At last year’s SCS annual meeting in Boston, the Program Committee sponsored a panel called “Rhetoric: Then and Now.” Among the speakers constituting that panel was Princeton University Professor Dan-el Padilla Peralta, who, in lamenting the “inadequacy” and “meagerness” of a number of recent efforts in the field to diversify and expand access, delivered the following provocation: “perhaps it is time for this contemporary configuration of Classics to die so that it might be born into a new life.”

In response to Padilla Peralta’s provocation, I cheekily stood up and asked him where Classics ought to die and where it ought to live. (Full disclosure: Padilla Peralta and I are good friends from graduate school.) I asked this question because, living and working in flyover country—in the state of Nebraska—I can say that Classics here (and in the Midwestern states that surround me) is already dying. More often than not, where it lives is through symbiosis with another academic department.

(Photo via the Library of Congress, Civil War Photograph Album).

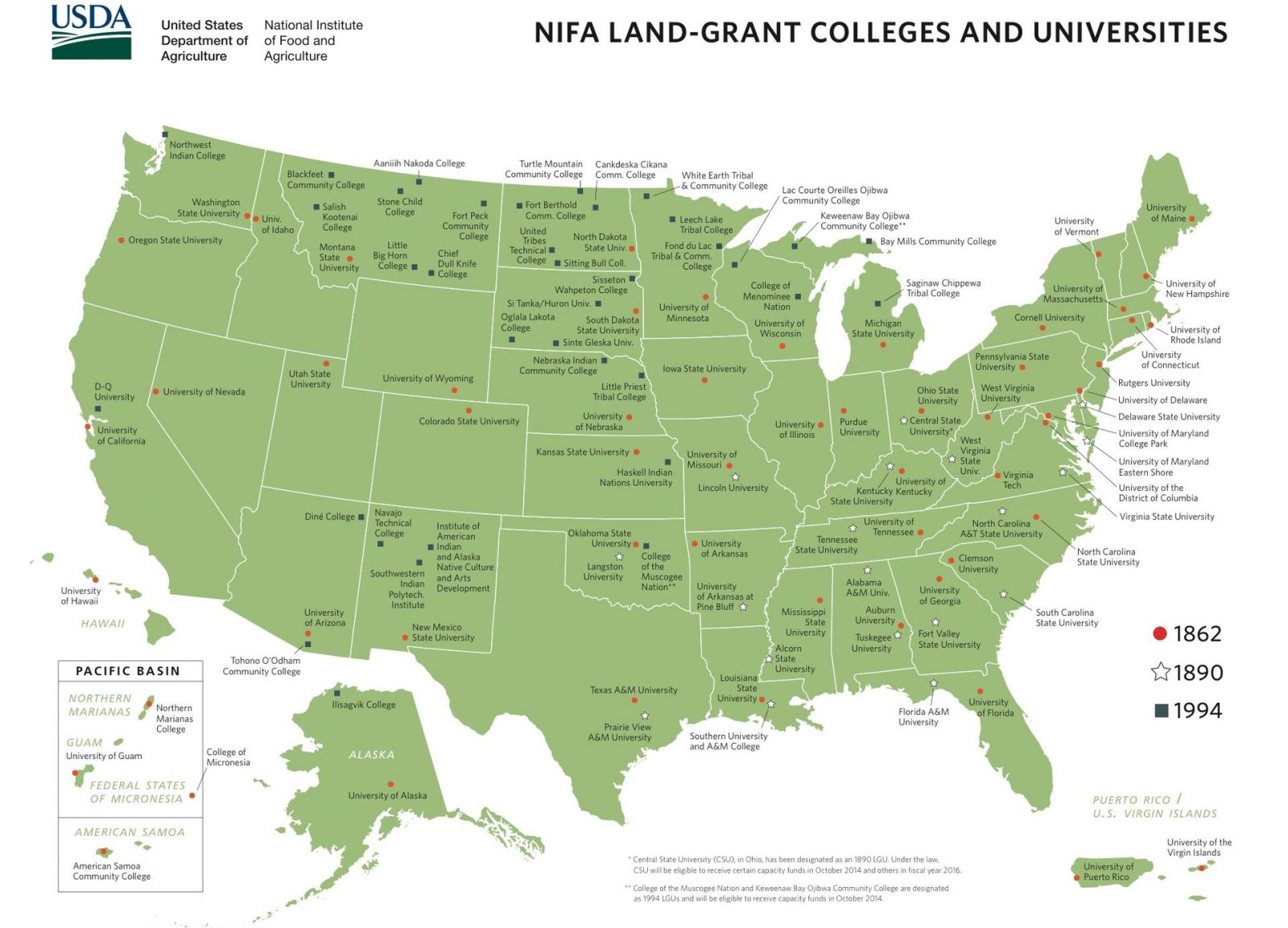

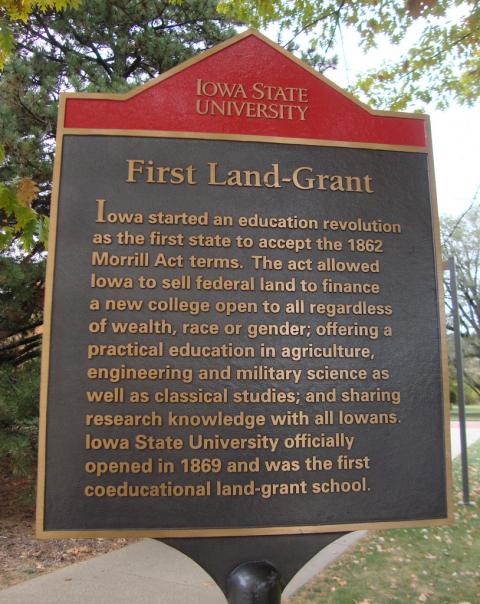

Particularly at state universities, the slow death of Classics in middle America is all the more striking given the origins of most of these universities as land-grant colleges created by the Morrill Act of 1862. Passed in the midst of the American Civil War, the act permitted states to direct the income derived from the sale of federal lands toward the creation of land grant colleges.

In addition to setting the appropriate sale price of acreage and prescribing how the money earned from those sales was to be invested, the Morrill Act also stipulated the educational outlets to which those funds could be put. Section 304 of the law enumerates which educational programs these land-grant colleges are intended to provide. It is instructive to see how the framers of this statute envisioned the new educational model their law was designed to facilitate:

Provided, That the moneys so invested or loaned shall constitute a perpetual fund…to the endowment, support, and maintenance of at least one college where the leading object shall be, without excluding other scientific and classical studies and including military tactics, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, in such manner as the legislatures of the States may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.

The founding charter of my employer, the University of Nebraska, reflects the stipulations of the Morrill Act. In Section 8 of the charter, which lists the colleges and chairs to be established at the founding of the university, classical studies indeed receives pride of place:

Sec. 8. There shall be established in the several Departments in the last Section named, to wit:

1st. For the College of Ancient and Modern Literature, Mathematics and the Natural Sciences:–

a. Two chairs of Ancient Languages

b. Two chairs of Modern Languages

Today, we are lucky. The University of Nebraska–Lincoln (founded, like the APA/SCS, in 1869) has a Classics and Religious Studies department that offers a joint major in Classics and Religious Studies and, for at least another nine months, a separate major in Classical Languages. As of 2017, we are the only college or university in the state that offers a major in Classics or Classical Languages.

