Catherine Muñoz Arango

November 16, 2020

On November 3, 1903, the Department of the Isthmus separated from the Republic of Colombia and became its own republic. This act ended 82 years of history between them. The reason? to allow the US to build a canal after Colombia refused to in August of that same year.

The new republic entered the twentieth century with great emotion and with the dream of finally seeing an interoceanic canal. New projects were sought, but there was also an uncertain future accompanied by the first conflicts with the Canal Zone and the United States. Which were initiated by the Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty of 1903, as in Article 1 indicates that the US will guarantee the independence of the Republic and the right to intervene in the affairs of Panama as it is set forth in Article 136 of the 1904 Constitution. The former raised doubts, and questions not only from the neighbors countries that said that Panama was now a US a protectorate and that in fact it was not Latin American, but also by the same Panamanians that felt that way and understood it as an attack on sovereignty and as a risk on the national identity and Panamanian culture.

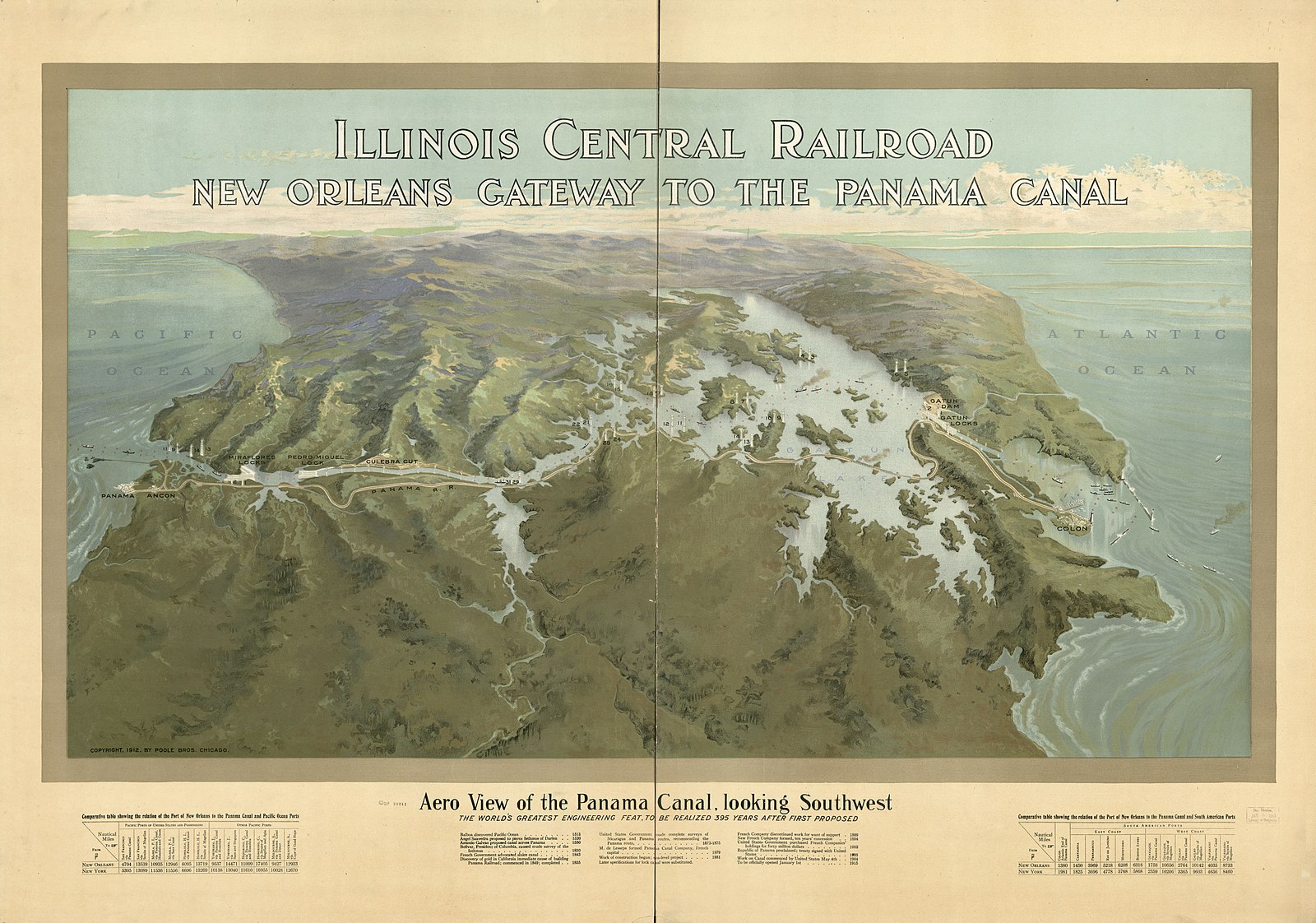

Figure 1: Aero view of the Panama Canal, looking southwest, 1912 (Library of Congress)

Now, what do Greco-Roman people have to do with the founding of a small republic in 1903? And what is it to do with the current moment in Latin America, where we are asked to study our history from non-European concepts and positions? The answer to the first question is that there were Greeks and Romans in Panama, obviously not alive in flesh and blood, but alive through their writings and their thoughts on the first governments. The second answer, in my opinion, because it is still valid to study Panama from different angles and not just only from its political history.

Since the 19th century, Greeks and Romans had become a part of the ways in which the Panamanians sought to understand themselves; from the Gold Rush to the discussions of the canal treaty with Colombia. We can even point to the fact that the Greco-Roman reception appears even before the separation of 1903. It was used as an instrument for politicians to make stronger messages even then.

