Nandini Pandey

July 10, 2020

In light of the present administration’s brazen disregard for facts and the public good, you’ve got to admire past leaders’ nonpartisan concern to preserve knowledge for the future.

Two recent episodes of the “Radiolab” podcast made me nostalgic for federal preparation for various Cold War Doomsday scenarios -- down to the reassignment of the National Parks Service to run refugee camps and the Post Office to register the dead. One episode detailed the artifacts earmarked for preservation in case of nuclear armageddon, from obvious picks like the Declaration of Independence to odder ones like the log of the USS Monitor and Lincoln’s autopsy report. The other episode explored ideals of preservation on another level, through the challenge that physicist Richard Feynman posed to his undergraduates in 1961:

If, in some cataclysm, all of scientific knowledge were to be destroyed, and only one sentence was passed on to the next generation of creatures, what statement would contain the most information in the fewest words?

In a real apocalypse, of course, I’d be too busy panicking to contemplate this thought-experiment. But amidst the present anxiety and uncertainty, I started wondering what a “cataclysm sentence” might look like for classics. What would we choose to pass on to posterity from a field that’s already built on scraps of the past? And what would the texts and objects we chose to preserve say about us and our mindset during this pandemic? I asked a few scholars to share the “cataclysm sentence” (or artifact) that best encapsulates all they’ve learned from classical antiquity, what they hope to give students, and what they’d choose to leave to posterity.

Joel Christensen, Associate Professor and Chair of Classical Studies, Brandeis University

At best, what do we have, a minor proportion of what we think was composed in the Ancient Mediterranean? And over 5 percent of that is Galen! Classicists love to play the game of what text would you trade that we have for something we’ve lost. (Well, those who don’t just try to counterfeit it…) The real horror of this is our arrogance: we play this game without understanding the extent of our own ignorance.

But, what if we reverse it, if instead of dealing from a seeming abundance, we must trade our riches in and flee, like Aeneas with Anchises on his back, with just a few precious words? Are we going to demand both beauty and truth from a single line? Do we want to be inspired? Do we want something useful? (Ah, Homer, maybe it would have been better never to have lived than to see these days!)

I know what I would save because I have been carrying it around in my head for years, troubling over it like a mantra or a koan. Early in the Odyssey (1.32-34), Zeus looks down on Aegisthus as he screws up his life and complains,

Mortals, they’re always blaming the gods

claiming that evils come from us and then they themselves

have pain beyond their fate because of their own recklessness.

These lines are programmatic to the Odyssey—readings that don’t convey the fact that the narrator makes the same statement about Odysseus’ companions at line 7 earlier or later the companions and ultimately Odysseus himself miss out on the fact that the Odyssey invites its audiences to think about agency, causality, and responsibility.

See, the world of the Odyssey is not the world of the Iliad—where all of the Iliad is, allegedly, part of Zeus’ “plan.” The Odyssey presents a more complex view of human decisions, divine complicity, and the way we all navigate the world together. These lines force us to think about determinism and “free will”. However we define our freedom to act—and I like to use “sense of agency” to make it clear that the appearance of our ability to choose impacts how we act in the world—we are constrained by things we can’t control: society, biology, environment, butterflies in unknown lands. And then there's whatever apocalypse of the week is assailing us. (So, “the gods”). I think this lesson, simplified, repeated, and taken to heart is invaluable, whether we’re fleeing wrecked cities or trying to log in to a zoom meeting a few minutes late. See also: Climate change; Police brutality; COVID-19 response, faculty writing syllabi the day classes begin....

I know. I know. This was supposed to be one line. So I will take this: “they suffer pains beyond their fate because of their own recklessness”. This is more than Sarah Connor’s “no fate but what we make” because it acknowledges that we can’t control things but teaches the lesson that we make many things worse.

I am really going for truth and hope here: see, I’d like to think that Zeus’ line implies a corollary as well: if we aren’t reckless—or stupid or evil, whichever atasthalia you prefer—we might just be able to make our lives better than they were supposed to be.

Dan-el Padila Peralta, Associate Professor of Classics, Princeton University

But why did George Floyd have to die? Ahmaud Arbery? Breonna Taylor?

Hannah Čulík-Baird, Assistant Professor of Classical Studies, Boston University

In the 2nd century CE, the Greek scholar, Zenobius, wrote that the phrase “sillier than Praxilla’s Adonis” was apparently used to describe stupid people. To explain this proverb, Zenobius quotes part of her Hymn to Adonis:

In her hymn this Praxilla represents Adonis, asked by those in the underworld what was the most beautiful thing he left behind when he came, answering like this:

The most beautiful thing I leave behind is the light of the sun;

second, the shining stars and the face of the moon;

also ripe cucumbers [sikyos] and apples and pears.

