T. H. M. Gellar-Goad

January 12, 2021

Against the backdrop of the United States’ first non-peaceful transition of power, there is a much smaller-scale — and much more peaceful — transition happening: the changeover of the SCS Communications Committee chair and SCS blog Editor-in-Chief. Sarah Bond, after three years of visionary leadership and fantastic direction of the blog, has handed the reins over to me, as a veteran Committee member. I think I speak for the Committee and for the blog’s readership when I offer Sarah my profoundest gratitude and appreciation for her awe-inspiring work during her term. I’ll be standing on the shoulders and following in the footsteps of a giant.

While I believe our SCS transition has been and will continue to be smooth — Sarah actually attended my inauguration, for one thing — the state of play in the nation’s capital is grim, with a failed white-supremacist coup and storming of the Capitol Building this past Wednesday (which pro-democracy House member Ted Lieu has dubbed Insurrection Day), and the looming threat of more violence to come, all instigated by outgoing President Trump and condoned or implicitly permitted by many elected officials of his Republican Party. Some members of Congress, having emerged from Capitol evacuation and lockdown and in the process of certifying the election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, invoked the unraveling of the Roman Republic — or, rather, following Harriet Flower’s Roman Republics, the transitional period between the collapse of the final Roman republic and Augustus’ consolidation of power — in decrying the violence earlier that day (e.g., in the mode that Colorado’s Senator Michael Bennet did). History professor Edward Watts, meanwhile, has compared last Wednesday’s events to the post-election violence surrounding Marius, Glaucia, and Memmius in 100 BCE.

Figure 1: Proud Boys marching in front of the U.S. Supreme Court along First Street between Maryland Avenue and East Capitol Street, NE, Washington DC on Wednesday morning, 6 January 2021 by Elvert Barnes Photography (Image via Wikimedia under a CC-SA 2.0).

I find myself thinking back to the not-quite-halcyon days of 2014, when the former American Philological Association had just donned its current name, and Texas Senator Ted Cruz was rehashing Cicero in a speech on the Senate floor. Cruz, angered at then-President Obama’s announcement that he would undertake some limited immigration reform measures by executive action, delivered a close adaptation of Cicero’s famous first oration against Catiline, using, as far as I can tell, the translation available on the Perseus Project, with Obama in place of Catiline. The situation then was, however, substantially incomparable to the Catilinarian conspiracy, as noted by political observers at the time, including even the conservative National Review. At the time, classicists Jesse Weiner, Duncan MacRae, and Jason Schlude (as co-author with classics students Sarah Evans, Hunter Huntoon, and Michael Macken) discussed Cruz’s distortions of the original and the troubling subtext of violence in the allusion — since, after all, Cicero was proposing the extrajudicial execution of Catiline. More recently, Beth Eidam, a recent Dickinson College classical studies alum, pointed out that Cruz seemed not to have thought about how the aftermath of the crisis of Catiline played out for Cruz’ role model Cicero.

