Christopher Polt

July 18, 2019

The United States was more than a century old before it saw its first play staged in Latin. What follows is a story about its producers’ struggle for recognition and the external factors that doomed it to obscurity. Beyond a footnote in theatrical history, the 1877 production of a Jesuit Latin play at Boston College offers a glimpse into the fraught politics of education in the United States in the late 19th century, the origins of the modern college elective, and a form of Classical curriculum that might have been—if an ugly fight in Boston had turned out differently.

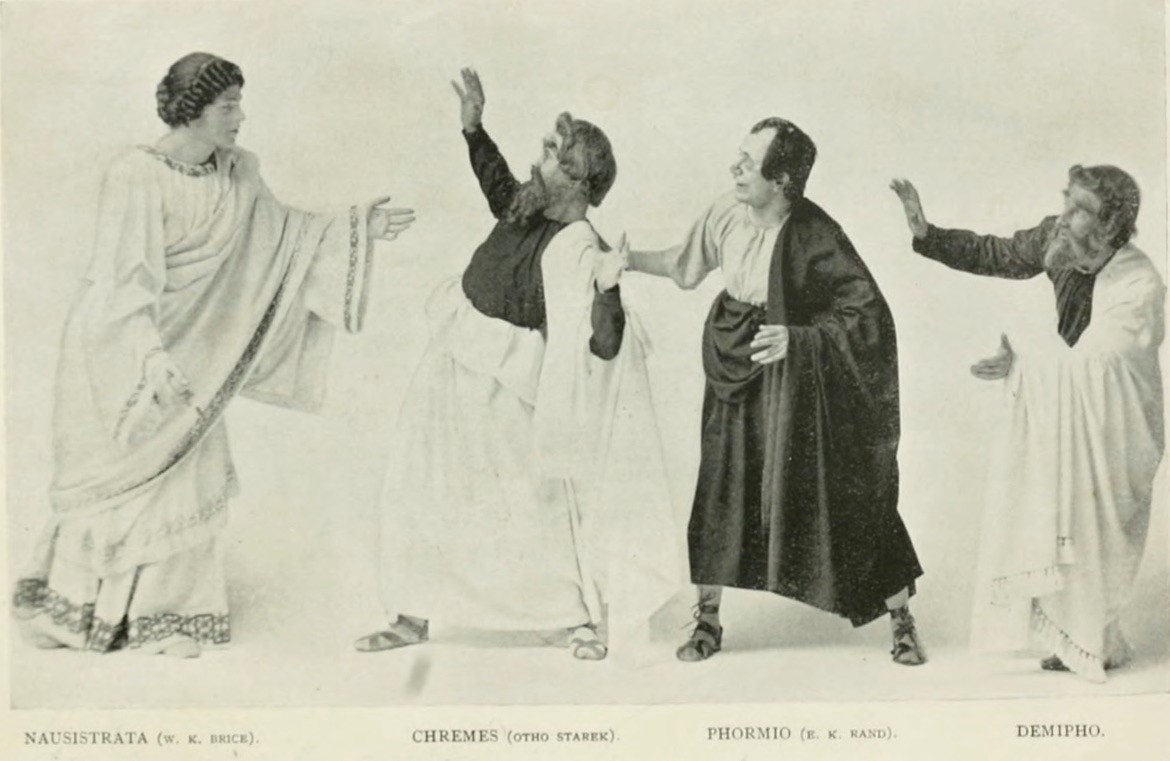

In April of 1894, Harvard’s production of its first Latin play had set Boston buzzing. The event even rated a couple columns in the New York Times, which remarked:

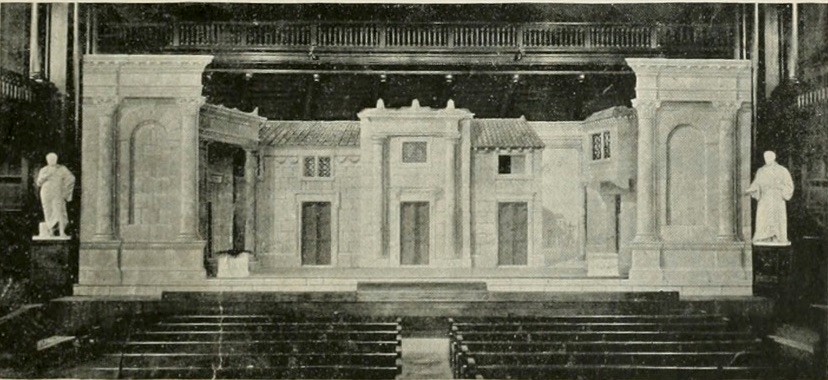

Latin plays have been given in this country and in England, but never with the careful study of detail bestowed upon the Phormio of Terence, to be produced by Harvard students in Sanders Theatre this week… Educators from all parts of the country are expected to witness the production.

