Clifford Robinson

July 24, 2023

The Ugarit iAligner is an online tool for manually aligning the words of two or three texts and indicating that a word or phrase in one text translates a word or phrase in another. Users create data that can be analyzed or visualized along with the growing corpus of data in the Ugarit collection of aligned translations. You can search Ugarit’s dynamic lexicon for a specific term within any of the 49 languages represented so far, including Latin and Ancient Greek. The platform is straightforward enough that users with no proficiency in coding can contribute their efforts to a broader project of collecting manual alignments, preliminary to applications of statistical machine translation.

Ugarit opens new possibilities for bringing participatory philology into the language classroom, and even into courses on classical culture taught in English. It can engage students in unfamiliar modes of reading, bring forth unexpected insights, and cultivate the sort of philological attention that the field of Classics values so much. Ugarit also challenges scholars of classical antiquity to become more sophisticated users of the technology that supports their work; to become more global citizen-scholars, situating our work alongside a multitude of historic and modern languages and literatures; and to contribute to a communal project devoted to the production of knowledge from texts in multiple languages, making them more accessible and interoperable.

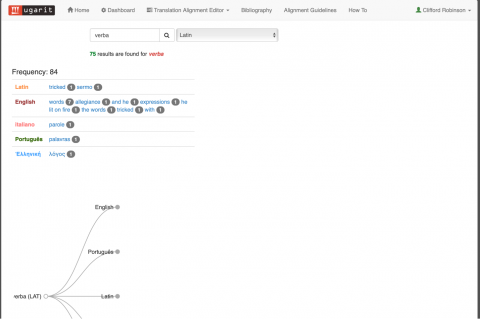

Ugarit’s potential as a multi-language lexicon can be seen in a sample search for the Latin form verba.

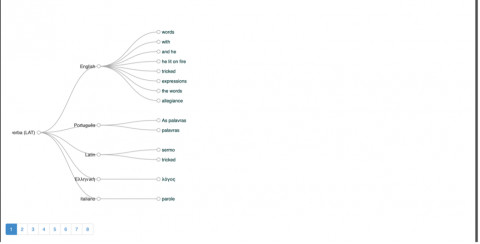

The results indicate the total number of aligned terms (75), the frequency rank of the search term in the corpus (84th), and the languages where an alignment has been established. (Enclitics as –que complicate the search, since verba and verbaque are treated as distinct items.) The tree-like representation of the results can be expanded by selecting the nodes from the branches:

The terms listed here as aligned to verba are sometimes clearly correct (“words,” parole, sermo), sometimes erroneous (“he lit on fire”), or partial (“tricked,” no doubt a gloss on the Latin idiom verba dare). Others, like “expressions,” seem to invite further analysis. It is fair to say, then, that the crowd-sourced data upon which the dynamic lexicon depends can compromise its reliability. The team of developers plans upgrades which would ameliorate this problem.

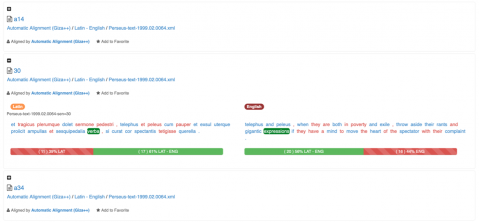

Below the tree, there appears a list of every passage where a term is aligned with the Latin term verba:

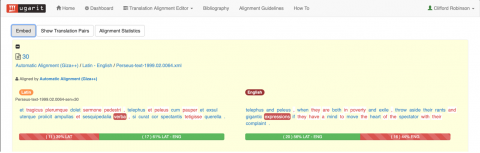

Specific results can be preserved in a favorites list included on a user’s dashboard, or they can be minimized to focus the view on a specific passage of interest. By clicking on the name for a passage (in this case, “30”), one can drill down further:

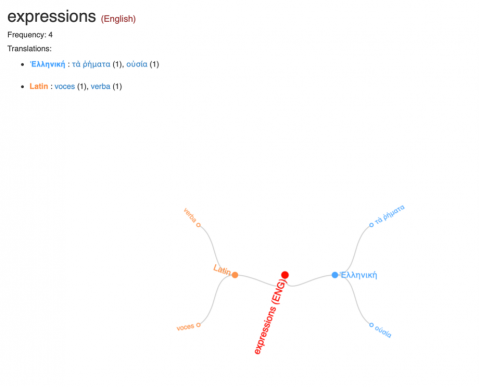

At this point, new functions become available, including a link for embedding direct citation of this alignment, a list of aligned pairs featured in the passage, statistics pertaining to the aligned texts’ correspondence, and an interactive rendering of the parallel passages in Latin and English. In the image above, I have moused over the token verba in the Latin passage, which automatically highlights that item and the aligned token in the English passage. By clicking on an item in either passage, such as the word “expressions” in the English passage, one can examine it yet more closely:

