In the third post in our independent scholars series, Ann Patty discusses her late in life discovery of Latin and her love of learning, teaching, and promoting Classics.

I began to learn Latin as I approached the age of 60. After the recession of 2008 my highly leveraged company forced me into early retirement. I had been an editor and publisher for thirty-five years, an all-consuming career that kept my mind engaged and provided me with a community, a passionate purpose and a strong identity. Suddenly all those things were taken away. I retreated full-time to my country house, also forfeiting my identity as a New Yorker. I became an exile. I had participated in the chattering classes my entire adult life. On my rural plot of land in the Hudson Valley, the only chattering to be heard was that of chipmunks and squirrels. I needed words.

Words were my first and perennial friends. I’ve kept word lists since I was a child, and I still do. When I discover a new word, I feel a surge of delight. Soon after my retirement I discovered the word concinnity—the harmonious arrangements of parts, especially in writing, an expression so beautiful it rises to the level of music. I knew Latin was behind that word, as it is behind two-thirds of our English words. Latin is the home base of English words and grammar. If words were my first love, grammar was my second, a stern mistress whom I had served happily for all my years as an editor.

There was one thing, I realized, that I had missed in my life-long devotion to words and grammar, and that, of course, was knowing Latin. I had taken only one, laughably easy required Latin semester, in the seventh grade. The only thing I remembered from it was the declension of agricola. I researched local public colleges. I was alarmed to discover that none of them offered Latin. Nor did a nearby Catholic college. I contacted Bard College, where the professor didn’t allow auditors in beginning Latin. Finally I contacted Curtis Dozier at Vassar. He welcomed me to audit his class.

Like every beginning Latinist, I spent the first year cramming fundamentals. I travelled the country roads to Vassar four days a week, chanting conjugations. I counted forms of personal pronouns rather than sheep when sleep eluded me. I made vocabulary flashcards. I considered Latin my part-time job. Between class, commute and study, I was filling at least 20 hours a week. I was no longer a bored and lonely exile. I was now a discipula Latinae. It was not easy. I had forty years on everyone in the class, and although I had always considered myself a smartie, in Latin class I was a dummy.

Nevertheless, I persevered and as the semester continued, I grew more and more enchanted. New grammatical concepts hit me like illuminating spotlights: The passive periphrastic was the form of cravenness (Latina mihi docenda est!). The dative of reference with genitive force was a useful intensifier (Latina mentum mihi exsuscitet). Ablatives– of separation, of attendant circumstance, of degree of difference, sent me searching for the ablative structures of my life. I fell in love with the much- maligned Ablative Absolute. In two short words, it could transition from one episode to another, end one era and begin anew. My career had become an ablative absolute: Cursu perfecto, facta sum discipula Latinae.

Because I was in search of a new community, I decided to follow my Latin pursuit wherever it might lead me -- or, I should say, wherever Internet searches might lead me. First I found the Paideia Institute. I had taken two years of classes at that point and thought, why not try speaking Latin? When I received my reading packet, my heart fell. It would take days for me to translate even one page! How could I discuss these works in Latin, no less! When I wrote Jason Pedicone, he reassured me, and, being the entrepreneur he is, looked at my resume and insisted I come. “I really want to attract non-academics, please come, gratis. People are kind, you’ll be fine.” And I was, because I was in the beginner’s group. That weekend led me to joining Paideia’s advisory board and introducing Jason to Stephen Haff, of Still Waters in a Storm, which led to the creation of the Aequora. I was actually doing good, if not doing well (my spoken Latin, despite a weekend at Salvi in West Virginia, a week at the Boston University’s summer conventiculum in Massachusetts and three Paideia Living Latin in New York weekends, is still less than proficient – I remain in the beginners group

I began writing a book because I had to. I had no Latin community beyond two or three hours of classroom a week, and my friends were beginning to complain when I recited bits of poetry or tried to interest them in the epexegetical infinitive. One of my friends, whenever I began anything Latin-y would say “Oh Ann, are we talking about Latin again?” I needed an interlocutor. Latin was not only my subject, it also became the ghost talking back to me on the other side of my computer screen.

