Danielle Bostick

April 21, 2021

When I came back to the classroom in 2016, after an interlude career as a mental health counselor, I noticed systemic problems in the field of Classics that I had previously normalized. At the pre-collegiate level, Classics is not only elitist, but also exclusive in a way that has made it a racialized space. Mock slave auctions, for example, were held as fundraisers under the Junior Classical League brand as late as 2019 and still have not been formally banned. Instructional materials present slavery with the same rhetoric as Lost Cause white supremacists. At the JCL convention this year, the piece for the boys’ dramatic oration was a selection from Ars Amatoria, and the theme for the “couples costume” contest regularly involved rapist-victim dyads.

There are larger issues at play, as well. For example, Latin is often treated as an honors course, a practice that situates it in a larger, segregated system. Since the practice of tracking based on perceived ability places Black students in lower levels disproportionately, treating Latin as a pre-collegiate course serves as a layer of racialized gatekeeping. (For more about tracking based on perceived ability, check out Keeping Track by Jeannie Oakes.) Access to Latin is also restricted for other reasons. It is often offered in high-end private schools with reputations for placing students at the most competitive universities in the United States. The ten high schools with the highest number of students accepted to Harvard, Princeton, and MIT all offer Latin. The average percentage of Black students in these schools is just five percent. National Latin Exam scholarship recipients from the years 2017, 2018, and 2019 have attended high schools whose average percentage of Black students is also just five percent.

The culture of secondary Classics doesn’t just affect high school Latin students. It affects the state of Classics in post-secondary institutions, too. In a 2019 report on harassment in post-secondary Classics, only 0.9% of survey respondents identified themselves as Black or African American. More broadly, the culture of secondary Classics informs perceptions of Classics outside of academia. People who have never studied Latin assume that it is for elite, white students. When I tell people I teach Latin in a Title I public school, the response is always one of surprise.

While pushing for systemic change within pre-collegiate Classics, I have had hundreds of interactions with organizations and individuals in the field. Through these interactions, I have noticed a distinct aversion to addressing historic, systemic failure, frequent diversions to classroom-level issues. For example, I have frequently encountered defenses, justifications, and general indifference around practices like mock slave auctions and rapist-victim-themed costume contests. In recent years, there have been a lot of statements released related to social justice, but in the case of secondary Classics, these messages have not resulted in concrete action or widespread engagement with these issues. For example, when the ACL condemned slave auctions, they stopped short of an official ban. As Aidan Gregg, a high school student and JCL officer noted, “There has been no meaningful reckoning for these events. Instead, they have been scrubbed from public memory.”

When I write and present about these issues, I intentionally do not mention specific details about my own program. My students are in my classroom to learn Latin, not become case studies in a presentation. Inside and outside the field, there are also plenty of educators and other experts disseminating ideas about the nuts and bolts of equitable, ethical teaching. Mostly, though, I avoid talking about the classroom because systemic problems require systemic solutions. This is not a problem that we can fix one classroom at a time. The entire infrastructure of Classics needs to change.

Recruitment and marketing are two of the most common themes that have emerged in my conversations with other people working in Classics about classroom- and department-level solutions. Here are two common myths that maintain Classics as an exclusive space.

Myth #1, Recruitment: Diversity and inclusion will increase enrollment and save the field

Low enrollment is certainly a collateral effect of Classics’ history of racism and elitism. Within the field, diversity and inclusion are often presented as ways of building programs and saving the field. The logic behind this way of thinking is problematic: “We can no longer survive by existing for white, elite people. Now it is a matter of survival to welcome the people the field has historically excluded.” The late Derrick Bell called this phenomenon interest convergence. In the context of Brown v. Board of Education, Bell theorized that self-interest is the impetus for white people taking action against anti-Black racism. The field has certainly approached racial justice from a starting point of self-interest, whether it has been to increase enrollment or to maintain a positive public image.