On April 20, 1894, the Boston Daily Globe recorded that it was a star-studded event, attended by the Governor of Massachusetts, Alice Longfellow, and Swami Vivekananda, among many others. A couple months later, J. B. Greenough, one of the Harvard professors who helped organize the production, wrote in The New England Magazine with justifiable pride about the event, even offering a miniature history of Greek and Latin drama in modern Europe and the U.S.:

This custom of plays in schools was not brought to this country by our ancestors, and has never been introduced until very lately, so that our classic plays are essentially a new departure, and do not connect at all with the old traditions. The first attempt, so far as I know, to produce a classic play in this country, was the Greek play [Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex] at Cambridge, in 1881, though it is quite likely that Latin plays, classic or other, have been performed privately in Catholic colleges. The Oedipus at Cambridge has been followed by others in various parts of the country, notably by the admirable performance of the Antigone by the girls of Vassar a year ago. The first Latin play in this country was given by the students of Michigan University, at Ann Arbor, and later at Chicago, the Menaechmi of Plautus.

Greenough was correct that the University of Michigan had preceded Harvard in staging a Latin play—twice, in fact, since eight years before Menaechmi, Michigan students put on Terence’s Adelphoe in Latin for their 1882 Commencement. This was an event that The Michigan Alumnus called “epoch-making.” He was incorrect, though, that Michigan was the first, and some seemingly off-hand remarks in his account point to a much larger conflict in American higher education than who claimed the mantle of first Latin play.

In fact, that title goes to Boston College, one of the Catholic schools that Greenough waves off. BC produced a neo-Latin comedy in 1877 for its own first Commencement. Greenough’s quip about “Latin plays, classic or other” suggests he was well aware of it, since he had been a professor of Latin at Harvard for several years by the time of its production and it was indeed one of these “other” Latin plays by Catholic colleges, which he so readily dismissed. And contrary to Greenough’s claim that Latin theater was a novelty with no links to ancestral traditions, Boston College’s play asserted a continuation of an educational practice with roots in the 16th century.

The Jesuits’ core curriculum, the Ratio Studiorum of 1599, encouraged the production of both tragedies and comedies in Latin at least once per year, with the aim of improving students’ memories, public speaking, language skills, and moral formation. An earlier 1586 draft of the Ratio even promoted such performances as good P.R.: “Our students and their parents become wonderfully enthusiastic, and at the same time very attached to our Society when we train the boys to show the result of their study, their acting ability and their ready memory on the stage.” And the Ratio simply formalized a practice that had already become entrenched. The first Jesuit university, inaugurated at Messina in 1550, staged a Latin tragedy a year after studies formally began there and put on its first Latin comedy in 1558.

