Molly Ayn Jones-Lewis

July 10, 2023

“Do you know what Romans used to clean wool?”

Wait for disinterested shrugs. Pause for comedic timing.

"Human urine!”

Enjoy the horrified gasps. Cue images of a Roman fullonica.

All I wanted when this began was to make sure the spinning demonstration I give in my Roman World class accurately showed how Romans spun thread. I’ve been a hand-spinner since college, when a nice lady sold me a very bad modern spindle and gave me a ten-minute lesson. Fiber art has been a source of sanity and peace to me over the years, a medium that fulfills a deep need for soothing sensory input and offers a productive use for my fidgety hands that never know where to put themselves.

But most fiber artists are not professional historians, and few historians have processed fiber. Most historical research crafting is focused on the medieval period. Ancient specialists focus further along the production line when talking about the mechanics of creating cloth. If you’re a unicorn academic who processes Roman wool from sheep to cloth, please email me, because I need you.

I am no expert on historical textiles, so do forgive any ignorance forthcoming. I tried my best to find guidance when I decided to shift my modern spinning setup to a correct Roman version, but the literature I dredged up was not at all specific in the ways I needed it to be. I got a local experimental archaeologist to kindly make me a ring distaff and spindle sticks, scored some ancient whorls from our department’s collection of bric-a-brac, and then proceeded to gather every image of spinning art I could google. From my work on ancient medicine (my real specialty), I knew where to find information about wool, but the description of what, exactly, to do with it was something short of helpful.

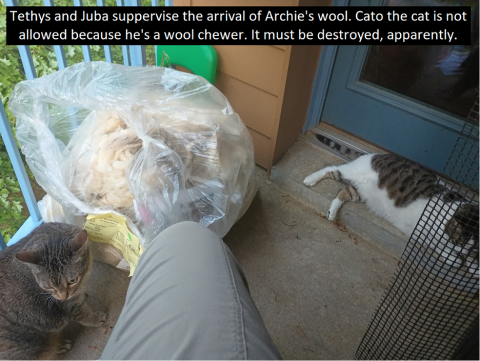

So I did the only reasonable thing and began several years of experimental archaeology that have now arrived at the inevitable conclusion to this adventure: several jars of my long-suffering spouse’s urine, disjointed passages ranging from Aristophanes to Pliny the Elder, and seven pounds of fleece from a sheep named Archie. My supply chain for this project is aggressively personal.

Let us pause for a moment to orient ourselves to the steps of turning sheep fur into clothing:

- Shear sheep.

- Remove as much poop and vegetation as possible. Lysistrata also wants us to hit it with sticks, but I find that this step only felts the grass and dirt more firmly to the wool. I begin to suspect Aristophanes skimped on his research.

- Clean lanolin, sweat, and dirt off fleece.

- Optional: dye fleece. If purple, feel bad for wasteful luxuria and question your masculinity on the way to the bank.

- Dry fleece (direct sunlight will bleach it).

- Comb fleece in the arrangement that will work best for the distaff you’re using.

- Put wool on distaff, spin onto spindle. This is where fluff becomes thread.

- Weave until it’s cloth.

- YOU ARE NOT DONE YET because you beat the cloth up to make the fibers “bloom” into cloth you can’t see through. We call this “fulling.” This is the part where urine is definitely involved.

- Stretch wet cloth before you dry it if you want it to be unfelted.

- Profit!

Step 11, by the way, is the important part for fabric workers (mostly women) in the ancient world. This labor created income for her and her household. We are making an error when we shrug it off as gendered labor meant as sexist busywork, or address only the injustice of forcing femmefolk to do fabric labor without acknowledging the major contribution it presented to the ancient economy. This sector of production, especially the early stages (1–3), were both a potential source of economic power to disempowered people and a part of the supply chain neglected, though not ignored, by our elite source authors. That said, the fact that women could be assumed competent at woolwork also motivated human traffickers to enslave them.

Ovid’s Arachne was a peasant.

This, in a nutshell, is the problem I had run straight into. My sources were not telling me how to turn Archie’s lovely, crimpy wool into distaff-fuel because they were rich dudes. Dioscorides — possibly a military physician, and more hands-on than most — comes closest to helping me out when he explains that lanolin, the oily wax that sheep excrete, can be harvested only if the wool is not washed with soapwort first. Not urine, but soapwort. He also mentions hot water’s ability to separate lanolin from wool while leaving both products usable, but he is far more interested in lanolin, being a pharmacist. As of now, I’ve yet to find an ancient literary passage explicitly suggesting urine at step 3 in this process. Pliny, alas, only brings in urine at step 4 (dye).

This lacuna in the written record came as a shock, and not just because I had already done the awkward work of getting my spouse to pee in a set of mason jars for a week. In later times, urine was one of several go-to options for dissolving the waxy, hard, sticky lanolin off wool. While it is possible to spin without removing lanolin (we call this in-the-grease), it is not easy, because the tips of the fleece are stuck together by it, like this:

If you want to comb the wool, you either need to heat your metal combs or remove the lanolin first. Hot water will float the wax to the top of the pan, but hot water plus motion causes the wool fibers to felt into a mass, so you must take care to keep the locks as still as possible. Soap lifts grease at a lower temperature, neatly solving the heat problem. Today, we use harsh detergents. Dawn dish soap is a classic choice for spinner on a budget. Romans used soapwort for sure, and likely urine too. Urine is much easier to get than soapwort and was also the cleaner of choice for finished wool cloth. I think it’s reasonable to include it in my range of options.