When I started at my current school in 2016, I had six students in my Latin I class. This year, close to 45% of incoming freshmen chose Latin as their elective. (I could only accommodate 100.) My program is also much more diverse than it was in 2016, when almost all of my students were white and considered “pre-collegiate.” Today, my program mirrors the demographics of my school community.

I did not make my program inclusive in order for it to grow. My program grew because I made it inclusive.

Children are required to attend school until they are 18. And they are often required to attend a specific school. Equal access to education in this context is a civil right, not an option. Access to Latin should therefore be open to all students. At a bare minimum, that involves removing institutional barriers to accessing courses and content. While conditions are different at post-secondary institutions — since they are selective by nature and students are there by choice — the crisis in Classics is not a question of marketing. It is a question of ethics. In the absence of a cultural shift, diversity is numerical, and inclusion is nominal.

Myth #2, Marketing: We need to articulate and advertise the value of Classics.

Classics has long been obsessed with its value and relevance. In 1917, Andrew West worried Classics would be “relegated to an unimportant place in the curriculum.” Today, the continued survival of Classics programs has been linked to value and relevance — as if the future of the field depended on effective marketing. Part of the mission of the Society for Classical Studies is to advance the “enduring value” of Graeco-Roman antiquity. The American Classical League “celebrates, supports, and advances the teaching and learning of the Greek and Latin languages, literatures, and cultures and their timeless relevance.” Other content areas do not focus on their value and relevance to this extent (or at all).

In Classics, value is key in answering questions of existential panic: Why are fewer people interested in Latin? What can we do to boost enrollment? Why is this happening to us? If we could only articulate the value of Classics, so many people would want to benefit from its study.

Classics has asserted its value and relevance in the service of racism and oppression. John Calhoun used proficiency in ancient Greek as a way to measure the humanity of Black people. Countless Americans, including Thomas Jefferson and Basil Gildersleeve, found value in Classics as a way to justify the institution of slavery. The alleged value of Classics has been as a marker of elite identity and tool of assimilation. Recruitment material produced by the National Committee for Latin and Greek presented Classics as a “shared heritage” that helps “bring students into the mainstream of American culture and western civilization.” Problematic marketing materials have been removed from the NCLG website, but their legacy persists. I stopped using NCLG marketing materials in 2016.

Prospective students need enough information about Classics to make a decision aligned with their strengths, values, interests, and goals. Providing that information involves shifting emphasis from the value of Classics to that of the individual. What are the student’s interests? What are the student’s goals? What are the student’s strengths?

A conversation about Classics should be empowering, instead of an opportunity to amplify students’ alleged inadequacies and create an unnecessary power differential. We have no business focusing on the “value of Classics” until the field has recognized the value of people. Focus on the “value of Classics” supplants the value of prospective students’ potential contributions to our programs and creates an unnecessary hierarchy from students’ very first encounters with our content area.

A focus on the “value of Classics” diverts from the harm that this purported value has inflicted in the American education system and, more broadly, society. Many problems at the post-secondary level have their roots in high school programs, and the way we represent Classics has an impact outside of the field. As we look at the needs and struggles of individual programs, it is important to work towards systemic change.

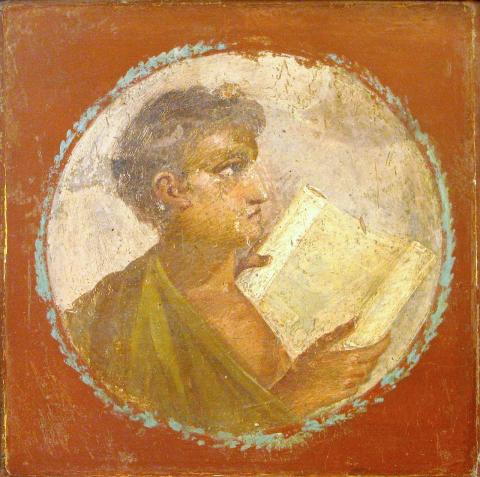

Header image: Roman portraiture fresco of a young man with a papyrus scroll, from Herculaneum, 1st century AD. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Authors