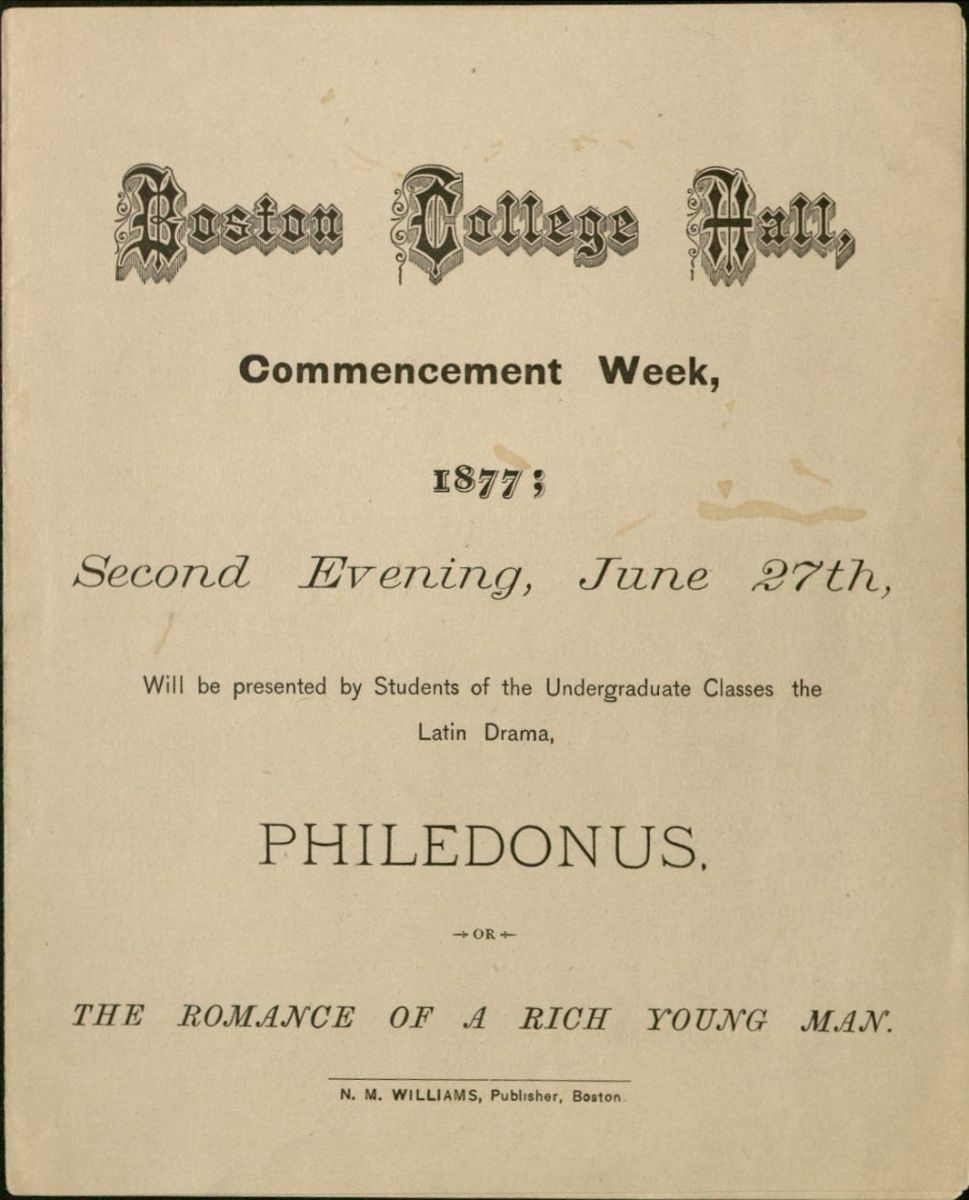

To mark the occasion of its first Commencement in 1877, Boston College organized an exciting program of activities looking to the future and to the past: a demonstration of the new-fangled telephone that Alexander Graham Bell had just invented at his Boston lab, a debate about the best form of government (democracy won, of course), and the first production of a play in Latin in the United States.