Spinner friends begged me to just use the detergents. Even my historical spinner friends were horrified that I was actually going to try it. “You’re so brave,” said all two of them. But no, now I was in too deep, and I had to test the claim I was finding in experimental archaeology projects like this one. And this and this.

I did have success cleaning fleece with just hot water baths, but it used more water and fuel than would have been profitable for an ancient wool producer. I have indoor plumbing and a water heater, but people who were not Livia Augusta would have struggled. Besides, you’re all here to find out about the urine, so let’s move on to that part, shall we?

Do the breakdown products of human urine turn soapy in the presence of lanolin well enough to clean a fleece? And can I manage to do it on my back porch without getting evicted from my apartment?

Fortune favors the bold, as Uncle Pliny tells us. And I don’t have any soapwort.

Tradition has it that people with lots of testosterone make better detergent urine, though I haven’t got around to proving it (yet). To be frank, between my spouse and me, one of us can aim into a jar better, and it is not I. He also tends to develop kidney stones, which I took to be a positive sign for the oomph of his urine. Perhaps I have been around my source material too long. Ah well. Six mason jars are enough to fill a small tub, and I waited patiently for them to…mature.

How do you know when your pee jars have sat long enough? Olfactory, my dear Vespasian.

Next, the exciting part. Lanolin and suint (salty sheep sweat) meet stale urine, and allegedly the magic ensues!

I was shocked to find that within an hour of placing the raw wool into the urine bath, the acrid odor of poorly cleaned urinal stalls had dissipated, replaced by a normal aroma of wet sheep. Again to my shock, dirt released from the wool just as quickly as it had when I was using modern detergent. My neighbors remain blissfully unaware.

Those brave modern souls who have embarked on this adventure usually boil the urine and wool within 24 hours of the cool soak. However, I have a lease to protect and my spouse said, “No. Not in my kitchen, you don’t. I draw the line at pee on my stove.”

And really, this suited my purpose of keeping fuel expenditure to a minimum. If urine cannot act as a detergent without heat, then how useful is it to a premodern launderer? I persevered.

By “persevere,” I mean to say I let the vat of pee and unwashed wool sit covered on my porch for three days. Even as the ancients foretold, the urine had done its twin duties: reacting with the waxy, oily lanolin and producing a smell of indescribable pungency.

Let me attempt to describe it. Even if you aren’t interested, your class will ask nonetheless. It’s not the smell of a summer camp outhouse or the urinal of someone with faulty aim, though there are notes of outhouse present. However, the most notable component is ovine, an intense concentrate of the most off-putting elements of wet wool odors deepened with the bite of dungpile. It’s intensely agricultural and doesn’t immediately bring on my aversion reflexes. It hasn’t the ammoniac quality of cat accidents. I’m used to sheep smells, and I find it much more tolerable than I find the perfume counter at Macy’s, home of the speed migraine.

I hope that clears things up.

While I can’t photograph the smell, I did capture the visual change fairly well! Note the gelled luster and cloudy appearance of the liquid in the tub, and you’ll see the important benefit of this whole unpleasant process. The lanolin has left the wool and bound with the urine, and the two have combined to form something promisingly like liquid soap. We are ready to rinse the unpleasantness away and reveal the clean wool beneath.

I replicated the traditional rinse in a stream with 20 minutes in a cold shower, then did an extra cold water soak because my cringe response was beginning to overcome my methodological rigor. There was a worrying waxy residue coating the mesh bags, and the smell was not entirely gone from the fiber. I admit, my resolve was sorely tested and I eyed the modern detergent on my way back to the porch to put the (hopefully) cleaned wool into the crisp outdoor air for the final step, drying in full sunlight to bleach out the staining and remove the odor.

While it dried, I ordered a bag of soapwort off the internet. Dioskourides might have been right after all when he overlooked urine for a step 3 cleanse.

I was underwhelmed with my final results. The lanolin had only partly dissolved, leaving the wool stickier than it had been raw. I could barely comb it. I hated my life. I may have cried a bit at my ruined ounces of wool as I tried to force my combs through it. If I were processing a finished cloth, this would have been perfect! The fibers dried fluffy, soft, and stuck to each other — exactly what you want at the fulling stage.

The soapwort, sold to me by a lady who claimed it would banish curses and ward against evil, arrived in a baggie. I can’t speak to the amount of evil on my sheep, but it did a great job at banishing the lanolin overnight. It smelled great. The wool combed out into a glorious floof that flew off my distaff with barely any effort on my part.

Friends, I should have listened to Pliny and Dioskourides.

So what have we learned?

Don’t put pee on your wool until after it’s combed. But pee does, indeed, remove grease and fluff wool fibers.

If Dioskourides tells you to do something, do it. Well, don’t put dung onto wounds or rub used olive oil scraped off an athlete for your anal fissures. But he was right about the soapwort.

Authors