Anyone who counts cucumbers and the rest as equal to the sun and moon can only be regarded as a foolish person.

We’re lucky to have this bit of Zenobius. Not only because he preserves a sweet segment of Praxilla’s clever hymn (she plants a reference to her hometown, Sicyon, among the fruits; she imagines Adonis longing for the cucumber, used by women in their worship of him), but because he demonstrates how wrong-headed and misogynistic scholars can be.

Figure 1: Fragment of an Attic red-figure vase (c. 430 BCE) with women celebrating the Adonia. They sowed seed at midsummer on rooftoops so that the fruit would soon wither.

Amy Richlin, Distinguished Professor of Classics, UCLA

exegi monumentum aere perennius

I have built a monument more lasting than bronze.

Things change. When my colleague Michael Haslam abruptly found he needed to retire by the end of the term, he piled up all the papers from his office in a big heap in the hallway to be picked up for recycling, and taped that line from Horace in a sign on the wall above the heap. It made me think twice about what I’d thought we do. Horace is a fine poet for ending and starting over, and for the power of poetry to remember what is otherwise lost: vixere fortes ante Agamemnona. But a single sentence will never be enough for future readers to reconstruct a lost language from – so the Etruscans and the Carthaginians have found.

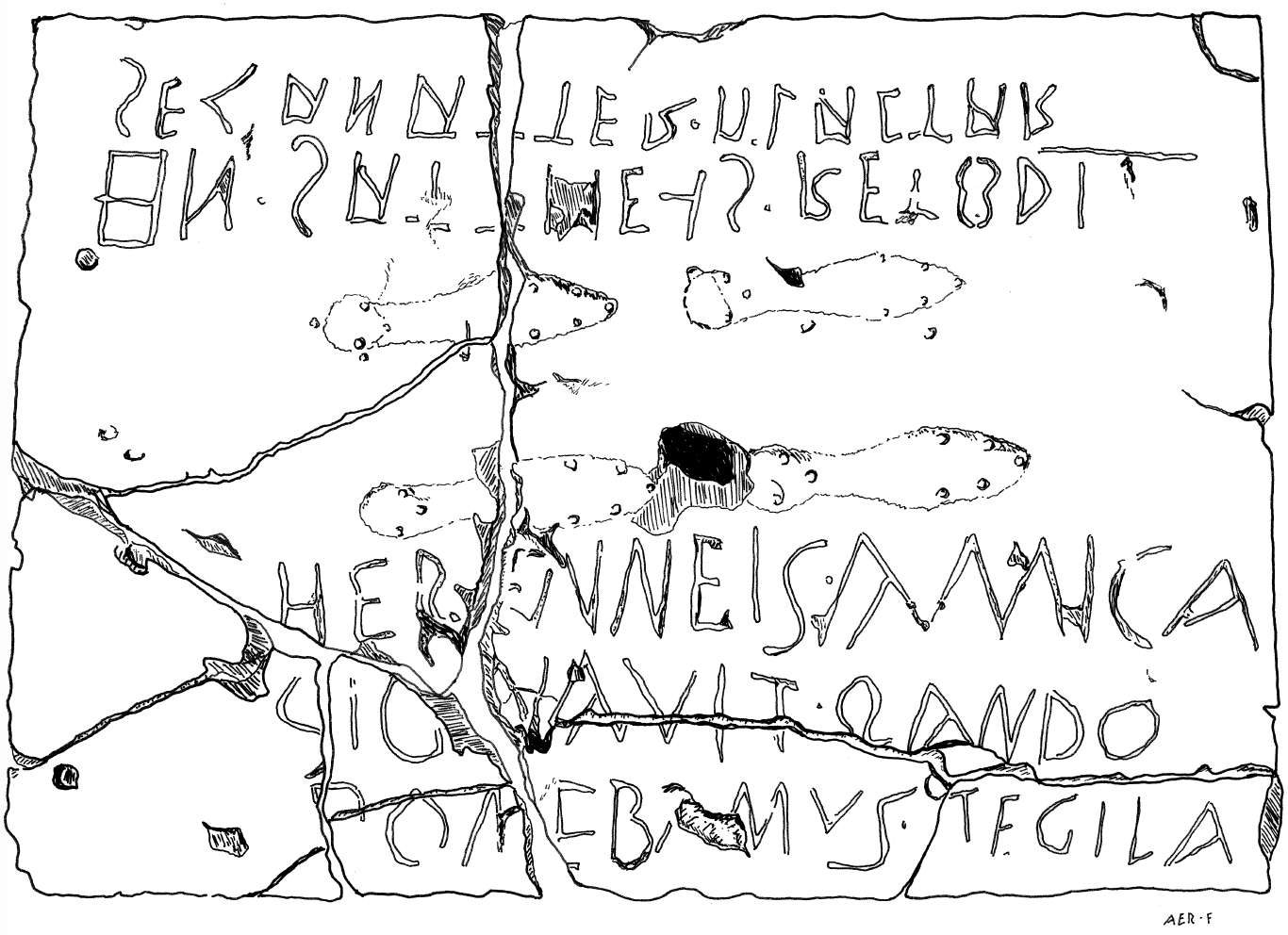

What object I would save? The Pietrabbondante roof tile: a record of a friendship between two women, both slaves, who worked in a brickyard, one who spoke Latin and one who spoke Oscan, and who left their footprints, their names, and the record of their act while they were on the job.

Figure 2: Roof tile from Pietrabbondante, Italy. Drawing Amy Richlin, after La Regina 1976.

Samuel Ortencio Flores, Assistant Professor of Classics, College of Charleston

If I could save just one object from antiquity from a destructive cataclysm, I would preserve a child’s toy, like a 10th-century BCE geometric horse found in the Kerameikos Museum in Athens. While there are thousands of artifacts from antiquity that may be imbued with deeper cultural meaning or historical value—from Minoan frescoes to the remains of religious temples to statues of gods and Roman emperors—I’ve always found children’s toys particularly fascinating. They are artifacts that could have belonged to anyone, whether a future monarch or a child born into enslavement. Either could have found enjoyment in this object. It is therefore worth preserving, because it is a lasting sign of our shared humanity and it gives voice to the millions of people from antiquity whose stories we will never hear. It is a testament to those who were not able to build bronze statues of themselves or record their achievements in stone.

Figure 3: Little horse on wheels (Ancient greek child's Toy). From tomb dating 950-900 BC. Kerameikos Archaeological Museum in Athens (CC-BY-2.0).

