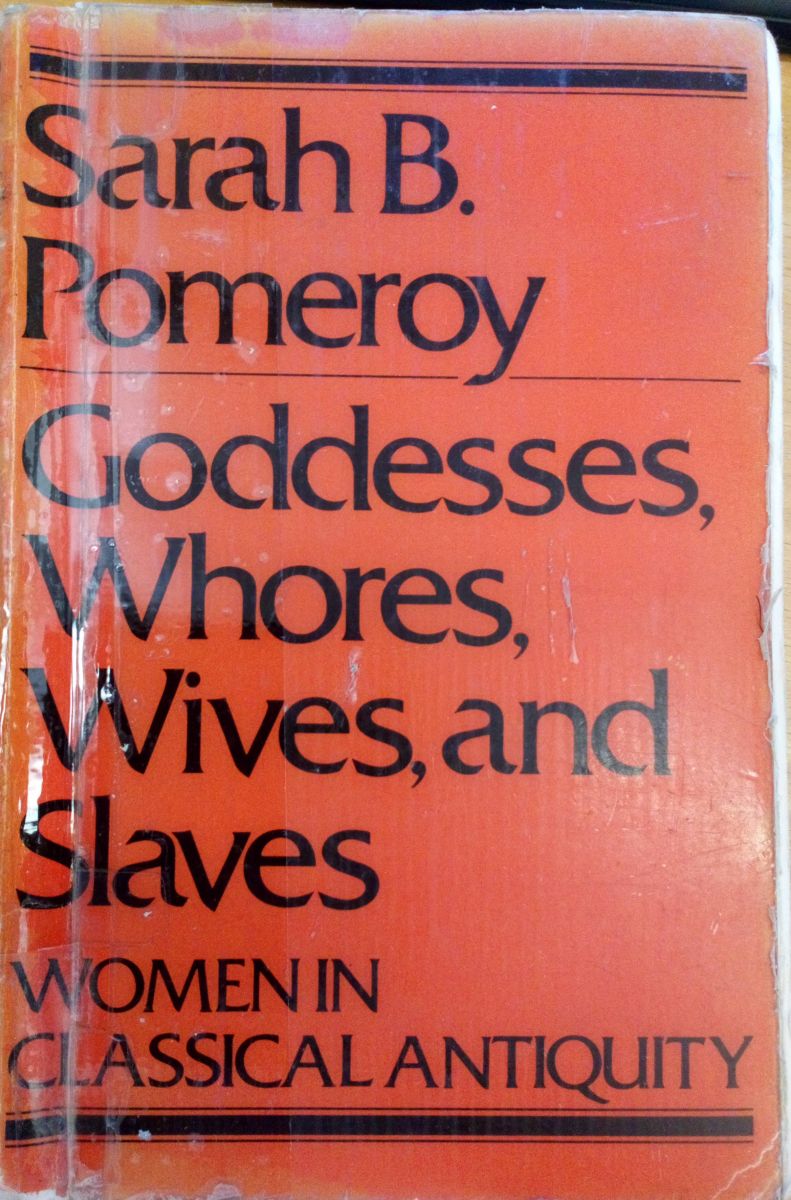

Our first interview in the Women in Classics series is with Sarah B. Pomeroy, Distinguished Professor of Classics and History, Emerita, at Hunter College and the Graduate School of the City University of New York. She was born in New York City and earned her B.A. from Barnard College in 1957. She received her M.A. in 1959 and her Ph.D. in 1961, both from Columbia University. Pomeroy has been recognized as a leading authority on ancient Greek and Roman women since her book Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity was first published in 1975. Her other publications include Xenophon, Oeconomicus: A Social and Historical Commentary (1994), Families in Classical and Hellenistic Greece: Representations and Realities (1998), Spartan Women (2002), and, with Stanley M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts, the textbooks Ancient Greece: a Political, Social, and Cultural History (4th edition, 2017) and A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society, and Culture (3rd edition, 2011).[i]

Image used by permission of Prof. Pomeroy.

CC: How did you come to Classics?

SP: When I was a teenager, I lived with my parents on Fifth Avenue and 78th Street, so it was natural for me to spend quite a lot of time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was different back then. It did not have the grand staircase that it has now in front, and it was never crowded. One could go in there and be quite alone. The halls were cool and dark. I liked to wander among the mummies on the first floor. There were two huge Etruscan sculptures in the main hall. Later it was discovered that they were not genuine, but they were gorgeous anyway, and they had been copied from small Etruscan originals. I loved those sculptures. I attended the Birch Wathen School, which was on the West Side back then. Everyone took French. I also took Latin and ancient history. About a third of my class—my class was only 43 people—went on and got PhDs. Not only in Classics, of course, but mostly in humanities fields. It was a great school.