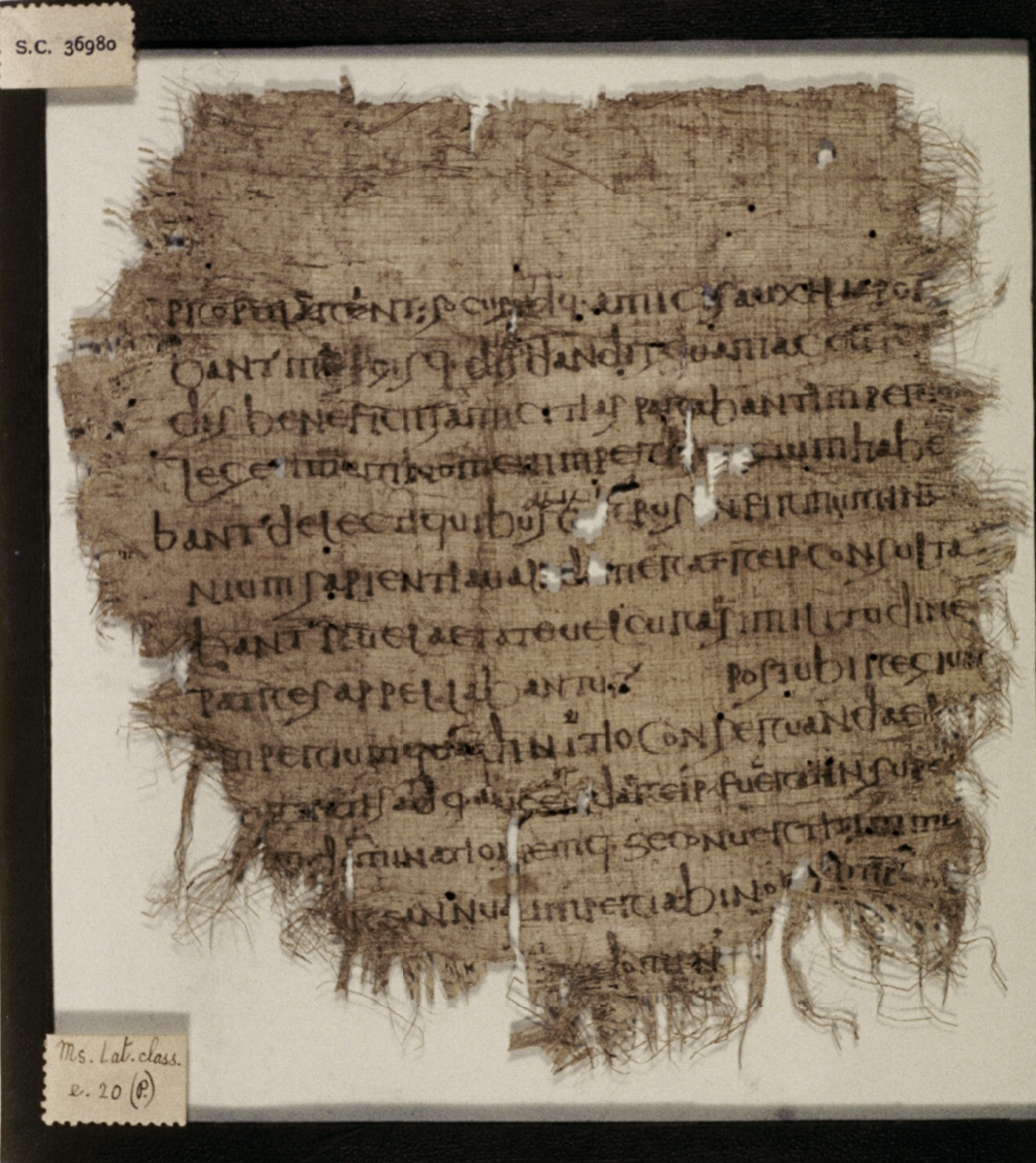

Figure 2: Papyrus fragment of Sallust, Catiline, 5th C CE Fragment of Chapter VI. Papyrus codex found at Oxyrhynchus, written in early half-uncial script (Image via the Bodleian Library under a CC-BY-NC 4.0).

But now, in 2021, Cruz is on the other side of the law –– and the Republic. The failed coup in Washington has some — limited but germane — parallels with the Catilinarian conspiracy: a disaffected losing candidate for highest office (Trump, Catiline); claims of election corruption (totally unsubstantiated in the case of 2020); property destruction (the Catilinarians were planning to set fires throughout Rome); illegal possession of arms in the city; and, in the wake of the failure to overthrow the government, complicit senators eager to distance themselves from the leader of the sedition (Bestia, Cethegus, Lentulus, Longinus, Hybrida: we’re looking at you). One of the latter-day senators is Cruz himself who, along with senators such as Josh Hawley, supported the efforts to subvert American democracy, even fundraising during the siege of the Capitol itself, before making an about-face once he realized the tides had turned against the effort.

I teach the crisis of Catiline each fall in my first-year seminar, using Bret Mulligan’s fabulous Reacting to the Past game of the same title. It is a great way of exploring the potential fragility of political systems governed by deliberative bodies, the many ways shared governance can fail when even a minority of its participants rescind their consent to be governed. Something I’ve increasingly been asking of myself and my students is to think about ourselves and our own society and our own political moment as we roleplay Cicero and Caesar and Crassus and Clodius and all the other stakeholders in the Catilinarian conspiracy, regardless of whether there’s a C in their name. How will we know, I wonder, whether we are, like them, in a post-republican period of transition, without realizing it ourselves? Cruz and Catiline, his conspiracy, and the Capitol coup refresh this question, make it pressing as never before. (As one of my alums wrote me on last Wednesday night: “THM, I’m not pleased that the national news looks like the Rome game in FYS.”)

Figure 3: “Roman propaganda cups, 1st century BC(E), from Museo Nazionale Romano - Terme di Diocleziano, Rome. These cups, filled with food or drinks, were offered in the streets in occasion of the elections; the cups had the name of a candidate engraved. The cups depicted were produced for 63 BC elections for 62 BC. With the cup on the left, Marcus Porcius Cato (Cato the younger) asks (petit) to be elected Tribune of the plebs. The cup on the right was sponsored by Lucius Cassius Longinus (praetor with Cicero in 66 BC) to support (suffragatur) Lucius Sergius Catilina (Catilinae) bid for consulate” (Caption and Image from Wikimedia under a CC-SA 1.0).

Although historical comparanda may be compelling, we must remember, alongside our stalwart emeritissima Sarah Bond, that we are not Rome. We should absorb the careful and persuasive arguments from scholars of U.S. history and politics that the Insurrection Day attack on the Capitol was more like a lynch mob (or the 1898 racist coup in Wilmington, NC) than a Catilinarian conspiracy. And we must grapple with the fact that some of the white-supremacist insurrectionists cloaked themselves in classical references, such as Roman laurels or “Come and Take It” flags or faux centurion helmets.

But something that the disciplines of classics, classical archaeology, art history, and ancient history (among others) offer us is the lesson that cautious, nuanced thinking about how crises have been handled in other times, places, and cultures can help us as we respond to our own. As James Baldwin noted in The Price of the Ticket:

You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It [was books] that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.

And that is one of the things I am confident that the contributors to this blog have offered since its inception in 2013 and will continue to do in the years ahead. I am thankful for the tireless efforts of Sarah and our outgoing Communications Committee members and Associate Editors Sam Flores, Adrienne Ho Rose, Elizabeth Penland; our continuing members Dani Bostick, Patrick J. Burns, Wells Hansen, Arum Park, and Christopher Polt; our new Assistant Editor Tori Lee; and incoming members and Associate Editors Rosa Andújar, Bethany Hucks, Ky Merkley, and Christopher Waldo.

As we move into new era for the blog (and for the United States), I encourage each of you to think about what you might have to say and share with our readership. Write for us! You can send us a pitch any time — and we want to hear what’s on your mind, whether as a contributor or simply as a constituent of our classics community.

Authors