Aimee Hinds

January 24, 2019

I love Classics, but it isn’t my first love; that was art, specifically Pre-Raphaelite art. A visit to my local museum with school introduced me to them, and my eight-year-old self thought it was fate when I found a painting with my name that I thought was by Edward Burne-Jones (Amy by Arthur Hughes; it wasn’t spelt right but it wasn’t often anyway, and still isn’t). A postcard sent shortly after the museum visit by a relative, featuring A Mermaid by John William Waterhouse (but wrongly attributed on said postcard to Burne-Jones) cemented my love of the Pre-Raphaelites, and Burne-Jones in particular.

Fast forward four years. I’m introduced to my second love – and the reason I’m writing this – Classics. Classics wasn’t my goal: I chose Latin over German as a foreign language at secondary school, with a view to becoming a veterinarian. Being a vet didn’t sound as glamorous as being an artist, so I eventually plumped for art. But Classics stayed very close to me, trumped as a subject for study at university only by my great ambition to get paid to paint pictures like Edward Burne-Jones.

At art school I quickly fell out of love with art, or at least, with the world of art. I was out of my depth: brown-skinned, working-class, a first-generation student who had to rush off to work after lectures to be able to afford to attend. I dropped out after two semesters. I tried again the next year, and applied for a place on a History of Art course, was accepted, and this time lasted only one semester. After two attempts I still didn’t understand then why I didn’t feel like I belonged there, and so applied a third time.

Image via Wikimedia under CC0 1.0..

By this point I had begun to disengage with the art world, feeling that as a woman, and as a woman of color, the art that I most liked to look at didn’t want me as a viewer. Pre-Raphaelite art is full of ethereal white women painted by scholarly looking (although bohemian for their time) white men who in many cases were abusing those same women. Convinced art was the problem, I turned to my second passion and applied to a Latin course in a different city. I was accepted again but deferred entry, still unable to put my finger on quite what I found so daunting. When the letter came the next year asking me if I would be attending, I declined. I went to work full-time and put my university experiment to bed.

Fourth time lucky, I went back to university, distance learning to study Classical Archaeology and Ancient History, where I could blend both loves. I enjoyed the distance-learning experience immensely, and only later did I reflect that my anonymity certainly played a role in that. In one sense, I am rather lucky that my name gives nothing away about my ethnicity – and so I could rely on being judged solely on my work. I enjoyed it so much that I went straight on to a Master’s course in the Classical Mediterranean, campus-based. A bit more self-aware and having digitally met most of my professors, I wasn’t scared off by the lack of diversity in my classes and around my School’s building, but I did finally understand that this was one of the reasons that I had never felt welcome during my previous university stints. This time I made my face fit. I was well supported by staff and made to feel like I belonged by other students, but I was always well aware that I had no professors of color to turn to, and few non-white academic peers.

But any student of color will tell you that these things aren’t perfect. I was asked by one white graduate student if I didn’t think that black students didn’t want to study Classics because their parents were adamant that they would earn more money studying business or law. Another student of color told me of instances where a particular professor had continually referred to him as being from somewhere he was not, despite his correcting her. I made sure to mix almost exclusively with people who fostered the kind of environment I wanted to be in. But this came, and still comes at the price of being slightly removed from the discussion, unwilling to wade into the heart of debate for the fear of being shut out completely because of other people’s perceptions that I am not white enough to be an authority in Classics.

