CE (Tac. Ann. 1.76.3). Complaints about Drusus underscored the fact that the costs, reputational as well as financial, were out of line with what could be anticipated as the benefit accruing from the spectacle.

It is arguable that the changes Tiberius brought to ancient entertainment swung the pendulum away from Augustan practice a bit too far and too fast, since he seems to have stopped subsidizing games. The result was that there was a dearth of gladiatorial combat in Rome itself. Unlike municipal magistrates and provincial magnates, whose contests for influence were genuine and were influenced by the popularity of games they sponsored, Roman senators no longer received a tangible benefit from funding games and they seem to have gotten out of the business as fast as they possibly could, while lowering the risk may have encouraged members of that order to do something that would appall the emperor: fighting as gladiators themselves. From the point of view of some members of the senatorial order, the games, no longer a path to power, became instead a venue in which to protest the stuffy stress on “old time morality” that was increasingly a feature of the imperial regime.

People who sponsored games in antiquity played the same role in sport that team owners do now. Modern analysis of those who buy sports franchises shows that, whatever the ego boost someone gets from buying a team, the owner is generally also in the business of making money. Even Howard Schultz, who owned the Seattle Super- Sonics for five largely game-losing and money-losing seasons, sold the team for $90 million more than he had originally paid. One of the best investments the Chicago Tribune Companies ever made was in the Chicago Cubs, purchasing the team for $20.5 million in 1981. The Cubs were sold in 2009 for nearly $900 million (and they still have not made it to the World Series). The ancient equivalent of owners, the individuals who paid for the spectacles for which, generally, they could not charge, had other sorts of interests. They funded games in conjunction with years in office, which effectively gave them access to people more important than they were (e.g., provincial governors). Imperial restrictions on how much they could spend on these games lessened the chances that the average “owner” would go broke putting on his games, while these same restrictions allowed some flexibility for those people who wanted to make a bigger investment to appeal for permission to exceed the limits. Obviously individuals put different values on the ability to schmooze at the games, but that is not the only thing that is significant about price controls. Price controls meant that imperial officials had a regular look at what was going on at the local level. When disputes arose, as they seem to have done with some regularity between different groups involved in the games, they ended up with the emperor.

Writing in the early second century, the historian Cornelius Tacitus reports a few events that may have been remembered as key moments justifying further oversight and thought about the role of government in sport. One was the case of the freedman who tried to make up for Tiberius’ disinterest in funding games by putting on his own display in a badly built amphitheater at Fidenae (it collapsed, killing thousands) (Ann. 4.62). In another case, Tacitus recalls a riot between groups of rival fans that broke out at a gladiatorial spectacle in Pompeii during Nero’s reign (Ann. 14.17). Others might recall that Tiberius’ vast savings had the unfortunate effect of providing the cash Caligula needed to solidify his claim to the throne after the death of Tiberius, who did not want him as a successor. Caligula put on three months of games, using money he took from Tiberius’ treasury. (Suet. Cal. 14).

Tiberius was good with money. He confronted issues integral to the structure of any major entertainment industry—how to balance the interests of owners, fans and performers—with considerable imagination. He managed to break an upward spiral of cost by limiting risk to performers. The further interventions of other emperors meant that athletic organizations had to conform to what emperors determined was the public good.

Claudius seems to have been a key figure in establishing broader imperial oversight. He was a good deal more sympathetic to the games than Tiberius had been, he liked watching gladiators and, at least for games at which he was present, would allow fights to the death (Suet. Claud. 34). On the other hand, he also understood not everyone could afford what he could afford and that if games were going to be run successfully, the knowledge of professionals had to be harnessed to serve the interests of the state. The system of price controls for gladiators that Tiberius had set up was maintained if not strengthened under Claudius, so much so that early in Nero’s reign a senator might complain that this was all people talked about in meetings of that august body (Tac. Ann. 13.49). As for the professional associations of Greek athletes, which played a FIFAesque role in the organization of events for their members, the fact that the first document in dossiers listing privileges for their members date from Claudius’ reign suggests that it was Claudius who imposed new order on a system that appears to have suffered from benign neglect for a long time prior to his taking the throne. Later emperors would tinker with the system—Trajan, for instance, would require athletes to show up at a city from which they were claiming a pension, Hadrian stated that all they needed to do to start the payment process was send a letter—but no more. Athletic institutions could only be self-governing if their actions remained within parameters set by the state.

The Roman solution is quite different from the modern solution, which allows independent associations to seek new revenue streams no matter what the impact on the players. The NCAA’s deal with ESPN to create a national championship playoff in college football is a case in point: it is arguably good for ownership, good for some fans, and not good for the players in their role as student- athletes. Similarly, the deal between the NCAA and CBS/Turner Broadcasting to show the men’s basketball tournament is good for the networks and NCAA, while it tends to bring a hiatus to intellectual life on college campuses for substantial stretches of the month of March. College presidents, who currently seem to find it next to impossible to influence the NCAA, might want to consider the fact that two thousand years ago, a Roman emperor found a solution to expenditures that he saw as threatening the core values of the imperial system.

Tiberius was not good with people. Whether it was in refusing to sponsor games, or even celebrate a second funeral for his adoptive son and heir, Germanicus, he lacked sympathy for people who found the rituals of public spectacle meaningful to their own lives. Whether the occasion was a funeral or chariot races, spectacles bring people together; they create bonds of community; they spawn powerful emotional reactions. Tiberius did not care and it would take the better part of the next century before a balance could be reached between excess and rational expenditure, which does appear in the succeeding Flavian and Antonine ages, and which contributed in no small way to the stability of those years as emperors made rational use of the tools Tiberius had devised. It is not accidental that the return of excess under Commodus led directly to his assassination and the wars that followed. College presidents might want to keep that in mind as well. So might the prospective sponsors of another fight for Floyd Mayweather. As for FIFA, we might just want to imagine what an exit interview between Tiberius and FIFA’s outgoing president, Sepp Blatter, would have looked like.

Further Reading

D.G. Kyle, Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World (2nd edition) (Oxford, 2015)

D.S. Potter, The Victor’s Crown (London, 2011)

T. Wiedemann, Emperors and Gladiators (London, 1995)

David Potter is Francis W. Kelsey Collegiate Professor of Greek and Roman History and Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, University of Michigan. He has published books on ancient sport, the emperor Constantine, and the empress Theodora. He can be reached at dsp@umich.edu.