Jinyu Liu, Professor of Classical Studies, DePauw University

For many years now, the following quotation has given me comfort and strength and if only one sentence were to be passed on to the next generation of creatures, I hope this would be that sentence:

omnia mutantur, nihil interit (Ovid, Metamorphoses 15.165, Pythagoras speaking), which can be translated as "Everything changes; nothing is lost."

This maxim is not a cure-all, since a lot of things are not specified in it. In fact, it leads to a ton of questions. How long does it take for a change to take place, for example? And through whose agency does change occur? What is the manner of change? Peaceful or violent? What is the direction of change? For the worse or for the better? For this last question, I often supplement a Taoist saying:

祸兮福之所倚,福兮祸之所伏 "

Good fortune follows upon disaster, and calamity lurks with good fortune" (Laozi, Daodejing 58).

Despite the gaps, the creed that nothing stays the same all the time gives me hope, helps me cope with downturn and loss, provides me with patience, and warns me against complacency. I am often amazed to be a participant in this everlasting movement of transformation.

Yurie Hong, Associate Professor and Chair in Classical Studies, Gustavus Adolphus College

My ancient quote when facing a cataclysm would be not so much an ancient quote itself but Robert F. Kennedy’s misquotation of Edith Hamilton’s mistranslation of Aeschylus when he recited it by heart during an impromptu speech to a largely Black crowd in Chicago 1968 while announcing the news that Martin Luther King, Jr., had been assassinated in Memphis:

Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget

falls drop by drop upon the heart,

until, in our own despair,

against our will,

comes wisdom

through the awful grace of God.

I think often of these lines, inaccurate as they are, for three reasons:

- It’s a beautiful example of ancient material held so close to heart that it becomes a genuine touchstone in times of hardship. Robert Kennedy turned to Greek tragedy after his brother John F. Kennedy’s assassination. He turned to it again to process the crisis of anti-Black violence and injustice manifested at that particular moment by the assassination of MLK. When he needed to connect the dots of violence and injustice, pain and the harshness of the world, and some kind of hope or purpose, Aeschylus (or Edith Hamilton’s version anyway) was there to help him. When the world seems to be falling apart around you, stepping back and taking a look at the vast scope of human existence can be a balm. (That’s not actually the sense of the original, which comes early in Aeschylus’ play and places more emphasis on divine inexorability and our inability to avoid pain and confusion and only understand it after the fact. Given that we’re still wrestling with white supremacy and the brutalization of Black lives, though, the historical context ironically parallels the literary one.)

