This is Part 1 of a three-part series. Find Part 2 and Part 3 here.

Picture a student getting back a graded essay or exam. They glance at the letter or number at the top of the page and throw the paper in the recycling on their way out the door without reading the feedback, even when you think it will help them succeed on the next major assignment.

Imagine being consistently impressed by a student’s in-class work. Their insights and positive attitude contribute significantly to the learning environment. However, they do very poorly on the first major assessment, a midterm exam. Both of you are surprised and dismayed, and the student is discouraged.

Consider grading a batch of assignments. Looking at your rubric, you are struggling with the difference between an A– and a B+ for a few essays. You put them down to look at later.

The three of us decided to write this series of blog posts to share how our perception of assessing students’ learning has changed over time, after being faced with situations like the ones above. We have all felt, in various ways, that the methods we were using to understand student progress and evaluate them based on that progress were not fully adequate or effective — and, at the same time, were not helping to invite all students into our courses equitably.

In this post and two more to come, we will share how we have tried to improve both the student and instructor experience of assessment. These ideas are not “best practices” or things everyone should do, but approaches based in research on student learning that worked for us. We also need to acknowledge that our experiences using these strategies come from positions of racial and institutional privilege. Implementing new or different assessment strategies may have variable outcomes for instructors with diverse identities. Course planning is labor-intensive; flexible assessment policies can present special difficulty for instructors, especially contingent faculty, graduate students, and instructors from marginalized backgrounds. Instructors should prioritize their own mental health, prior experiences, and capacity when considering things like assessment plans.

We hope you enjoy, and we welcome questions and brainstorming!

What is Assessment?

What are assessments and why do we use them? In general, assessment is a collection of information about student learning that happens with and for students rather than to them. Assessments allow instructors to understand students’ progress; with meaningful feedback, they help students improve and achieve the goals of the course. Often, the word “assessment” seems merely to be a synonym for “grading.” Grades, however, only serve to evaluate student performance and do not always need to accompany assessments.

In practice, assessment design depends on the kind of information an instructor needs to gather. For example, activities as simple as checking in on students as they perform group work can function as assessment, especially when an instructor uses their observations to offer additional support to the class on topics presenting difficulty. Students can also be partners, in assessing both themselves and peers in formal (e.g., peer assessments, reflective essays, workshopping) and informal ways (e.g., think-pair-share exercises). Most of the in-class time we spend in language or other Classics classrooms helps us understand student learning and adjust our teaching accordingly, even if we don’t label all our interactions with students “assessment.”

The challenges of assessment and evaluation

Students sometimes focus primarily on the evaluative aspect of assessments: grades. This is understandable, because grades are often treated as a proxy for success or even intelligence; a letter or number is shorthand for how much a student has learned. Grades also have very real stakes for students who need a certain GPA to maintain a scholarship or apply competitively for graduate and professional programs or jobs.

However, grades do not necessarily represent student learning or progress accurately. A final grade often comprises a subset of grades, which sometimes include measures of student learning (e.g., grades on tests, quizzes, projects) and sometimes don’t (e.g., grades for attendance, participation). In fact, grades or other ratings systems, on their own, do not provide a way for students to reflect on their own learning or improve. Grades become more meaningful when we offer feedback in the form of observations (“I noticed you used the ablative case here”) and, when appropriate, advice (“I recommend looking at Chapter 3, which deals with uses of the accusative case, when working on test corrections. Please see me in office hours if you have questions”).

Both instructors and students may feel anxiety or even dread around grading. This dread can come from several sources, including progress/outcome mismatch, test anxiety, or simple exhaustion. When a student who performs well in class does poorly on a test, or when few students do well according to the standard set by the instructor, it may be a sign that the evaluation was not an effective measure of student learning.

Creating inclusive, aligned assessments

In Classics, students often have no prior learning in the discipline, especially in language courses. The amount of information that must be processed up front to be successful (especially if success means “receiving high grades”) presents a meaningful barrier to entry and can make initial assessments inequitable. Receiving a bad grade on a first Latin or Civ exam may feel like an overwhelming obstacle rather than the start of a learning journey, especially when that bad grade makes it impossible to receive higher than a B– in the class, for example. Put another way, the student who enters a class with significant prior learning and advanced writing skills is likely to write a good final essay, even if they don’t learn much new information. This discourages and pushes out students who have not had the advantages of elite high schools, private tutors, etc.

Similarly, for the student who has had those things, how meaningful is our teaching if they are able to achieve all our prearranged measures of success without significant input from us or their peers? What does the “A” that we assign demonstrate about their experience of and growth within the course? Instead of measuring a student’s growth, we may instead be signaling to the student with prior knowledge, “This class is for you,” while sending a message to other students that they “just aren’t good at this.” Early defeats in a class can send students packing or convince them that their efforts are better spent elsewhere.