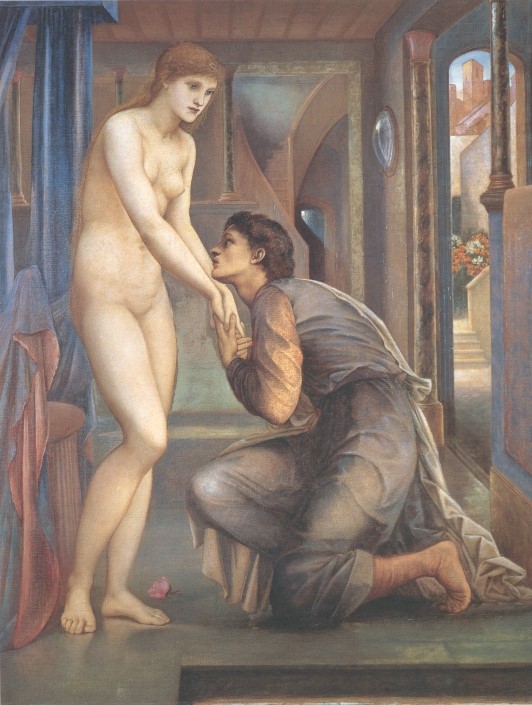

Back to Burne-Jones. If you are familiar with Pre-Raphaelite art, you’ll know that they took subject matter from, amongst other topics, Greco-Roman mythology. Many of these paintings strongly flavor modern imaginings of Medieval folklore and Classical mythology. Some notable highlights are Evelyn De Morgan’s Helen of Troy (1898), Rossetti’s Helen of Troy (1863), Pandora (1878) and Proserpine (1874), Frederick Sandys’ Medea (1868), and John Collier’s Clytemnestra (1882). Burne-Jones himself painted many mythic images from the Greco-Roman corpus, including Phyllis and Demophoon (1870; an early introduction to Greek mythology for me), several series of paintings featuring Psyche, the unfinished Perseus Cycle (1875-90s), The Three Graces (1885), and two series of paintings on the subject of Pygmalion (1868-1878).

Image via Wikimedia under CC0 1.0.

The story of Pygmalion, as told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses – Pygmalion creates a lifelike statue of a woman, falls in love with it, and Venus brings it to life – is incredibly problematic. This hasn’t gone unnoticed by artists and thinkers – in fact, it was suppressed during the Middle Ages as encouraging idolatry. After that, the tale often focused on Pygmalion’s misogyny. Pygmalion creates his woman statue because he is disgusted by female faults, prompted in Ovid’s narrative by the prostitution of the Propoetides. These issues are recognized in later works of reception too: George Bernard Shaw’s reworked version, the play Pygmalion (1912), Madeline Miller’s novella Galatea (2013), and, to a slightly lesser extent, the musical My Fair Lady (1956). Pygmalion’s misogyny is fairly obvious, and feminist re-readings are useful. But I’ve been working recently on post-colonial readings of myths. I’d been thinking a lot about the statue, most of all imagining Pygmalion’s face if his snow-white statue turned into a sun-burnished woman.

At this point I ran across this article in The New Yorker. The article notes not only that polychromy was a feature of ancient sculpture, but also its insidious exploitation by the far right and white supremacist groups to argue that they are the heirs to Classical culture. The article cites two excellent essays by Dr. Sarah Bond, in Hyperallergic and Forbes, which discuss the fact that the denial of polychromy in the ancient world props up racist and white supremacy ideologies today. I’ve seen several comebacks on Twitter to this article claiming that polychromy in sculpture is not exactly news; that’s true. But as Dr. Bond pointed out to one eye-roller, this isn’t about whether or not sculpture was colored. We know that it was. It’s about the removal of that color, and the way that it is still used, and the fact that to most people, Greco-Roman art is still blank-eyed, ivory white statues.

The polychromy articles made me think twice. In Ovid’s Pygmalion narrative, there is no indication that his statue is not polychromatic. Pygmalion’s statue is snowy-white, but that’s to be expected, because it’s the color of the marble the Romans were so fond of using. There is no mention of the statue’s color once she becomes a real woman – because in Ovid’s Rome, sculpture was a riot of color. Pygmalion’s statue probably had painted lips, and hair, and skin. When Pygmalion asks Venus for a wife like his ivory girl, he isn’t asking for a living embodiment of his white sculpture like some sort of dead-eyed ivory zombie. He is asking for a woman who is as he has made her. Given his issues with women, his desire for his statue most likely has less to do with beauty and more to do with her perceived character, which, as we find out, is modest and timid. The statue’s whiteness is an indicator of Pygmalion’s skill as a sculptor and the quality of his material, and, while the enthusiastic fondling he gives his new creation is weird (always sounds a bit more Frankenstein than Pinocchio to me), the statue’s color is never an issue in Ovid.