- I also love the image. It captures beautifully the dull ache of a deep, chronic grief experienced over time and that feeling of how powerless we are to change the past. But it also seems to hold forth the promise that all that suffering will not be in vain. One day you will be able to make some sense of what has happened and arrive at the peace that comes with meaning and acceptance -- essentially, wisdom -- and that will be your reward.

- This purported connection between wisdom and suffering gives me a lot to wrestle with. Because, as comforting as it is and as much as I value the struggle to make sense of the hard things in life, it’s not always true. Suffering does not always lead to wisdom. Or, even if it does, that suffering may be far too high and unjust a price to pay. In these times — as we see over 100,000 people die needlessly while Trump and his administration willfully mismanage the Covid-19 pandemic; as we see Black and Indigenous men and women being brutalized over generations by our various institutions — I think I’d prefer a bit less wisdom and a lot less suffering. Unlike in Aeschylus, though, where there really is nothing you can do against the gods, these are human institutions and human problems. We humans have the power to fix them. Wisdom is not enough. Action is better.

Diana Spencer, Professor of Classics, University of Birmingham

A sentence: ‘Why study classics?’

The literary expression of self-entwined-with-environment that courses through classical texts shows that every action seeds the possibility for perspectival change, and offers the opportunity radically to transform the universe, the group, and the individual, through myth making, and in the interrogation of where power (words, syntax, systems; fear, love, creation, destruction) is located — or locates itself.

To me, one of the most powerful ways that ‘classics’ speaks is in its tangled identities — it is the tangled skein rather than the ‘woven’ text. I experience classics as something like a knot whose significance is vested in the ways that knots are at once one and multiple, string and loop, bi-directional and multivalent, and meaningless without something around and amidst which to be entwined — joining, stabilising, holding apart, giving structure, challenging whilst also delighting in linearity.

The ‘past’ is not ‘us’, any more than ‘we’ are exceptionally or verifiably ‘now’; but ‘the past’ roots humans as living organisms in a collectivising metonymic field. ‘The past’ is a myth told by humans, but also produced by other actors, not necessarily sentient, in ways we cannot understand but should reflect upon. In the study of classical materials I find strange, porous media that allow me to leach into alternate universes, and in turn to be aware of the potential of the alterity of Others to seep into mine.

These senses of fracture and leakage as a promise of possibility are underpinned by Lucretius’ gaudy (e.g. 2.748-841, on colour and mutability and the dynamism of ‘stuff’), sombre, and inquisitive poem on the nature of the Universe (De rerum natura). Epic verse on a topic by turns micro- and macroscopically treated, Lucretius lines up cosmic forces and human urges and compels them into glorious conversations that make real the notion of an omniverse in which everything is possible and the probable dances to refreshingly inhuman tunes (e.g. 2.963-1022, on the shared ‘seeds’ which produce all matter, and all life).

Pay attention now, and all times are now, and everything changes every time we pay it attention’ (DRN 2.1023-1029).

This is what I take from Lucretius, and classics as a field.

Alice Mandell, Assistant Professor of Ancient Near Eastern Studies, Johns Hopkins University

My "cataclysm sentence" is really one version of the exchange between Gilgamesh and the tavern-owner Siduri. I love Siduri's reply to Gilgamesh (here in Andrew George’s translation of the Standard Babylonian version, from Sippar). He is looking for immortality and she asks him to consider the here and now: the pleasures of the body, family, and love.

If I was telling this story today and acting in the role of Siduri I would say: be present and cherish love, however it comes to you, and those interpersonal ties forged by kinship, community, and life experience.

Said the tavern-keeper to him, to Gilgamesh:

' Gilgamesh, where are you wandering?

The life that you seek you never will find:

when the gods created mankind,

death they dispensed to mankind,

life they kept for themselves.

But you, Gilgamesh, let your belly be full,

enjoy yourself always by day and by night!

Make merry each day,

dance and play day and night!

Let your clothes be clean,

let your head be washed, may you bathe in water!

Gaze on the child who holds your hand,

let your wife enjoy your repeated embrace!'

There are as many directions to take this question as there are classicists, of course, and the few I asked are just a tiny sampling of our diverse field. But in these times when so much seems under threat -- our health, our jobs, our plans and paychecks this fall -- it’s some consolation to remember that the things and ideas we study have survived worse than this. It is also therapeutic to think through what we assign lasting value and why.

Authors