I was sixteen when I graduated from high school, and then I went on to Barnard and I took Classical languages there. The department at Barnard was very small. It was just one person, John Day, who later became my dissertation advisor. He was a papyrologist. Because Barnard was so small, I ended up taking most of my classes at Columbia. The undergraduate courses were in Hamilton Hall, but back then women were not allowed into Hamilton Hall before twelve o’clock noon. This was because the big humanities courses, taught by Van Doren and other famous professors, were held there in the morning. No woman could ever take those classes. But the Classics courses were held in the afternoon, and they were undersubscribed, so they let Barnard students take them.

CC: What was your family culture like around Classics?

SP: My mother had gone to Hunter College, but no one else in the family knew Greek or Latin.

CC: Tell me more about Barnard when you were there as an undergraduate.

SP: I went through college in three years. I graduated when I was nineteen, in 1957. Barnard was very much a women’s college in those days. There weren’t many men around. As I said, I took some of my courses at Columbia, and I went through the curriculum so quickly that I ended up taking graduate courses when I was still an undergraduate. When I graduated, all my friends were still in college, of course, so I just continued to take courses in the Classics program at Columbia. Because I had already taken most of the required courses in literature, I was able to fill my program with ancient history, art history, and Greek philosophy. I studied with Otto Brendel and Eve Harrison. I think this helped me in my eventual study of women, because I realized that if you were just going to be a philologist and depend on the famous texts, you’d never find out enough about women to write even one book. I also trained in papyrology with John Day. John Day had been a student of Rostovtzeff, the great historian who praised Altertumswissenschaft, using not just texts, but all kinds of information about the ancient world. It was revolutionary, in those days, to have photographs in a Classics book. But that’s how I was trained.

I did my dissertation on one ancient document, a lease for an olive grove. This lease had three new agricultural words. I had to work out what they meant, and they went into the next edition of Liddell and Scott. The papyrus was full of worm holes and abrasions, and written in a kind of everyday Greek that you would never find a textbook.

CC: What was so exciting about the lease for this olive grove?

SP: Despite the prevalence of olive culture in the ancient world, this was the first lease of an olive grove that had been published. The grove was in Karanis in Egypt, and the lease was in the Roman period. I was interested in the document because of the new agricultural vocabulary, but in fact one of the partners to the lease was a woman. In those days, it didn’t even strike me that this would be something worth studying, a woman as a signatory for a legal document, a woman as a proprietor of a lucrative olive grove. Nobody asked me about the woman signatory at my dissertation defense. It wasn’t of interest to anybody in those days. There were no women on the faculty at Columbia in Classics. Of course there was Eve Harrison in the Art History department, but no one in Classics.

CC: Tell me about your first job.

SP: I was young. When I finished my PhD, my friends were just graduating from college. I was already married, and my husband owed two years to the Air Force, because he had been deferred. So we found ourselves in San Antonio, and I got my first teaching job at the University of Texas in Austin. I was the only woman in a department of twelve. That was an interesting department. A lot of people became famous: William Arrowsmith, John Sullivan, Jim Wiseman. Jim founded the first chapter of the AIA in Austin, and I was a charter member. The chair in Austin was Harry Leon, who had written The Jews of Ancient Rome. His wife Ernestine had a PhD as well, but there was a rule against nepotism, so she was not allowed to teach. She was stuck there in Austin. I think she managed some correspondence courses. But all this didn’t add up for me. I didn’t really see the whole picture for a while.

CC: When did you start to see the whole picture?

SP: I remember that the men in the department, around 11 o’ clock, would say to each other, “Come, let’s go out for coffee.” They never invited me. I thought it was because I was the youngest person there, and they had all been friends for a while. I didn’t like it, but it didn’t occur to me that it was because I was a woman. I liked being in Texas. I learned to fly; I bought my own plane. I used to like to fly down to the Gulf and fly low, so that the spray would hit my windshield. I just loved it. But then, after my husband had done those two years, we came back to New York in 1964. I fell into the clutches of the City University of New York, and that’s what taught me to be a feminist.

CC: Tell me about working at the City University of New York.

SP: First of all, Hunter hired me as a Lecturer, which was a rank for people without a PhD. They hired me one step below where I should have been hired. At the time it didn’t even occur to me that this was incorrect, because I was just so pleased to get a job in the city near my husband. I was offered other jobs, but I had a young family, and I didn’t want to commute. While I was at Hunter, I had two more children. I found out that there was a maternity law on the books, and no one – not a student, not a faculty member – who was pregnant could begin a new semester. You could just finish out your semester, but you couldn’t start working again until the pregnancy was over. And then there was another rule on the books: you needed to work for five successive years to get tenure. So each time I had a child, I’d go back to year one, like Chutes and Ladders. It took me fifteen years to get tenure, and I never got the backpay, the promotions, and the fringe benefits, for all those years.

