T. H. M. Gellar-Goad

September 25, 2014

In July’s column, I drew out some thematic similarities between the January 2014 movie The Legendary Hercules starring Kellan Lutz and the July 2014 movie Hercules (henceforth “Rockules”) starring Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. In this month’s column, I discuss Rockules as an adaptation of Steve Moore’s Hercules: The Thracian Wars comic books.

In Rockules, the climactic scene — in which Hercules, chained to two pillars, breaks free while screaming “I am Hercules!” — is taken almost directly from the Steve Moore-authored Radical Comics miniseries of which the film is an adaptation. It’s a reasonably close, though not rigorous, adaptation, and some of the divergences from the comics work in the movie’s favor by making for a smoother narrative and richer characterization. (Steve Moore died this March, and his longtime friend and fellow comic-book author Alan Moore has called for a boycott of the movie on the grounds that the adaptation is too unfaithful and that Steve Moore was not paid royalties he was supposed to receive; Alan Moore isn’t generally a reliable source for comic-industry dealings, however, and in making the call for the boycott he also made misstatements about the Hercules comics themselves that suggest his unfamiliarity with both them and the myths on which they’re based…)

In Rockules, the climactic scene — in which Hercules, chained to two pillars, breaks free while screaming “I am Hercules!” — is taken almost directly from the Steve Moore-authored Radical Comics miniseries of which the film is an adaptation. It’s a reasonably close, though not rigorous, adaptation, and some of the divergences from the comics work in the movie’s favor by making for a smoother narrative and richer characterization. (Steve Moore died this March, and his longtime friend and fellow comic-book author Alan Moore has called for a boycott of the movie on the grounds that the adaptation is too unfaithful and that Steve Moore was not paid royalties he was supposed to receive; Alan Moore isn’t generally a reliable source for comic-industry dealings, however, and in making the call for the boycott he also made misstatements about the Hercules comics themselves that suggest his unfamiliarity with both them and the myths on which they’re based…)

The movie’s foremost divergence from the source-material, however, is that it cleanses the comic books for a more anodyne, familiar product for cinematic audiences.

One of the objects of this cleansing is dangerous sexuality. In Steve Moore’s comics, Hercules’ fellow-warrior Atalanta chooses women as her sexual partners and continually fends off the affection of their comrade Meleager; in the movie, Meleager is absent and Atalanta has no express sexuality beyond a brief penis joke directed at her companion Autolycus. In the books, the Thracian king’s daughter Ergenia is a stereotype, the treacherous seductress of Hercules; in the film, she’s a different stereotype, the morally upright but frail and endangered damsel whose existence is centered on protecting her child. Moore’s Hercules has a young man, Meneus, as his lover; Rockules removes Meneus and fuses his youngster-itching-for-a-fight role with the character of the source-text’s narrator, Iolaus. (The effect is a probably-unintended, very slight allusion to ancient variants of the Herakles myth-cycle in which Iolaus is Herakles’ lover instead of, or in addition to, being his nephew. We might also see a reference to the homosocial “bromance” between Hercules and Iolaus in the 1990s Kevin Sorbo Hercules: The Legendary Journeys TV show.) It’s striking that Rockules doesn’t end with the hero getting the damsel, but it’s also striking that characters with non-heteronormative sexuality are flattened out and toned down.

Another major cleansing is the violence. The comic books are bloody and visceral. Indeed, Moore’s express goal was to set his Hercules in a gritty, supposedly more realistic version of the Bronze Age. It’d be an R-rated comic, but it’s a PG-13 movie, in contrast to the faithfully violent, R-rated film adaptation of Frank Miller’s 300. The violence is, like the sexuality, toned down. A turning-point in the book, a scene in which Hercules is brutally tortured, is changed substantially, for example.

But it’s not just gore that’s cleansed. In the comic books, Hercules’ ally Tydeus is a connoisseur of human brains, in an homage to certain ancient versions of his tale in which he chows down on Melanippos’ brain during the Seven’s assault on Thebes. In the movie, Tydeus is literally muted — recast as a sufferer of post-traumatic stress disorder, he speaks only as he is dying, and then only speaks Hercules’ name — and the barest hint of his cannibalistic tendencies is his licking some blood from a corpse off of his finger. Hercules himself has lost the murderous-rage tendencies he had in the comics, and along with them he has lost the moral ambiguity and psychological ambivalence that Moore granted him. The film indeed goes out of its way to absolve Hercules of the deaths of his wife and children. (Edith Hall sees this as a lost opportunity and disappointing flattening of the ancient figure.)