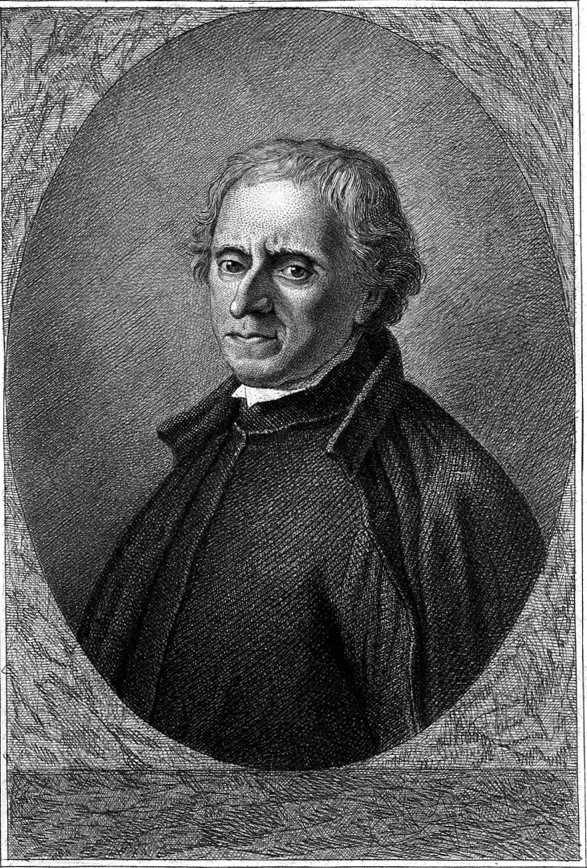

Students chose to stage the Philedonus, a Latin comedy written in 1727 by Fr. Charles Porée, a French Jesuit known today, if at all, as one of Voltaire’s most beloved teachers.

The plot of Philedonus (literally, “The Man Who Loves Pleasure”) is delightfully heavy-handed. The naïve young Philedonus travels from his home in Italy to receive an education in France, but Parisian luxury, wicked books, and a parade of wastrels and parasites soon endanger his good character and immortal soul. But he is saved in the nick of time! He watches his friend Erastus (“Loverboy”) die of the same vices that Philedonus had subjected himself to and receives an admonitory message from his saintly mother, who also happens to be dying. He repents of his worldliness and resolves to return home, rescuing his friend Oenophilus (“Wine-lover”) along the way.

Philedonus is not subtle, to say the least, or particularly well-known. But its choice as BC’s first Latin play was meaningful, especially for an upstart college struggling against widespread anti-Catholic sentiment that pervaded the predominantly Protestant New England schools. Porée was, as all Jesuits of the time, deeply trained in the Classics, and wrote a number of plays based on characters, themes, and forms adapted from Greek and Roman drama. He was also a great apologist for the educational and moral value of theater, defending it against serious contemporary criticism and censorship in his 1733 speech, Theatrum sitne vel esse possit schola informandis moribus idonea (“Whether theater is or can be a suitable school for the formation of manners” — his conclusion is, as you might expect, “Yes”).

On a practical level, Philedonus was an apt selection for college students going out into the world. It warned them of the dangers of alcohol, luxury, and impiety, while also reminding them of the power of repentance and redemption. And ideologically, it was Jesuit education made manifest to a public audience, a display of the value of humanistic theater and of Latin literature that showed how both could be vital for “real life” beyond college, by a Jesuit priest and playwright who had passionately taught that same lesson in Paris 150 years before. The audience was thoroughly receptive, proclaiming the show “a prodigious success.” In his diary, Fr. Robert Fulton, President of Boston College, expressed his delight with equanimity: “The boys were quite intelligible — no mistake in prosody.”

Of course, not all theater was equally beneficial in the eyes of the Jesuits, and the Latin plays of Plautus and especially Terence were almost irredeemable. The Jesuit Ratio restricted which works should be read by students:

The provincial must conscientiously take every precaution to keep out of our schools works of the poets and any other books which may be harmful to character and morals, unless everything objectionable in matter and style has been expunged. If, as in the case of Terence, this is impossible, it will be better not to read them at all than to expose our pupils to spiritual harm” (trans. A. J. Farrell, The Jesuit Ratio Studiorum of 1599, 11).

The Society’s founder, Ignatius of Loyola, had commissioned his colleague Fr. André des Freux to prepare acceptable editions of Terence, but the latter complained that this was impossible for him, “because the poison was often in the very structure and argument of his works” (Farrell 181 n. 21). Staging his Adelphoe or Phormio, as Michigan and Harvard would later do for their first Latin plays, would have been beyond the pale.

In the years after their production of Philedonus, the performance of Latin plays would become a touchy subject for BC students, who saw their accomplishment being erased through omission and the incorrigible Terence taking the spotlight on the American stage. In its December 1893 edition, Boston College’s first student newspaper, the Stylus, dryly noted the hubbub about Harvard’s Phormio:

There is a much-talked-of coming Latin play to be given by the Hasty Pudding Club of Harvard in the near future. This is the first attempt which the University across the Charles has made in Latin dramatics. Boston College has often and successfully produced plays in the tongue of Plautus.

In May of 1896, the same paper got a bit punchier when Boston University started horning in on the act.