I was not the only woman in this situation, obviously. So in 1973 the women of CUNY mounted the largest class action in America up to that time. The suit was not handled by the Union, because the people in charge of the Union were men, and they were not interested. There was a woman named Lilia Melani at Brooklyn College who formed the CUNY Women’s Coalition, and she managed this huge case. I was one of the twelve named plaintiffs. Judith Vladeck was the lawyer. We won the case. Every woman who had ever applied for a job, been fired, or been hired, each got $300. Can you believe that? But we had the satisfaction of having the maternity law revoked.

CC: Would you say that you became a feminist because of the CUNY Women’s Coalition?

SP: Because of my treatment at Hunter, yes. I was also very friendly with feminist historians, and I was a member of the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians. When I was on the program committee, every time slot was filled with Classics papers. Many women were beginning to study women in antiquity. But I was the first. My book Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity came out in 1975. It’s still in print. We had a little group in New York: Froma Zeitlin, Marilyn Arthur, Leona Asher, and Grace Muscarella. We would meet occasionally and talk about teaching courses on women in antiquity.

Wives, and Slaves (1975). Image via Wikimedia, CC By-SA 4.0.

CC: How did you come to write Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves?

SP: I just asked myself, “What were the women doing, when the men were doing everything else that we were studying?” When that book came out, it was immediately reviewed in very public places, like the New York Review of Books, and TLS, and the New York Times. There were also scholarly reviews, of course, and foreign translations.

CC: Many of the women whom I’ve spoken to cite your book as an important moment in their own development as scholars. They say there was no bibliography to teach a course on women in antiquity course until your book came out in 1975, and then suddenly there was an actual, scholarly text to work with.

SP: I taught the first course in America on women in antiquity. Actually, the course was on women and slaves. I published the syllabus for the course in Arethusa so other people could use it. Then I got a big grant from the NEH to organize two summer institutes on the teaching of women in antiquity. A lot of people were in that group, including Helene Foley, Amy Richlin, and Barbara McManus.

CC: How did students respond to this new material?

SP: The course was always well-enrolled at Hunter. There were a lot of students who were interested in it, mostly women. Hunter was a women’s college originally, but after the Civil Rights Movement, CUNY made all colleges coed: City College had to take women, and Hunter had to take men. But we never had many men. Hunter remained 80% women, because there wasn’t a football field. The whole campus is just three buildings. The way I developed my Women in Antiquity course relied on slides, which was rare in those days. But so much of the information about women comes from material culture, not from texts. For instance, when I wrote about the literacy of women in one of my articles, my prime evidence was terracotta figurines of little girls with papyrus rolls. That methodology goes back to Rostovtzeff, to the way I was trained in Altertumswissenschaft.

CC: How do you think that the field has changed for women since the law court case at CUNY and the arrival of feminism?

SP: You would know better than I do, because you’re living it. We formed the Women’s Classical Caucus in 1972, which ushered in a lot of changes. Bill Willis, who was the president of what was then the APA, gave us funding, grudgingly. He said he was thinking about his two daughters. But then Harry Levy, the next president, said, “Why should we fund you? You’re an antagonistic group. You’re antagonistic to the APA.” So we had to fend for ourselves. The APA was an old-boys’ network in those days. One group of officers would choose the next group, and there never were any contested elections. But eventually the APA formed their own women’s committee, and that committee published a questionnaire which showed all kinds of discrimination.

CC: In what ways do you think that the field excluded women in the 1970’s?

SP: Jobs, certainly. A friend said that when she was a graduate student at Harvard, she went to the professor who was in charge of placement, and this professor had a huge stack of listings and a small stack of listings. The huge stack was for the men, and the small stack was for the women. I don’t think that’s still the case for your generation; again, you would know better than I.

CC: What I’ve noticed is that many people are reluctant to talk about the way the field worked in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Consequently, there is a lot of ignorance among women of my own generation about the history of the discipline.

SP: While I was at Hunter I also started working on my textbook for Greek history. When I first was recruited to teach Greek history, I looked around for a textbook, and there was nothing that I thought would suit my students at Hunter. Most of the textbooks were British. They were old, and they didn’t have maps, and they didn’t have photographs. There was nothing appealing about that. So I recruited a few colleagues—my friends Stan Burstein, Jenny Roberts, and Walter Donlan—and put together a proposal for Oxford University Press. A young editor there, Robert Miller, who now is at the top of the editorial staff, worked very hard on the book with us. He even worked weekends. He chose beautiful covers: artistic photographs taken by Eliot Porter, which are now in the Amos Carter Museum.