At the same time as moral ambiguity is replaced with typical movie heroism, mythic certainties in the comics are cleansed and replaced with doubt and euhemerism. In a commonplace for recent Anglophone movies on Graeco-Roman mythic themes, the protagonist repeatedly expresses doubts about the existence of or importance of the gods. (Unlike other iterations of this topos, Johnson’s Hercules isn’t persuaded of their existence/importance by the end of the film, and instead actually topples a colossal statue of Hera in her temple in his victorious final battle, with no sense offered of impiety or consequence, à la Achilles in the first battle of Troy. Jim O’Hara points out to me that Hercules’ expressions of doubt about the gods echoes Theseus’ own in Euripides’ Herakles.) Mythical beings like the Hydra, Cerberus, and centaurs are given rationalizing human explanations, the invulnerability of the Nemean Lion’s hide is called into question multiple times, and the Labors that Hercules is said to have completed himself, the Lion and the Erymanthian Boar, are shown in the end-credit sequence to have been the achievement of his adventuring party. By contrast, in the comics, Hercules is without doubt the son of Zeus — as his comrade Autolycus is without doubt the son of Hermes — and the Labors are presented, in their single-page cameo, as undertaken against the monstrous creatures of the myths.

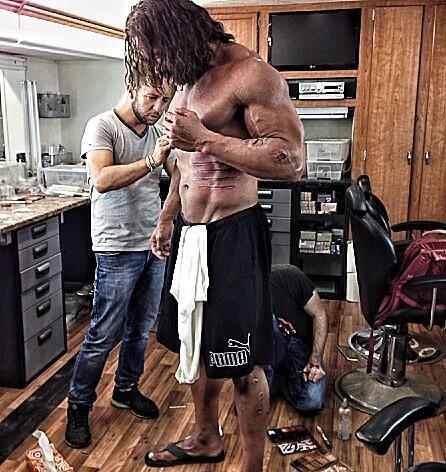

Why drain so much of the mythic material from the Hercules tale? After all, recent movies like Thor and Avengers (if not Green Lantern) show that it’s feasible to make a successful superhero movie containing gods and supernatural monsters and aliens, and 300 added in mythic elements like giant rhinoceroses and bomb-throwing wizards. In essence, I think that it runs parallel to the scars that Hercules has in Rockules: this Hercules is meant to be just an impossibly awesome version of a human, perhaps the Platonic form of The Rock himself, but still human, and in a human world. Thus the tribulations Hercules experiences are ones we might experience, the enemies he faces are ones we can find in the real world, and we as viewers don’t have to expend too much effort on symbolic interpretation to make Hercules relevant to us. (Amphiaraus’ closing voiceover about heroism suggests as much — before undercutting itself with the immortal words “But what do I know? I’m supposed to be dead right now.”) It’s of a piece with the most recent cinematic version of Superman, whose weaknesses and doubts are made manifest, and who feels and acts more like a Batman than like a Superman: moviemakers think we want our heroes to be vulnerable and damaged.

Why drain so much of the mythic material from the Hercules tale? After all, recent movies like Thor and Avengers (if not Green Lantern) show that it’s feasible to make a successful superhero movie containing gods and supernatural monsters and aliens, and 300 added in mythic elements like giant rhinoceroses and bomb-throwing wizards. In essence, I think that it runs parallel to the scars that Hercules has in Rockules: this Hercules is meant to be just an impossibly awesome version of a human, perhaps the Platonic form of The Rock himself, but still human, and in a human world. Thus the tribulations Hercules experiences are ones we might experience, the enemies he faces are ones we can find in the real world, and we as viewers don’t have to expend too much effort on symbolic interpretation to make Hercules relevant to us. (Amphiaraus’ closing voiceover about heroism suggests as much — before undercutting itself with the immortal words “But what do I know? I’m supposed to be dead right now.”) It’s of a piece with the most recent cinematic version of Superman, whose weaknesses and doubts are made manifest, and who feels and acts more like a Batman than like a Superman: moviemakers think we want our heroes to be vulnerable and damaged.

Whereas Rockules brings Hercules down to earth even more than Steve Moore did, the grit and grime of Moore’s “Bronze Age” setting and the complexity of its sexual landscape are effaced (though a review by Trie at The Rainbow Hub sees the film’s reduction of the number of sexualized women as an unambiguously positive change). I’d suggest that these two adaptation decisions go hand in hand in putting this Hercules in line with standard action-movie heroes. Although Dwayne Johnson didn’t have a producer credit in the movie, it’s conceivable that he could have used his star-power influence to have the homoeroticism taken out — but it’s more likely in my view that this modification was a directorial decision in line with the de-homoeroticization of the Spartan soldiers in the movie adaptation of 300. Defining Ergenia by her maternity and by her weakness makes Hercules the protector figure, the alexikakos, while getting rid of Hercules’ boytoy removes a possibly controversial, and certainly mainstream-audience-distracting, story element. Similarly, erasing Atalanta’s complex sexuality allows the movie to buttonhole her as a sidekick and spend less screen time on her characterization. The same goes for Tydeus: PTSD is a familiar part of the action-movie genre nowadays (witness Iron Man 3), but craniophagia is not.

For more on Steve Moore’s Hercules comics, see Gellar-Goad & Bedingham, forthcoming in Electra volume 3.