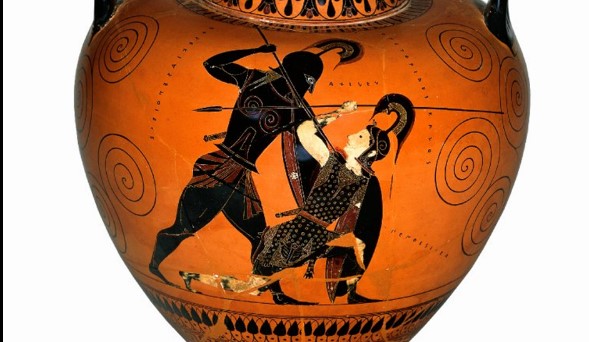

Image via The British Museum under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

So far, so good. But there’s more to this, which makes the issue of polychromy and the erasure of ethnic diversity in the ancient world even more significant. When we think of the statue, we usually think of her name as being Galatea – ‘she who is milk-white’. This in itself, again, isn’t problematic. The statue was quite possibly pale-skinned, and pale skin was an indicator of feminine beauty in both Greek and Roman worlds for the same reason it is in many cultures, because it indicates that one does not do manual work outdoors. Skin color is used in Greco-Roman art to differentiate men and women. For example, the famous sixth century B.C amphora by Exekias shows a black-skinned Achilles next to a pale-skinned Penthesileia. Even where gender is less clear-cut skin tones are used to make sense of the image. The wall painting above from Pompeii depicting Achilles on Skyros distinguishes the disguised, feminized Achilles from both the shocked Deidamia and his discoverers, Odysseus and Diomedes, and another Pompeiian wall painting depicting Hermaphroditus shows them with darker skin than their female attendant.

from the House of the Dioscuri, Pompeii. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. 9110.

Image via Wikimedia under CC0 1.0.

Literary evidence, contrary to white-supremacists of the alt-right believe, also does not support the idea that the Greeks and Romans reveled in their own white supremacy. For sure, they reveled in their difference to others, and made a big deal about how they were Better than the Others. But these differences are not based upon racist assertions. Pliny’s description of the Africans of the interior ignores skin color entirely and instead references cultural and behavioural differences.

A favorite of the alt-right, the idea that dark skin is indicative of cowardice, is taken out of context by modern white-supremacists. Aristotle says that those in cold, northern countries are courageous but unintelligent, whilst those in warmer climates, such as Asians, are intelligent but not brave. The Greeks, being exactly in the middle are of course brave and clever, being most perfectly positioned for the best of both worlds. Five hundred years later Vitruvius takes this and runs with it, explaining that the sun dries out those in hot countries, giving them dark skin and limited amounts of blood, whilst those in cold countries are fair, moist and full of blood. The lack of blood in darker skinned people makes them fearful of battle but hardy against heat and illness while all that excess blood means northerners are happy to lose a bit in a fight but are weak in the face of fever. Like Aristotle, Vitruvius places his own people – the Romans this time – right in the middle, so obviously they are practically perfect in every way. Pliny makes similar observations and claims.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. 27.200

Image via Wikimedia under CC0 1.0.