But I have to go back a little. Before the Greek history textbook, I organized the first interdisciplinary textbook in Women’s Studies. I got a big NEH grant for doing that. For the first edition, we had something like ten authors. I used a system that I had developed in the NEH summer seminars on women in antiquity. This textbook was written by scholars from many different disciplines who were interested in women’s studies. But I didn’t want to divide the book up into disciplines. So I came up with a series of concentric circles starting with the woman, and then her roles: daughter, sister, mother. We also looked at women’s place in society, religion, and the economy. Every chapter was written by more than one person. And then when the page proofs came back, a third and a fourth author read them. If you’ve done a book, you know that you get kind of glazed. You don’t notice your own mistakes. But having a new set of eyes picks up errors, as well as material that shouldn’t be in a textbook, or things that are not clear for students. That women’s studies textbook has gone on to the fourth edition.

CC: In several of your projects, I see common themes of interdisciplinarity and collaboration. Do you think that there’s something about these methods that is particularly the province of female scholars?

SP: Other people do it, but I think it’s unusual to organize a textbook to be written in this kind of round-robin way. But I insisted on it. I said, “This is the way we work. Nobody owns a chapter.” That way you get more minds on the same thing. It’s especially good for a textbook, because you don’t want any one person to go off on a tangent. You want some kind of consensus. Why should the student learn something eccentric?

That textbook changed the teaching of Greek history. With the textbook, I think I may have had a bigger impact than with any of my individual monographs. Because some professors—I would probably think male professors— would not ever look at a book that had the word “women” explicitly in the title. But they used our textbook for history, because it was obviously the best. And so they ended up teaching women in antiquity in spite of themselves! The original book did so well that we did a second smaller version, and that one is the largest-selling English-language Greek history textbook in the world.

CC: As an undergraduate I learned from your textbook.

SP: In that book, I made sure that there was a lot on women, but it’s in there in a natural way. There’s not a separate chapter on women, because then some professor might say, “You can skip that chapter, it’s not important.” Instead women are in there wherever they’re supposed to be, and slaves as well. So I changed the teaching of Greek history. We got away from wars and great men and generals, too. We added social history. We still included wars, because some people like to read about them, and they are important, after all. When I was elected to the American Philosophical Society, which is a great honor, one of the people on the nominating committee said, “The reason you were elected is that you changed the paradigm.” He said no one would dare teach Greek history the way it was taught before my textbook. And recently Random House reissued Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves. All of my books are still in print. When Random House put out the latest edition, the editor said, “This is one of the five paradigm-changing books of the 20th century.”

CC: What professional challenges remain for women?

SP: I think women have made great strides, both in Classics and in Archaeology. I’ve been a member of the AIA since I started out at the University of Texas, and I’m still very excited about it, because there’s always something new in the American Journal of Archeology. It’s not just re-analyzing some tiny poem of Martial, but there’s really something new, a new discovery.

CC: What advice would you give to your former self?

SP: I wish I had been more alert. I wish I hadn’t taken all of the discrimination I took without fighting back for so long. But I had a full life; I had three children, I had two houses, I had a lot of things to balance while I was teaching and publishing.

CC: What are you working on that excites you?

S: Well actually, my most recent book is not in Classics. I wanted to write a book for my seven grandchildren. It started off as a private book about Maria Sibylla Merian, who studied the metamorphosis of butterflies in the late 1600’s. Then my daughter, who was working at the National Museum for Women in the Arts, got the Getty interested in publishing it. They publish two children’s books a year. Maria Sibylla was a scientist and a pioneer and an artist. She went to Suriname, and painted insects that no European had ever seen before. Her paintings became biological specimens for Carl Linnaeus. He trusted that her details were correct, so that when he didn’t have a living or dead specimen of an insect, he used her paintings to classify different species.

CC: What a beautiful book! It follows your characteristic methodology of incorporating visual evidence, documentary evidence in the form of quotations, sidebars on history and science, and then your own narration. What do you hope your grandchildren will learn from this book?

SP: My grandchildren helped me write it. The ones who were the right age, between ten and thirteen, read the manuscript. I asked them, “Are there any words you don’t understand?” My grandson, who was twelve at the time, said “Protestant, what does that mean?”

CC: Do you think that Classics will survive and even thrive as a discipline?

SP: Oh, yes. There’s always been an audience for Classics, and there always will be. Of course the audience changes. When I first taught at Hunter, the majority of students in the Greek and Latin classes were girls from parochial high schools. They were still wearing their plaid uniforms, because they weren’t wealthy, and why throw out good clothes? And there were some who never made a mistake. Not even in an accent mark. Not all of them were brilliant, but they knew how to study. Now there are different audiences, such as retired people who want to go back to school. There will always be people who want to learn about the Classics.

[i] For further discussion of Pomeroy’s career, see Ronnie Ancona’s “Introduction” to New Directions in the Study of Women in Antiquity, edited by Ronnie Ancona and Georgia Tsouvala, forthcoming from Oxford University Press.

Header Image: Terracotta kylix (drinking cup) ca. 470 B.C. Attributed to the Villa Giulia Painter. Image via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0 1.0.