In this new view, the English term “expressions” comes into focus, and one learns that it occurs four times in the database, that it has aligned terms in ancient Greek and in Latin, and what those terms are. From here, one may follow a link to any of the items from the Translations list (e.g., voces or τὰ ῥήματα) and focus on that term for the same sort of analysis which we have just now seen for the term “expressions.” The paths through this labyrinth of language ever continue, revealing continuities and breaks along the way.

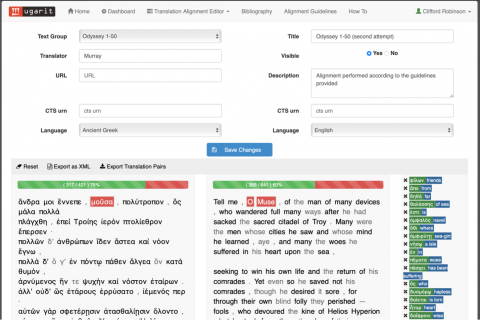

Ugarit’s Text Alignment Editor, its other main functionality that supports the dynamic lexicon, allows users to enter two parallel sentences or passages by copying and pasting or by typing. (The window can time out, so copying and pasting from plain text is recommended.) Texts can also be imported through a Canonical Text Services universal reference number (CTS urn), but these imported texts must be carefully proofread so that spaces between tokens and punctuation will be optimized for use with the Translation Alignment Editor. Having selected the correct language for each passage from the options provided, users proceed to the Editor by selecting “Align.”

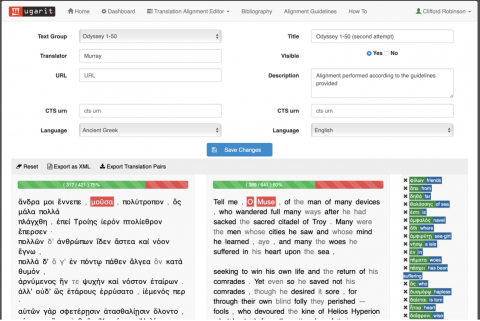

Here is a passage from Odyssey 1, together with Murray’s translation:

Boxes at the top of the page capture metadata, and there is an option to make the alignment visible within the database. You click on specific words to save them to a list of paired terms. Once an aligned pair has been established, its tokens are shown in black — as opposed to grey for unaligned tokens — and the pair is revealed as a highlight in each text. From this example, it should be evident also that more than one token in one passage can be aligned to a single token in another, so that it is possible in the Editor to align a specific word to a phrase (or vice versa).

Ugarit was first developed to acquire crowd-sourced, aligned interlinguistic tokens as training data for more complex applications of statistical machine translation, such as automatic translation alignment, a facility of Ugarit now available as a Beta release. The latest updates to the website feature a bibliography of scholarship relevant to the project, numerous tutorials and workshops on Ugarit’s potential for use and development, and newly developed guidelines aimed at establishing standards for producing “gold standard” alignments.

In my experience with students in the classroom, novice users generally take to the Translation Alignment Editor itself rather easily. One difficulty novice users may experience involves saving changes. In the center of the image above, there appears a blue box with a disk and the phrase “Save Changes” in white characters. By clicking on this box, users may save all the changes which they have made to the database which serves Ugarit as a whole. However, to produce a list of alignments from the passages featured in the Editor’s interface, users must also save each individual alignment. This simple operation involves clicking on one or more tokens in one passage and then proceeding to select one more from each other passage; finally, one clicks on a small disk icon which appears at the top of the panels in which the passages are presented as parallel texts. I have had students report losses of data due to sessions timing out, and I suspect that, often, they are not properly executing the two-step sequence of saving each aligned pair within the Editor and then finally saving all these pairs to the database through the “Save Changes” function.