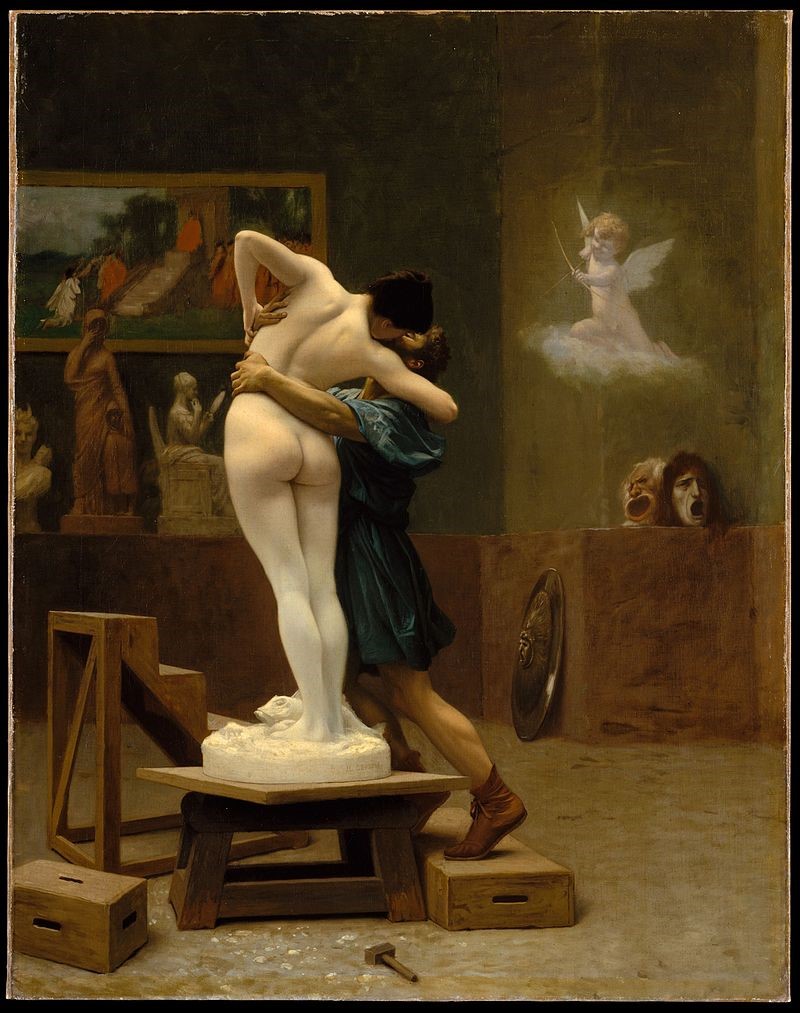

So what’s wrong with Pygmalion’s Galatea? The problem lies in the fact that Galatea is not the name of the statue as given to us by Ovid, or in fact by any ancient writer: but it has still influenced not only Enlightenment artistic and literary versions of the tale, but continues to do so today. Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Galatea, pictured above, emerges from her ivory slumber only slightly pinker than before; a Google search will turn up lots of images, from the Enlightenment to the present day, of women transforming from stiff white marble into supple pink porcelain. Burne-Jones’ Pre-Raphaelite versions are hymns to the perfection of whiteness. Burne-Jones painted two versions of the same four images, the first four in rich, dark tones we would expect of Victorian art, the second four in pale pastels. Although he never names the statue, instead calling the cycle Pygmalion and the image, it is very obviously inspired by the same intellectual and cultural reading of the myth that ended up endowing the statue with the name Galatea in the first place. The first cycle enhances the statue’s whiteness, and the second celebrates the muted tones of all involved. The first image, The Heart Desires, is so entrenched in the white glory of Greece that it also features versions of the Neoclassical statue The Three Graces – a marvel in white marble.

Image via Wikimedia under CC0 1.0.

In 1931, Helen Law noted that Galatea is not an ancient name for the statue, and a later article by Meyer Reinhold places the responsibility for the popularity of the attribution of Gatalea’s name to Pygmalion’s statue with Jean-Jacques Rousseau's musical melodrama Pygmalion in 1762 (its first use apparently being in a novel by Themiseul de Saint-Hyacinthe de Cordonnier around twenty years previous to this). This was only two years before the publication of Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s influential Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums, which perpetuated the notion of the white beauty of ancient sculpture. Winckelmann’s two volume account of art history was also hugely significant in the rise of Neoclassicism, itself a movement which often ended up adjusting rather than appreciating the beauty of the ancient world.

The production of these two very different works coincides rather neatly with the rise of pseudo-scientific racist theories in Europe. Whilst the transatlantic slave trade was in full swing (and would be abolished in North America within fifty years of this), the science of racism was only just beginning. The introduction of the name Galatea – the ossification of the statue as a pinnacle of whiteness – into Pygmalion’s myth and the contemporary publication of works of scientific racism such as Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae (1735) and Blumbach’s On the Natural Variety of Humankind (1775) are not coincidental. Like the systematic suppression of the polychromy of ancient sculpture, the naming of the statue is not an actively racist gesture but its consequences are sinister.

