Ellen Bauerle and kfbfletcher

August 8, 2015

It is a great time to be a fan of both the Classical world and heavy metal music: the two have never overlapped to the extent that they do right now. Consider, for example, the fact that in 2013 not one but two Italian metal bands, Heimdall and Stormlord, released concept albums based on Vergil’s Aeneid.

But this overlap is not a new phenomenon—in fact, far from it. Heavy metal music has drawn on the Classical world almost from its very beginnings, and this interest in the Classical world is part of a larger obsession with other times and places—both real and imagined— that is a defining characteristic of the genre. And since metal is a conservative genre (there are clear forefathers to whom almost all subsequent bands owe and acknowledge their allegiance), the interest in these kinds of subjects by earlier bands sanctioned continuous use of them by all subsequent bands.

To simplify radically, metal begins in 1969-70, with the debut of the two main forefathers of heavy metal, the British bands Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath. Both of these bands demonstrate interest in fantastical worlds and the occult. Led Zeppelin draws on the works of JRR Tolkien, referring to places or characters from The Lord of the Rings in songs such as “Ramble On” and “Misty Mountain Hop.” But they also have a song entitled “Achilles Last Stand” [sic]. The members of Black Sabbath have said that they took their influence from horror movies; from the very beginning their albums have been full of otherworldly topics, especially the occult, as is evident from the title of their band, which is also the name of their first album and a song on it (another song on that album is “The Wizard”).

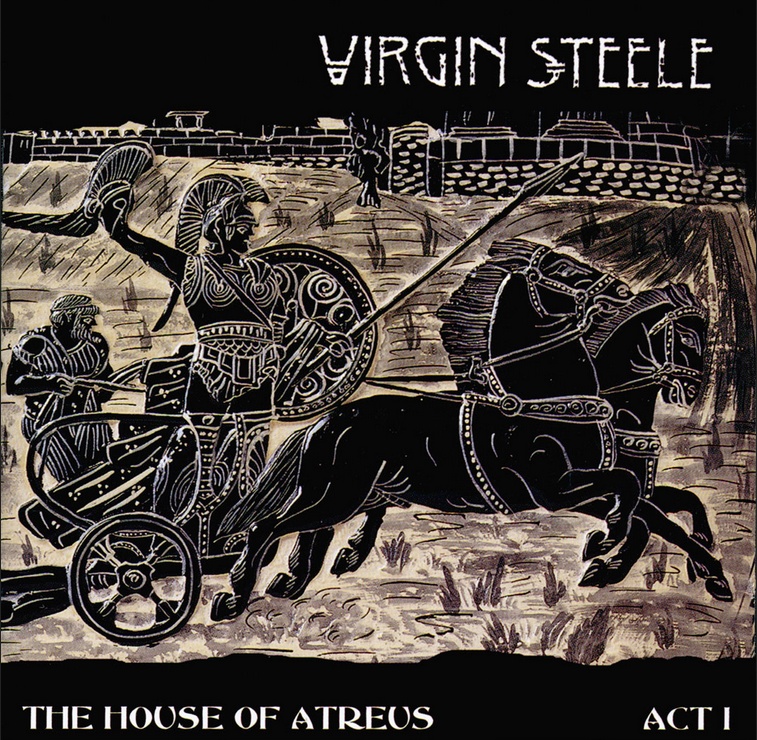

Such topics were picked up and further authorized by subsequent bands, including Iron Maiden, perhaps the most famous band of the second wave of heavy m etal, the so-called New Wave of British Heavy Metal. Their songs that draw on the ancient world include “Alexander the Great,” “Flight of Icarus” and “Powerslave” (about the Pharaohs). But they have drawn inspiration from a variety of sources, including books and movies, as with “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” based on Coleridge’s poem of the same name, and “To Tame a Land,” based on Frank Herbert’s science fiction classic, Dune. Iron Maiden’s use of these lyrical themes is especially important because they had a formative influence on the overall appearance of metal through their characteristic lettering and use of a mascot, Eddie, who appears on almost all of their artwork. This visual idiom is an important reminder that musical genre is not just defined by the sound of the music, but also includes such things as band names, lyrical content, and tshirts. And many bands have embraced visuals from the ancient world as well, from album covers (e.g., Virgin Steele’s two The House of Atreus albums, which retell Aeschylus’ Oresteia) to music videos (e.g., Ex Deo’s “The Final War (Battle of Actium)” and “Romulus”).

etal, the so-called New Wave of British Heavy Metal. Their songs that draw on the ancient world include “Alexander the Great,” “Flight of Icarus” and “Powerslave” (about the Pharaohs). But they have drawn inspiration from a variety of sources, including books and movies, as with “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” based on Coleridge’s poem of the same name, and “To Tame a Land,” based on Frank Herbert’s science fiction classic, Dune. Iron Maiden’s use of these lyrical themes is especially important because they had a formative influence on the overall appearance of metal through their characteristic lettering and use of a mascot, Eddie, who appears on almost all of their artwork. This visual idiom is an important reminder that musical genre is not just defined by the sound of the music, but also includes such things as band names, lyrical content, and tshirts. And many bands have embraced visuals from the ancient world as well, from album covers (e.g., Virgin Steele’s two The House of Atreus albums, which retell Aeschylus’ Oresteia) to music videos (e.g., Ex Deo’s “The Final War (Battle of Actium)” and “Romulus”).

