Adrienne Rose

September 27, 2018

This month in her ‘art of translation’ column, Adrienne K.H. Rose interviews A.E. Stallings while in Pylos and then in Virginia. The two discuss the word choices made by translators, the surprising relevance of Archaic poetry in the tumultuous present era, and the effects of living life in a foreign language.

Q: How did you decide to study Classics?

Gradually, then suddenly—I didn't start taking Latin until college [at the University of Georgia], where I was initially an English and Music major, but I started with Latin 1, and just kept taking more and more Latin and Classics courses until finally the department (in particular Rick LaFleur, then Dept. head), gently suggested I change majors.

Q: Could you say a bit about the significance of learning Latin and Greek and translating Classics and its impact on you?

It changed my understanding of writing poetry for one thing. As I've said elsewhere, I realized how contemporary Catullus sounded, but also that he was writing in very strict poetic forms. I realized you could sound modern and scan. I realized that ancient poets often sounded more up-to-date to me than a lot of what I was reading in contemporary literary journals. It removed some anxiety I had about the modern literary scene.

Q: In the process of translating Hesiod’s Works and Days, what challenges in translation did you encounter and how did you work around them? Could you give one or two examples?

Putting the hexameters into iambic pentameter sometimes meant having very little wiggle room--I sometimes dropped an epithet, for instance, that didn't seem to do much in the Greek other than fill out the metrical line. One example is:μερόπων ἀνθρώπων—“meropon” meaning “having a share in speech.”

It really just boils down to humanity—anthropoids who have language, homo eloquens. I decided that “humanity” encompassed the epithet. Another case was χρήματα, possessions or goods, the needful things, which is, in modern Greek (and later Classical Greek) “money”—yet money per se probably was just getting invented or about to be invented over in Lydia. Hesiod seems to be talking about “money” in some places somewhat in our sense of it—as in the Biblical “love of money is the root of all evil.” I have Hesiod saying “Money's the breath of life for poor mankind” and I think readers will understand what I mean. But I do have a footnote about it. These are very specific examples I realize.

Q: In your translator’s note to Hesiod’s Works and Days, you draw several striking parallels between Greece in the 8-7th c. BCE and 21st c. CE, from vocabulary and harvesting seasons to inheritance disputes, austerity, and immigration. What can readers learn from Hesiod’s Archaic Greece in terms of approaching contemporary issues?

I was surprised to find Hesiod so topical. His concerns—debt, work, justice, corruption—are very much contemporary concerns. Many of us feel we are living in a dark time, an iron age. It is helpful I think to realize people have felt things were going to hell in a handbasket even in archaic times. We are not the first. Hesiod's sensitivity to the earth and seasons, to the natural world around him, also has an urgency. His concern was the change of seasons, and ours with changes to our climate, but in both cases observation of and respect for the natural world are of critical import.

Q: Living your life in a foreign language includes a certain degree of living life in translation, I imagine, considering the ‘other’ and seeing yourself as ‘other.’ Could you say a bit about how living abroad and learning a foreign language has shaped you and your writing?

I think the effects of living life in a foreign language are twofold. One is that you have other metaphors and etymologies available, other connections between words and concepts. The word for entertainment/amusement in Greek is psychagogia—something that leads the soul. When the rain comes pouring down, it doesn't rain cats and dogs, but chair legs.

Everything is gendered. A fox, whether a tom fox or a vixen, is always feminine. You also have a whole other poetic tradition available to you. Poetry is embedded in Greek in ways it doesn't seem to be so much in English. There is a huge tradition of turning poems into popular song, for instance. Politicians regularly quote Cavafy or Seferis.

The flip side is that you need to be careful about not losing your feel for vernacular English. My kids, who are native English speakers as well as native Greek speakers, still say some odd things in English like to “close” or “open” the lights, which they’ve imported from Greek.

Q: How did you get connected with the Melissa Network?

I started workshops at Melissa in 2016, at the suggesting of Nadina Christopoulou at Melissa. Originally, these workshops were for migrant women more generally (mostly women from Albania and Nigeria and the Philippines) who were working, often as domestics, in Greek households. I am an immigrant here myself, though my reasons for coming here are different and I came under easier circumstances; but I do have an inkling of what it is like to live life in a foreign language, at the least.