The Panamanian liberal leader, Belisario Porras (who was 3 times president of Panama), in July of 1903, remarked on how dangerous the ratification of the treaty with the United States would be, because that would allow them to perpetuate their presence in the isthmus. For that reason, he compares them with the monsters found by Odysseus upon his return from Troy, simply to highlight what would be the fate of the Isthmus if Colombia if they accepted the Herran-Hay Treaty:

It is seen, then, that we are placed as the navigators, persecuted in Neptune in Homer's Odysseus, between Charybdis and Scylla; exposed to succumbing between the dens, like the jaws of one of the two mythological monsters. [1]

The strongest use of the Greeks and Romans is seen in terms of the Panamanian national identity. After 1903 the citizens of this new republic had to be Panamanian, but they did not know how, much less how be a good one. They sought to base this new identity in the classical world, since to their minds, anything else is better that being Colombian or American. This process has a parallel in the Creoles of the old Spanish viceroyalties of the 19th century. After their independence, the new republics denied their Spanish origin and sought to identify their origins in Greece and Rome, preferring the classical world as a political and cultural model.

Figure 2: Coat of arms of the Republic of Panama on a green background (Wikimedia).

In the same way, Panama looked to a classical exemplum, starting after 1904 until around the 1940s. The ideas, concepts, and iconography in Panama became Greco-Roman, and this had repercussions on the formation of a Panamanian national identity. This can be seen from the paintings to the symbols of the nation, such as in the Coat of Arms (fig. 2) with its motto in Latin, Pro mundi beneficio ('For the benefit of the World'), [2] even in educational projects.

Classical reception was seen in the new architecture as well. Panamanians first began to build in neoclassical styles such as the Municipal Palace (fig. 3), the Saint Thomas Hospital, the National Archives (fig. 4), and the National Theater or the National Institute. The latter is important, because it was the first high school founded after 1903. It later became the center of the protests for the sovereignty and recovery of the Canal. In a symbolic way, it is significant because its neoclassical façade contrasts with the austere buildings that border the Canal Zone.

.png)

Figure 3: The Old Municipal Palace, Panama City, Panama (Wikimedia).