Classics has been a part of heavy metal for the genre’s entire history for multiple reasons, two of the most fundamental (and perhaps original) being escapism and power. Unlike much contemporary music, metal often avoids material from contemporary, day-to-day life. In this sense, Classics is just one means of escape, with books, movies, and even video games providing other routes, and there seems to be little difference to many of these bands between writing a song based on, say, Tolkien and writing a song about the Trojan War. The German band Blind Guardian, for instance, has done just that, and they are often referred to as “Tolkien” or “hobbit metal” for their extensive use of material from Tolkien’s Middle Earth and other fantasy worlds. Their 14-minute song about the Trojan War, “And Then There Was Silence,” is just another example of finding sources on which to draw for exciting stories.

Another way to frame this interest is in terms of the epic, primarily in the modern sense of the term as grandiose and larger than life, but not entirely removed from the ancient sense. Metal, in many ways, is defined by being over the top, in terms of dress, volume, and themes. Such music requires grandiose subject matter, and content and form reinforce each other. This sense of grandeur is evident not just in the music itself (often sweeping and bombastic), but even from the length of some of these songs. For example, Iron Maiden’s “Alexander the Great” is eight minutes long, while Symphony X’s “The Odyssey” is twenty-four minutes, and Manowar’s “Achilles, Agony and Ecstasy in Eight Parts” clocks in at twenty-eight minutes long—with a five-minute drum solo called “Armor of the Gods.”

The subject matter, length, and grand sounds of these songs connote power, which scholars and critics have long seen as one of the defining characteristics and preoccupations of the genre. They have connected this emphasis on power with the fact that this kind of music was originally played primarily by men to a predominantly male, working-class audience, which might further explain the attraction to larger-than-life masculine figures such as Achilles and Alexander. This focus on power is also reflected in the music itself, which is defined in part by its aggression and the use of heavily distorted electric guitar; the very name “heavy metal” reflects the modernity of the genre, tied as it is to technology.

In fact, in a recent geomusicological approach (“Factory Music,” Journal of Social History 4 (2010): 145-58), Leigh Michael Harrison has argued that part of metal’s sound comes from its origins in the blue-collar, industrial towns of England, especially Birmingham. This town is the home of both Black Sabbath and Judas Priest, another one of the undisputed members of metal’s pantheon, and the band perhaps most responsible for metal’s early stage look. This blue-collar background may also explain metal’s escapism, since material from the ancient world—along-side material from books, movies, and video games—provides an alternative to working-class daily life. In this regard, Tolkien and Homer are equally epic, equally mythic, and equally removed from the perceived banality of modern life.

Escapism and power also partially explain heavy metal’s fascination with Latin (there are hundreds if not thousands of songs, albums, and bands with Latin names). For some bands, Latin seems to offer a certain otherworldliness, in part because it is old and connected to the arcane (we might compare the use of pseudo-Latin in the magic spells in Harry Potter). But there is often a deeper interest in Latin. Many of the bands that use Latin have a religious interest in it because of its connection with the Catholic Church. The German band Helloween, for instance, has a song entitled “Lavdate Dominvm,” composed entirely in Latin. The flipside to this Catholic interest in Latin is its connection with Satanism. To whatever extent individual bands are actually committed to it, Satanism is a hallmark of more extreme forms of metal, such as death metal and black metal, and these bands tend to use Latin more than those in other subgenres. For most bands, however, Latin seems to be a way to elevate and add weight to a band’s message, in a way perhaps not dissimilar to the reasoning that drives people to call up Classicists and ask them how to say something in Latin for a tattoo. Even if these bands are interested in the religious issues rather than Latin per se, the use of Latin, like the use of Classical myths and historical figures, gives the music a depth and weight it would not otherwise have.

In recent years, more and more metal bands have begun to use material from the ancient world, and they have done so in increasingly sophisticated and elaborate ways. As metal has developed and spread over time, its engagement with the ancient world has developed, too, and is no longer predicated solely upon escapism and power. This deeper engagement is most evident in the role of nationalism in metal’s use of Classics, as many musicians draw upon the history of the places from which they come.