Some of the Boston papers have lately displayed either great ignorance of contemporary history or prejudice greater still, in claiming that the Boston University has the honor of producing the first Latin play in this country. That identical play of Plautus has already been put on the stage several times by Catholic Colleges.

It cites the May 15, 1896 edition of the Boston Globe:

Much as the University students are to be congratulated upon the latest bent of their enterprise, some of the credit assumed and insisted upon in the various lengthy announcements of the first production of the play, which recently appeared in the Boston papers, must be detracted from

It also remarks that BU was “following the late example of Harvard and the earlier one of Boston College, where the first play in the language of ancient Rome was given.”

The eyebrow-raising accusation of “great ignorance…or prejudice greater still” points to more than frustration at their Latin production not being recognized. The country, and Massachusetts in particular, was roiling with anti-Catholic sentiment, and Jesuit schools such as BC and Holy Cross were fighting for survival in the predominantly Protestant landscape of American higher education. And ironically, at exactly same time Harvard was vigorously promoting its own Latin play, the school was in the process of ending the traditional Classical curriculum that had dominated education in the United States through the 19th century — and sounding the death knell of Jesuit education as it had been practiced for 300 years. In the 1880s, Charles W. Eliot, Harvard’s longest-serving and most consequential president, introduced a college curriculum based not on a set of subjects shared by all students, but on electives from which students could pick and choose as they developed a personalized course of study (if this system sounds familiar, that is because it is more or less the same one most colleges in the United States follow today).

Although there was mild internal resistance, most Harvard faculty supported this new modern system, even perhaps most surprisingly the Classicists. William W. Goodwin, the Eliot Chair of Greek, observed in his 1891 Phi Beta Kappa address, “The Present and Future of Harvard College” that “It is perfectly possible (though I sincerely hope it is not probable) that some whom we welcome here today for the first time have never studied a word of Greek or Latin…during their undergraduate course.” While he expressed some misgivings that a student might leave college without having read a line of Homer, he was overall pleased that this elective system would distinguish them sharply from the traditions of the European schools. It carried with it the additional bonus, to his mind, that students who were lazy, stupid, or uninterested in Latin or Greek would no longer clutter up those classrooms and drag the “better” students down.

Eliot’s goal, at least in part, was to abolish Greek and Latin as a normative part of American education, because in his eyes the peoples and ideas of the ancient Mediterranean were simplistic, outdated, and never helped anyone get a job: “As to the means of earning a livelihood for a family, no one will now think of maintaining that a knowledge of Latin would be to-day of direct advantage to an American artisan, farmer, operative, or clerk, inasmuch as the means of earning a livelihood in any part of the United States have been wholly changed since Latin became a dead language.” In his 1869 manifesto, “The New Education,” Eliot repeatedly marks Classical subjects as unfit for the modern student, and argues that the only education appropriate to an American child was an industrialized, utilitarian, career-focused one. The old Classics-centered general education produced only a pointlessly “rounded man, with all his faculties impartially developed,” and technical schools produced a “one-sided man,” a mere tradesperson. Eliot’s goal was a curriculum aimed directly at a student’s chosen profession as a means to create “commissioned officers of the army of industry.” Students could choose to study Greek or Latin, and to perform Classical plays if they wanted; these, however, were now merely pursuits of personal pleasure rather than necessities for a good life.

It wasn’t only schools in Europe that Harvard wanted to distance itself from, but also schools in the United States grounded in European traditions, especially Catholic Jesuit colleges. The Ratio Studiorum that formed the backbone of Jesuit education was a set core curriculum that dictated which subjects students studied in any given year. Unlike the curriculum of Eliot’s Harvard, which aimed to improve quality by sorting students into the subjects for which they were best equipped, the Jesuit Ratio was built on the premise that certain traditional fields of knowledge offered unique wisdom that no other field could supply and that the experience of all these, in a logical progression, was necessary to become whole. Its prime aim was to form every student, regardless of social or economic background, into a competent, virtuous, and well-rounded person through a unified course of study. But to Eliot, Harvard and the Protestant majority, the Ratio was an antiquated relic under whose direction graduates “could not properly be admitted even to the Junior Class of Harvard College.” In 1884, Eliot had asked, “Are our young men being educated for the work of the twentieth century or of the seventeenth?”