Our neighboring land-grant institutions have not been so lucky. Research on the websites of the following universities that were created and/or given land-grant status by the 1862 Morrill Act reveals a worrying trend among land-grant colleges and universities in flyover country: some do not even offer Latin or Greek, few offer majors in Classics or Greek and Latin, and fewer still have standalone departments of Classics.

- Kansas State University (1863) was the first university created as a land-grant institution, and today its Classics curriculum is delivered by a single faculty member in the Department of Modern Languages.

- Iowa State University (founded in 1858 and designated as land-grant in 1864), was the first college to accept the terms of the Morrill Act of 1862; it happily still offers a major in Classical Studies through its Department of World Languages and Cultures

- The University of Missouri (founded in 1839 and granted land-grant college status in 1870) witnessed a consolidation of its Department of Art History and Archaeology and Department of Classics into a new Department of Ancient Mediterranean Studies in 2017, but its interdisciplinary graduate program was saved in 2018.

- Colorado State University (1870), the land-grant university of Colorado, offers courses in Latin but no minor or major through its Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures

- South Dakota State University (1881) offers neither Greek nor Latin

- The University of Wyoming (1886) houses Classics in its Department of Modern and Classical Languages, but it has only one faculty member covering its Classical language courses, which contribute to minors (but not majors) in Classical Civilizations or Latin.

All this returns me to Prof. Padilla Peralta’s original provocation, namely that Classics in its current iteration needs to die and then to be reborn if it will survive. In middle America, at least, this means Classics needs to reinvent itself unapologetically as a discipline that can help students hone the practical skills necessary to land employment. The argument that Classics makes good citizens, or that it makes students better thinkers, simply doesn’t hold water with a lot of my students; they need to be able to point to deliverables, and we need to help them see them.

How can we do this? Planned events, public facing digital humanities projects, and social media are all places to start. Large-scale events like Homerathons can both celebrate Homer and help students develop leadership, communication, and organizational skills. Digital humanities research projects can both give students traditional research experience and train them in new methods of publication and information analysis. Even hiring students to run departmental social media accounts—hunting down op-eds about the value of a liberal arts education, for example—both provides them an outlet for publicizing their love of the discipline and teaches them about public relations and media literacy. We don’t need to overhaul the curriculum, but we do need to find ways to bridge the gap between the classroom and the working world.

The Morrill Act, after all, demands that education at land-grant institutions be steeped in both the liberal AND the practical.

On Saturday, January 5, 2019 (10:45-12:45) at the annual meeting in San Diego, we will be discussing and debating the future of Classics as a field at the Special 150th Panel "The Future of Classics" (Sesquicentennial Workshop, organized by Stephen Hinds, UW-Seattle). To see the preliminary schedule for the meeting, click here.

Header Image: Morrill Act, taken April 12, 2006. Image via Flickr by roosac under CC-BY-2.0.