The search for a new identity with antecedents in a classical model was most seen in the reception of the ancient world that politicians, poets, and educators drew upon. Socrates, Plato, Pericles, Hannibal, Thermopylae, Leonidas, Aristotle, Seneca, Sparta, concepts such as good, laws, and lady justice (or Motherland), were part of how the ancient world was used to establish a national identity and influence the formation of the Panamanian citizen.

The clearest of examples, can be seen in the poet and liberal politician Guillermo Andreve (1879-1940) who, from his magazine, El Heraldo del Istmo (1904), shared and published poetry, stories, speeches, and letters from various important figures of the Panamanian politics. He also publsihed writers, who had concerns about how to be Panamanian. These writers were not afraid to mix nationalism with references to antiquity. It was as Minister of Education (1914-1916), during Belisario Porras' first presidential term, that Andreve managed to make project the classical world onto Panama.

Figure 4: The National Archives, Panama City, Panama (Wikimedia).

How do you manage to bring concepts from the 5th century BCE to a small country that just started to build schools and is graduating its first teachers? Through small references, fragments of Greek philosophers, or references to mythological heroes where certain qualities and values are highlighted. In that way, Andreve transmitted to the students the practices and models that they should replicate. Those students that Andreve spoke to, in his estimation, should have a national culture and develop civic values to wrestle with the influence of the United States. And of course, what better models than Socrates or Leonidas?

Andreve mixed in Socrates, Augustus, Leonidas, Athens, and Sparta into his speeches to Panamanian students, so they could learn patriotism and conjure a love for their Motherland as the Greeks did thousands of years ago. He also discussed the importance of the patria ("homeland") for a Roman citizen, because in his mind the students that lived with the US occupation must developed a love for the country and a respect for the laws.

This can be glimpsed at in a short speech, "Amor a la patria” (Love to the country) (1921), where he pointed out the importance of cultivating civic values:

There is in the depths of the human heart a great feeling that inspires all generous actions and all noble sacrifices. It is this feeling that inflamed Leonidas' chest and decided to sacrifice himself to the thrust of the Asian crowds; that he made Hannibal take his life since he alone was the only hindrance to Carthage's happiness; that he forced Solon to embark for the unknown in order for Sparta to preserve the laws that made it powerful. [3]

In the same way, Andreve wished to develop a national conscience and feelings of attachment in order to create a responsible citizen. He believed that otherwise, the story of Pericles and Athens would be repeated:

Pericles did not avoid the misfortunes of Athens despite its splendor and its greatness, because it did not cultivate civic virtues in its inhabitants. Rome declined and saw its power roll to the ground when the patricians and matrons abandoned their austere customs and Asian vices flourished on the banks of the Tiber [4].

After the significant focus on classical antiquity, we do not know in what moment its ideas and speeches started to lose importance and currency in the Panamanian Society; however, we do know that after the second half of the 20th century their were fewer mentions and references to the classics in political rhetoric. Few people today remember that at one point in our history, someone described the Panamanians as people with a potent mix of ancient and modern ideals.

...the heroism of the Spartan people, the culture of the Athenian, the patriotism of the French, the courage of the Roman [5].

[1] Belisario Porras, “Reflexiones canaleras o La Venta del Istmo”, Revista Cultural Lotería, n. 373 (1988): 89

[2] Ana Elena Porras, Cultura de la interoceanidad. Narrativas de identidad nacional (1990-2002), (Panamá: Instituto de Estudios Nacionales, Universidad de Panamá, 2009), 212.

[3] Guillermo Andreve, “Amor a la Patria” en Ideario de don Guillermo Andreve, ed. Ministerio de Educación de Panamá (Panamá: Centro de Impresión Educativa, 1983), 14

[4] Guillermo Andreve, “Amor a la Patria” en Ideario de don Guillermo Andreve, 16.

[5] Guillermo Andreve, “Amor a la Patria” en Ideario de don Guillermo Andreve, 17.

Authors