This choice of subject matter is perhaps most apparent with Greek and Italian bands, who have an obvious connection to the ancient world, fostered in part by educational systems that often require students to study Greek and Latin, respectively. In Greece, for example, the band Sacred Blood has released concept albums about the Battle of Thermopylae and Alexander the Great, and another one called Argonautica. The Greek black metal band Kawir has written songs in ancient Greek, and performed in some of the pagan rituals held at ancient sacred sites. In Italy, White Skull wrote their album Public Glory, Secret Agony about Julius Caesar and Cleopatra, and Ade (the Italian name for “Hades”) released a concept album about Spartacus.

Outside of Rome, but in former parts of the Roman Empire, bands also write on topics relevant to their particular region’s history, often from an anti- Roman perspective. The German band Rebellion released a concept album called Arminius—Furor Teutonicus about the victor over the Romans in Teutoburg Forest, and the Dutch pagan metal band Heidevolk wrote a concept album, Batavi, about that German tribe’s changing relationship with Rome. The Swiss band Eluveitie’s album Helvetios provides a view of Caesar’s Gallic wars from a Celtic point of view. These bands have an obvious connection with their subject matter through geography, and their perspective on the past tends to be shaped by nationalistic ideas. But even these bands do not limit themselves to Classical material, as they use other fantastic and historical material. White Skull, for instance, also put out an album about the Vikings, while Rebellion released a concept album based on Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

Outside of Rome, but in former parts of the Roman Empire, bands also write on topics relevant to their particular region’s history, often from an anti- Roman perspective. The German band Rebellion released a concept album called Arminius—Furor Teutonicus about the victor over the Romans in Teutoburg Forest, and the Dutch pagan metal band Heidevolk wrote a concept album, Batavi, about that German tribe’s changing relationship with Rome. The Swiss band Eluveitie’s album Helvetios provides a view of Caesar’s Gallic wars from a Celtic point of view. These bands have an obvious connection with their subject matter through geography, and their perspective on the past tends to be shaped by nationalistic ideas. But even these bands do not limit themselves to Classical material, as they use other fantastic and historical material. White Skull, for instance, also put out an album about the Vikings, while Rebellion released a concept album based on Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

For someone interested in the Classical world, then, heavy metal provides an astonishing array of songs, videos, and albums to enjoy. But if it is a great time to enjoy music about such topics, it is also a great time to study such music. In Classics, the increased attention to reception means that we are becoming increasingly aware of how fluid our conception of the ancient world is, and how much it depends on the countless reimaginings and adaptations between then and now. Metal offers another set of voices to this discussion, and is especially valuable because of the sheer quantity of material and its truly international range.

And metal itself is finally beginning to receive its scholarly due. Metal studies is a burgeoning field, which can now even boast its first journal, Metal Music Studies, the journal of the International Society of Metal Music Studies. It should come as no surprise that the very first issue contains an article entitled “The Metal King: Alexander the Great in Heavy Metal Music” (C. T. Djurslev, MMS 1 (2015): 127-41). Scholars from disciplines such as cultural studies, sociology, and musicology have turned their attention to metal and focused on topics such as nationalism and the formation of identity through music, thus complementing some of the main topics of Classical reception studies.

And there is something else we can take away from all of this: the existence of these numerous songs and albums is a testament to the continuing appeal of this history and literature, and a reminder that this appeal is not passive; people from all walks of life and from all over the world are motivated to interrogate and respond to these texts, and to create their own texts. In this way, these songwriters share the same inclinations as artists have had since the ancient world. Finally, these songs should remind us that we as Classicists do not control this material, and that students come to it in ways we may not even be able to imagine, often long before they find themselves in our classes. As heavy metal is in part defined by its use of Classical material, so Classics in the modern world is in part defined for many by its appearance in heavy metal.

A Beginner’s Guide to Classics in Heavy Metal

Iron Maiden (UK), “Alexander the Great,” Somewhere in Time (1986): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1oTEQf1d9Iw

Manowar (USA), “Achilles, Agony and Ecstasy in Eight Parts,” The Triumph of Steel (1992): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0AnLvPs6JE

Helloween (Germany), “Lavdate Dominvm,” Better Than Raw (1998): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KwR47IAIOdA

Symphony X (USA), “The Odyssey,” The Odyssey (2002): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BhOCvwtrdsA

Ex Deo (Canada), “The Final War (Battle of Actium),” Romulus (2009): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcfaltp8CL0

Eluveitie (Switzerland), “A Rose for Epona,” Helvetios (2012): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_1lXdLus2WI

Sacred Blood (Greece), “Ride Through the Achaemenid Empire,” Alexandros (2012): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Y1g1-kt-sU

Kawir (Greece), “Εις Δήμητρα,” Ισόθεος (2012): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AF3xQ-383ww

Ade (Italy), “Sanguine Pluit in Arena,” Spartacus (2013): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nV8ktJRTxJg