In her Catholic Higher Education in Protestant America: The Jesuits and Harvard in the Age of the University, Kathleen Mahoney documents how Harvard worked to cut the Jesuit colleges out of the educational landscape of the U.S., including by labeling their graduates as categorically unfit for admission to Harvard Law School (at the time, one of the surest paths towards upward social and economic mobility). The ensuing fight between Eliot and the Jesuits, especially then-president of Boston College, Fr. Timothy Brosnahan, riveted American higher education as they slugged it out publicly in the newspapers and magazines. Mahoney and others have shown that much of this debate was driven by virulent anti-Catholic sentiment in the period. Harvard viewed its traditional Protestant identity as a Christianity of liberation and its elective system as a tool to free the mind from old superstitions and outmoded thinking, while it saw set curricula in general and the Jesuits’ Ratio in particular as a closing of the mind. An earlier anonymous article in the Princeton Review sums up their opinion: “Protestantism is liberty—the liberty wherewith Christ has made us free. Popery is the yoke of bondage—spiritual despotism.”

This antipathy may help explain why half a century later, when Harvard had won and the Ratio Studiorum was all but dead, BC’s community was still nursing a theatrical grudge. Sophomore Leo F. Carty shared his thoughts on the value of different forms of Latin drama in no uncertain terms in the May 13, 1938 edition of the Boston College Heights: “In many non-Catholic schools, and in a few Catholic as well, the lewd comedies of Plautus and Terence were publicly exhibited by the students. To read Terence is dangerous, but to commit his works to memory, to become familiar with his persons and situations, and to perform all this, is truly moral suicide, especially in the case of youth.” By contrast, he calls Jesuit Latin plays a “beacon of light” and “safe path” because through them “the dramas [were] subordinated to religious and moral training.” He goes on: “The purpose of these plays was to stir pious emotions; guard youth against the evils of society; portray vice as intrinsically despicable; stir up a crusade of virtue; and strive for imitation of the Saints.”

Harvard and the other predominantly Protestant colleges touted the modern production of Plautus and Terence in Latin as true innovations pursued out of a passionate choice. They cast them as a uniquely American contribution to the arts that connected the plays directly to their Roman forebears. Young Boston College, by contrast, viewed neo-Latin Jesuit comedy as a way to strengthen its identity and to define itself as heir to a European tradition that had been suppressed but nevertheless remained unbroken. Both envisioned themselves as carrying on a form of the Classical tradition, each adapted to their respective goals. But in the end the Jesuit vision of the Classical curriculum was displaced, and BC and other Catholic schools had to adapt to the new system and to remake themselves in Harvard’s image, just as the Protestant schools had already done.

The question “Who produced the first Latin play in the United States?” is tiny, seemingly inconsequential. Still, it gives us a chance to examine a radically different set of values and goals than the ones that Classicists and American education today have inherited. If things had turned out otherwise, we might not be offering courses on Terence at all, but instead on neo-Latin drama, or at least the idea of what constitutes “Classical theater” might have included a more diverse and quirkier cast of characters. We might also be giving our students an entirely different set of skills that would prepare them for the future.

The Jesuit Ratio is likely too highly idiosyncratic and inarguably Eurocentric to justify its revival in anything like its original form, and Eliot was not wrong in pointing out some of its many flaws. But with its demise in the early 20th century, the United States lost a powerful alternative with an admirable goal: to educate the student as a whole person rather than as a living career. As educational theorist Cathy N. Davidson argues in her recent book, The New Education (an explicit call-back to the title of Eliot’s 1869 manifesto), the industrial age for which the profession-focused and utilitarian elective system was built is gasping its last breaths. We are in an increasingly precarious and mercurial age, and the current system’s shortcomings have become all too apparent. At this tumultuous moment, we would benefit from looking back to the educational models it displaced in the 19th century. These were models that asked not “What are you going to do with a degree in theater?” but rather “What kind of person can studying theater help you to become?”

Header image: Detail of a sarcophagus relief with the Muses and theatrical masks, from the Via Appia, Rome, Italy. Now in the Altes Museum, Berlin (Image by Carole Raddato via her Flickr Page under a CC-BY-SA 2.0).

Authors