The other problem is that Galatea is not just an invented name for Pygmalion’s statue. She has been appropriated from elsewhere, namely from Theocritus’ Idyll XI, in which the Cyclops Polyphemus laments that Galatea, a sea nymph, does not love him. Polyphemus praises Galatea’s milky white skin, again not problematic in a racist sense as it sets her up as an erotic object of desire, but also because it parallels the Cyclops’ references to the milk of his sheep and sets the pastoral scene. The real Galatea was a favourite subject of the Symbolists, who, unlike the post-Renaissance and Victorian artists portraying Pygmalion’s Galatea, did not endow her with milky whiteness. In this case, the reception has ignored the very real whiteness of Galatea, although it does follow the lead of ancient examples which portray the Cyclops with tanned skin, differentiating him from the pale Galatea.

As we know it today, the story of Pygmalion and Galatea denies me access to both the Classics and the Arts, reinforcing as it does the notion of whiteness as absolute perfection. Like the false belief in the whiteness of classical sculpture, this was created not by ancient culture but has been perpetuated and enabled by modern Western culture. I’m not saying here that I expect to be able to read into the Pygmalion myth that the statue was given life and became inexplicably African in appearance. Ovid places the story in Cyprus, and there’s no intimation that she didn’t awake looking like any other native Cypriot woman. As Eidolon editor Yung In Chae points out in the brilliant White People Explain Classics to Us, the search for diversity in Classics is not about finding ourselves as though in a mirror. The point is that the reappraisal of this story – in other words, thinking in color – allows me to strip back hundreds of years of racist appropriation of Classical myth.

A critical reading of the Pygmalion myth in light of the issues around polychromy, issues which have sprung up due to Western culture and not the Greco-Roman cultures from which this myth springs, enables me to feel like I belong in the community. It may feel wrong in the face of feminist scholarship, but the de-naming of the statue removes the assumption of whiteness and its related racial undertones. These racial undertones are implicit in both the implied whiteness of the statue endowed by the borrowed name Galatea and in the insistence that Greco-Roman sculpture was white. Removing the statue’s name lets us go back and read Ovid’s version of the Pygmalion myth through an intersectional feminist lens, not as a love story but as a tale of control and denied bodily autonomy. The removal of the name allows for better interpretation of the real Galatea's milky whiteness, removing any trace of the taint of negative racial significance and conceding that it is, in context, about her femininity and her difference to the alien Cyclops.

Stripping post-Classical reception off myths is not easy. Just because I am not white, it doesn’t mean I automatically envisage the diversity of the ancient world. I was taught Classics the same way as white classicists, by white classicists and with material written and prepared by white classicists. The problem is endemic, so endemic that classicists of color can end up making the same assumptions and mistakes as white scholars. I made the same mistake with art, unable to see myself in those ethereal beauties that the artists had held in such high-esteem – or in the artists who painted them. Lizzie Siddall, artist in her own right and wife and model for Rossetti, flame haired, pale skinned and slender, didn’t reflect me at all.

But it can be done. I fell back in love with the Pre-Raphaelites when I found Rossetti’s paintings of the voluptuous Fanny Cornforth, Burne-Jones’ paintings of his Greek mistress Maria Zambaco, and later, the paintings by various artists of the mixed-race Fanny Eaton. In same way that Shelley P. Haley rewrites the Moretum with a black feminist translation in her essay on black feminism and classics, so we can do the same with the story of Pygmalion and his statue. We can find positive diversity without a mirror. I can’t rehabilitate the statue’s autonomy, but I can restore her color, and the color of the Classics. Classics, like ancient statuary, isn’t milky white. It is a riot of color, and it can let me in.

(Header Image: Terracotta polychrome head found in the Tiber and now at the Baths of Diocletian in Rome. Photo via Twitter by Prof. Emma-Jayne Graham).

Authors