While the most obvious pedagogical use of Ugarit would be in the language classroom, I have used Ugarit in a course taught in translation — in fact, as I’ll explain, I believe Ugarit can be deployed to expand our sense of what it means to teach in translation. For my Spring 2020 sections of a General Education seminar on Ancient Science, as part of what I call the “Timaeus Translation Project,” I assigned a conventional reading of a reliable translation of the text. Then my students and I devoted a session to a seminar-style discussion of the dialogue. Then, I divided responsibility among student groups for the speech of Timaeus (27d–92c). Each group employed Ugarit’s Translation Alignment Editor to align about one (Stephanus) page of the speech in three different ways. Students first aligned passages from Robin Waterfield’s excellent translation of the Timaeus with corresponding passages from Benjamin Jowett’s classic translation. Aligning two historically distant English translations of the same source text invited students to consider how much a translator’s choices may depend upon factors such as historical context, social change, or personal idiosyncrasy. Intralinguistic alignments are relatively rare and of considerable value as training data for machine learning and machine translation. Even though students almost always come to my Ancient Science course with little or no knowledge of the relevant ancient languages, I encourage students to align not only English translations of Plato’s text, but also certain tokens from the surviving portion of Cicero’s Latin translation of the Timaeus and Plato’s original ancient Greek.

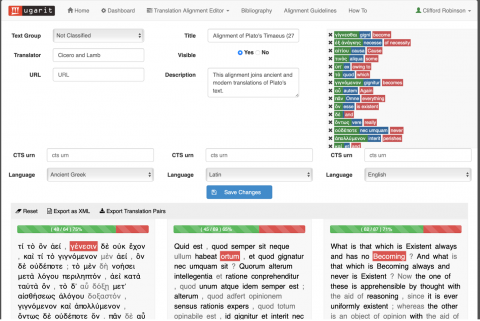

Once familiar with the Ugarit interface, they extracted their aligned pairs as a CSV file and identified ten pairs which they found most deserving of further analysis and discussion. I then assigned two further alignments: 1) Lamb’s English translation of the Timaeus with Plato’s ancient Greek text and 2) Lamb’s translation and Plato’s text together with a third, Cicero’s Latin translation. I asked the students to identify one of the Stephanus paragraphs (e.g., 59a) where the greatest number of their ten pairs occurred and to align the tokens from Lamb’s corresponding English text — which can be identified easily enough through careful reading — first with the ancient Greek text and then with both the ancient Greek and Latin texts of Plato and Cicero respectively.

Above is my own demonstration of the triple alignment, a much more complete product than I would expect from the students. Admittedly, alignment involving unknown languages can be somewhat tedious for students, since it involves hunting and pecking with the help of a dictionary, so I keep the alignment task to a modest scale — the students end up aligning only five or so tokens — and the stakes are relatively low. In this way, I am asking the students to view the Ugarit iAligner less as a resource for producing gold-standard alignments, and more as a mode of visualization capable of illustrating relationships among source texts and translations.

For the Timaeus Translation Project, I asked students to develop short reports on their selected tokens, using resources such as the Perseus Word Study Tool, so that they might find, for example, which classical authors use the tokens most frequently and how those other authors use them. One could also bring in languages in which students may have valuable knowledge due to their differences in cultural heritage and diversity of backgrounds. Using Ugarit, this digital project also challenges its users to imagine a space in which classical texts are quite literally connected — word by word, phrase by phrase — to any other language where a representative text has been documented within the dynamic lexicon.

The greatest obstacle facing this and other crowd-sourced projects is the development of a large enough community of users. I would encourage anyone who has proficiency in ancient Greek or Latin or any of the other forty-nine featured languages to select a text and a translation and to try their hand at producing a gold-standard alignment. Doing so can be an object lesson in the digital humanities for the uninitiated, but even for those more experienced with translation technologies, it can be a contribution to a growing body of knowledge, or a provocative exercise in reflection on the relationships among historic and modern languages, the translations operative across them, and the vast network of connections which we may weave between them.

TITLE: UGARIT — Translation Alignment Editor

DESCRIPTION: A translation alignment editor for manually aligning words, phrases, and sentences in two or three digital texts from any world language; a growing database of such aligned texts.

URL: http://www.ugarit.ialigner.com

NAME (creator or contributor): Tariq Yousef (creator); Chiara Palladino (contributor); Maryam Foradi (contributor)

PUBLISHER: [none]

PLACE: Alexander von Humboldt-Lehrstuhl für Digital Humanities, Institut für Informatik, Universität Leipzig

COLLECTION TITLE: [none]

DATE CREATED: 2016–present

DATE ACCESSED: August 19, 2021–July 10, 2022

AVAILABILITY: Free

RIGHTS: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License © 2016

CLASSIFICATION: databases, digitization, visualization, language learning tools, language processing, texts, Greek, Latin, outreach, pedagogy

Authors