I was terrified when my book was published that academics and professional Latinists would scoff at me and take me to task as a dilettante. Instead, the very opposite has happened. It seems Classicists like amateurs who love their subject – witness my being here! Only last week, a retired Latin professor sent me corrections for ten errors he’d found in the paperback edition of my book. This was an amazement to me: I had paid one Classics professor to correct the Latin before galleys; another had graciously sent me four pages of corrections. After publication, the writer of a well-known Latin text sent me another four pages of corrections. All were fixed in the paperback edition; yet there were still more to be found! That’s one of the things I love about Latin; it’s a never-ending learning process. To perfect my Latin, it seems to take a classical village.

Last fall, five years into my studies, I took another class with Curtis Dozier, my first professor. We’d become friends, but I hadn’t taken a class with him in four years. The semester featured the lyric poets, most of whom I’d sampled in other classes. At the end of the semester, I asked Curtis how he would rate me as a Latin student. Ever the gentleman, he paused and said, “You’re certainly not among the worst,” then a little smile and “probably not among the best either.”

Nevertheless, I have now added magistra latinae to my new identity as scholar and writer. Three years ago I began offering a free weekly Latin class for teens at my local library. None of the public high schools in my area offers Latin; it was the first thing to be cut in the recession. This fall I’ve lost my three dedicated teens, either to overfull high school schedules or boarding schools.

Currently, I’m teaching elders. Through a Lifelong Learning course at a local State College, I now have six dedicated Latin students, all around my age, all retired. And only one of them (woe is me) was inspired by my book! One man loves Roman History, another is interested in word derivations. One woman wants to understand botanical and ornithological terms. Another, like me, still fondly remembers diagramming sentences. All of them had a bit of Latin, either in high school or through the Catholic Church. They say they’d always wanted to learn more Latin, but didn’t have time before retirement. Last week, I asked 70 year old Johannes, how it was that he always completed his homework so perfectly. “Remind me how much Latin you had before this,” I asked. “Just two years in high school, longer ago than I wish to say,” he answered. When I expressed my amazement and asked, “How is it that you’re so good at this?” he said, “I have nothing better to do.” Nor do I, nor do many retirees.

I believe there is a large untapped market for learning Latin among seniors. One Michigan professor friend told me about the program at Wayne State University which allows seniors to take undergraduate classes for a nominal fee. Because they are officially registered at the school, their attendance counts towards increasing class size, and the administration doesn’t distinguish between the low-freight seniors and regular students. What a brilliant way to prevent an administration from cutting the classics due to low class size! Many public institutions have auditing programs for seniors, and many professors at private institutions accept auditors. Perhaps some might take a page from Wayne State’s program to strengthen their classics program.

I have come to suspect, from reviews of my book, and the many emails I’ve received since its publication, that only those who have some knowledge of Latin, whether scant and great, past or present, are interested in reading about the language. Nevertheless, there continues to be a large market for classical scholarship: witness Greenblatt’s The Swerve, Mary Beard’s SPQR, Daniel Mendelsohn’s recently published an Odyssey. One bookseller wrote to me suggesting that I write historical novels or mysteries set in Ancient Rome. “They’re very popular these days,” she assured me. I’m not becoming a novelist at this late date, but I will continue to be a Latin scholar and an enthusiast for the classics. I plan next to turn to Ovid’s Tristia and Ex Ponto to explore exile, both ancient and modern.

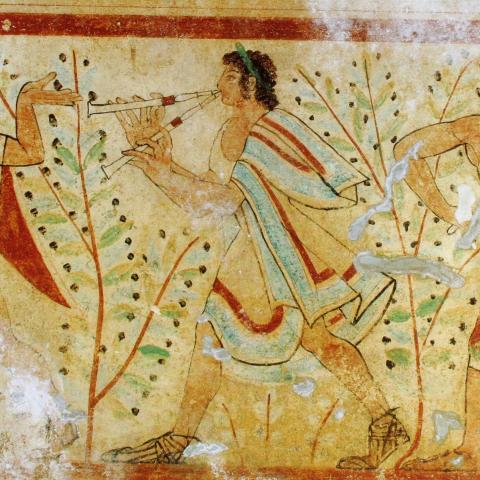

Header Image: Dancers and musicians, tomb of the leopards, Monterozzi necropolis, Tarquinia, Italy. UNESCO World Heritage Site. Fresco a secco. Height (of the wall): 1.70 m. 475 BCE. from Le Musée absolu, Phaidon, 10-2012, photographer Yann Forget. CC By 1.0.