If our goal as instructors is to encourage as many students as possible to engage authentically with learning from their own starting points, we must consider ways to help them focus on the formative potential of assessment rather than its evaluative force. Here are a few approaches we have tried based on the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Backwards course design

Backwards course design, a framework described by L. Dee Fink, recommends that course goals guide the selection of learning activities, assessments, and materials so that all aspects of the course are aligned, mutually interrelated components. The course goals in turn are informed by the circumstances, or situational factors, of the course (e.g., how advanced it is, enrollment numbers, curricular position, instructor comfort with topic, etc.).

In Latin or Greek classes, common goals may be increasing reading proficiency, analyzing the cultural context of ancient texts, or integrating prior learning with new grammatical concepts. Developing the skills needed to reach these goals requires practice and formative feedback. Consider: Does a traditional structure of 3–4 major exams supported by quizzes provide the most insight into student progress in those areas? Do we support students in practicing the skills needed to succeed on those assessments through learning activities and course materials?

In classes that depend heavily on group exercises for day-to-day learning, for example, students are learning collaboration and peer feedback as much as grammar. And, of course, as a classicist, it’s rare to work on a major piece of work (a new piece of scholarship or translation) without the aid of colleagues, dictionaries, and commentaries. Some alternative summative assessments might be group translation projects, portfolios of polished work, shorter weekly quizzes with no tests, formal test corrections, and more, depending on your students, course context, and goals. You may even switch to an assessment plan that leverages only formative assessment. The options are many.

When designing a new course, then, consider starting with goals for the class. Fink recommends asking what you would like students to remember several years after being in the course. Which assessments will help students achieve that learning? You can also ask students to articulate their goals to you to guide how you spend class time and assess them.

Reconsidering your course context

As we said above, how you design your assessments depends on your course’s situational factors and goals. Here are some of our favorite resources for brainstorming and creating meaningful assessments.

- Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT), an evidence-based framework for assessment design

- Strategies for metacognitive support to refocus students on learning rather than grades

- Carnegie Mellon’s Eberly Center for Teaching and Learning resource on creating exams

- Recent research on assessment: one of our favorite resources is MSU’s Online Language Teaching page (lots of great tips for the classroom, too)

What can you do?

Whether or not you decide to give alternative assessment a try (see our upcoming posts!), we have found that building in numerous formative assessments and making sure that our assessments align with our learning goals have brought many benefits. It has created greater equity in our classes and has reduced anxiety in the students and in us as teachers. Moreover, students feel encouraged and supported. And the more students who decide that the Latin class or the ancient history class that they were apprehensive about is a place where they can succeed — well, that is good for all of us.

- Take time to think critically about how you are evaluating students and consider whether those evaluations are helping students reach your goals and theirs. Consider journaling about your current teaching or even just jotting down some ideas over your next morning coffee. You can also ask your students how they are benefiting from assessments with some form of midterm student feedback.

- Make an approachable change that fits your course context. We will offer some alternative styles of assessment in the following posts. If those sound too extreme, consider making just one change: how could you rephrase or repurpose even a single assignment?

- Check out a scholarly book, article, or podcast on evidence-based assessment. We find them helpful for planning and recommend Carnegie Mellon’s scholarship of teaching and learning monthly digest. Dead Ideas in Teaching and Learning is a great place to get new ideas. Although it is geared to K-12 educators, we also find The Cult of Pedagogy podcast to be helpful.

- Talk to someone about your teaching! Reach out to a friend, colleague, or your local teaching center to discuss ideas. Teaching is hard, and finding a community of practice can be a great support.

- Check out our webpage, where we have collected some of our favorite resources.

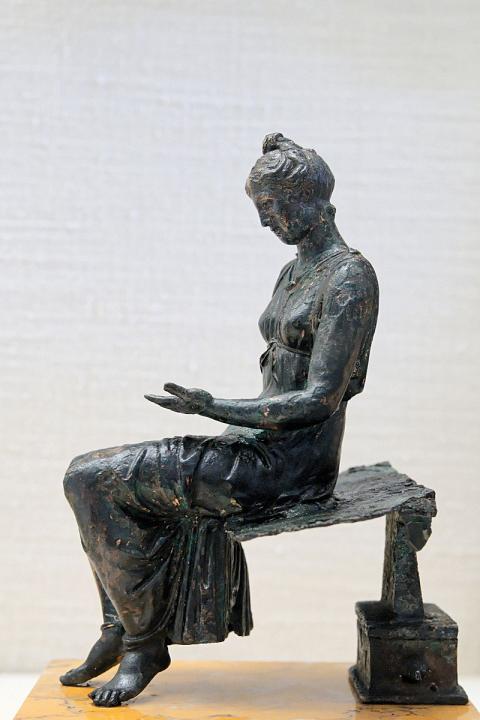

Header image: Bronze statuette of a girl reading, possibly 1st c. CE. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.