As the refugee crisis burgeoned, and as it became more visible in Athens, Melissa also shifted and expanded its mission to the integration of refugee women, so it seemed natural to shift our focus too. (The poetry program is now part of a larger grant that will, at the end, involve a documentary film.) My husband is a journalist who had done some interviews with women through Melissa, and Melissa network was aware that I was a poet here in Athens with an interest in migration issues, so I think that's how they found me, and also why we connected.

Q: Could you describe the poetry workshop you run with the participants there?

The women vary in age from 16 to 35 (or older), come from different countries (Iran, Iraq, Somalia, Congo, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria) and speak different languages. Usually our class is mostly Persian/Farsi speakers (with some Dari dialect), and a smaller but very focused contingent of Arabic speakers. We have translators for Persian and Arabic who are themselves immigrants and sometimes participate in the exercises. Women sometimes write in their native tongue, and translate it into English via dictionaries on their phones, or with help from each other or a translator. I usually give a prompt--it could be to write about a certain kind of memory, or imagine yourself as a kite, or an acrostic poem with the letters of your name, or pick an image from a post card and write about it.

It is vastly different from most classes in creative writing I have taught. They might struggle with English, or this might be the first time they have written anything creative (they may not even have had much in the way of formal schooling), but they embrace the idea of playing with language, and writing about their own feelings and experiences in the first person can be transformative for them. They have also been through so much, there is so much emotion and experience and sorrow and joy and endurance and hope and terror and resilience and strength--few words are wasted and everyone has a lot to say. And of course they often come out of cultures and traditions where poetry is central and revered.

Q: Please share three recent books from your reading list that you’ve enjoyed.

I've enjoyed Emily Wilson's new Odyssey, Jaroslav Kalfor's Spaceman of Bohemia, Border: A journey to the Edge of Europe by Kapka Kassabova, and Helen Macdonald's H is for Hawk. I'm looking forward to reading the new Circe novel.

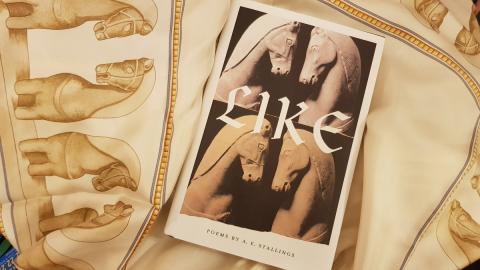

Q: Your next book of poetry, Like, is scheduled for publication on September 25. What future projects are you most excited about?

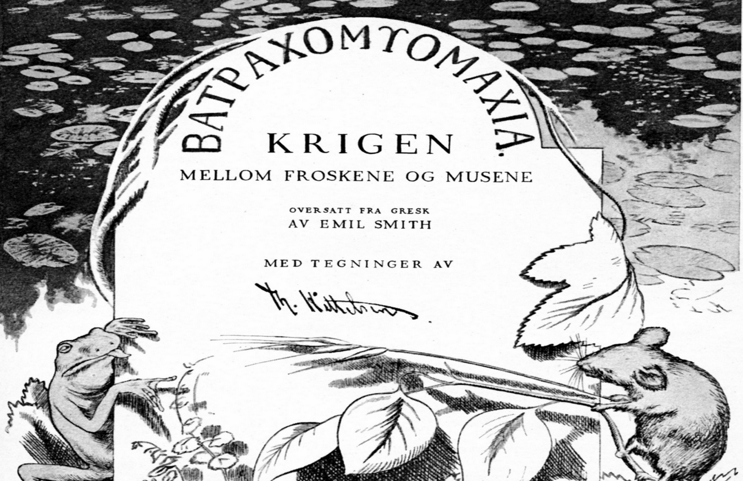

I have a Battle of the Frogs and Mice coming out with illustrations! I just need to finish the introduction.

A.E. Stallings is a translator and poet who lives in Athens, Greece.

Header Image: Image of A.E. Stalling’s new book of poetry, Like, and a scarf with its cover printed on it (Image used by permission and taken by John Psaropoulos).

Authors