Eleonora Colli

January 30, 2020

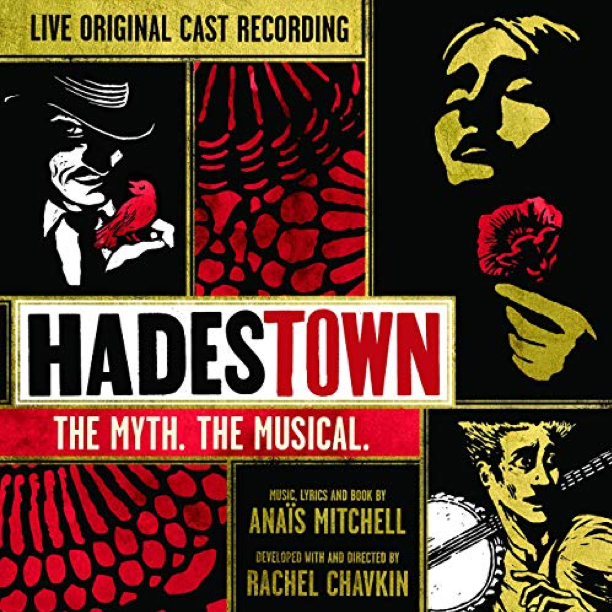

The tale of Orpheus and Eurydice has long been a popular myth in music, drama, literature, and film. Anais Mitchell’s recent musical sensation Hadestown (which was workshopped from 2006 and had an off-Broadway debut during the 2017-18 season) is but one example of the reworking of the legendary love story. Although Mitchell’s musical is broadly defined as a folk opera, it is just the latest instance amongst many pop culture reinterpretations of the Orpheus myth across different musical genres. The tragic tale of a famed musician who traveled to the underworld to retrieve his love from the grips of death has inspired several musicians during the 1990s and the 2000s. Many of these retellings have engaged with one of the most important themes of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth: the power of music and art to provide salvation.

In addition to salvation, these reworkings often underscore the innate power of art and the artist across different political moments and for different collective and personal purposes. Mitchell’s opera, and particularly Hades’ song “Why We Build The Wall”, have been recognized for their political relevance in our current times,[1] but many pop, punk, or rock albums similarly deal with representations of the underworld. These more personal musical retellings, however, are generally preoccupied with the artist’s private history of failing and eventual salvation, turning the myth into an extremely personal narrative of self-discovery. As both creators and recipients of music, artists often play not only Orpheus’ role in writing and spreading their song, but also that of Eurydice, in benefitting from music’s salvific quality.

The dual role of the artist as both Orpheus and Eurydice in popular culture is particularly interesting when looking at the role of pop culture within society as a whole. In her essay “Image, Body and Performativity: The Constitution of Subcultural Practice in the Globalized World of Pop,” Gabriele Klein states, “pop as a way of living means a way of thinking and feeling, of living and also of dying’: to him, ‘it is for this reason that the mystification of an early death is an important element of pop culture.”[2] For pop music and pop culture to be totalizing in their effect, they have to portray both a way “of living and also of dying”, in order to bring together the portrayal of the artist as simultaneously victim and savior.

To fully convey this dual personality while representing the experience of death on stage concert goers, artists have often relied on alter-egos. Rocker Alice Cooper’s stage persona in Welcome to My Nightmare is perhaps one of the most memorable examples. In employing this strategy, music not only becomes a process of self-salvation and discovery, but ultimately reveals to listeners that the alter ego and thus the artist as Eurydice can be left behind for the Orphic experience to be completed, letting the artist arise as new. The death of the alter ego on stage symbolizes the revival of the artist in a different incarnation and turns the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice from a failing tale of caution to one of success.: the death of the alter ego, then, does not translate to the death of the artist, but to their renaissance.

It is no coincidence that the mythology of one of the most famous alter egos of all music history, David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust, ends with a song titled "Rock ’N’ Roll Suicide." Bowie’s comments on the meaning and visual performance of the song and of Ziggy’s story are also quite significant:

When the infinites arrive, they take bits of Ziggy to make themselves real because in their original state they are anti-matter and cannot exist on our world. And they tear him to pieces onstage during the song 'Rock and Roll Suicide.’ As soon as Ziggy dies onstage, the infinites take his elements and make themselves visible.[3]

Ziggy’s death as he gets torn to pieces is reminiscent of Orpheus’ destiny, mutilated by the Maenads:

membra iacent diversa locis, caput, Hebre, lyramque

excipis: et (mirum!) medio dum labitur amne,

flebile nescio quid queritur lyra, flebile lingua

murmurat exanimis, respondent flebile ripae.[4]

The poet’s limbs lay scattered all around; but his head and lyre, O Hebrus, thou didst receive, an (a marvel!) while they floated in mid-stream the lyre gave forth some mournful notes, mournfully the lifeless tongue murmured, mournfully the banks replied (trans. Jacoff).

While Orpheus encountered his death and kept singing only in the underworld, Bowie’s survival over Ziggy and the infinites’ ability to materialize themselves through Ziggy’s death indicate a survival of the artist, It also symbolizes the power of art and song beyond the life span of the alter ego. Songs can continue to save us long after mortal singers die.

Figure 2: Flowers and Ziggy Stardust depiction at the Bowie mural in Brixton, London (Image under a CCO via Wikimedia).

A similar feat is performed through My Chemical Romance’s most famous album The Black Parade (2006). The rock opera centers around the character of ‘The Patient’ and his passage out of life. It operates around the concept of the alter ego to fully convey the power of music and of the artist in their journey across the underworld. As a tale of life and death, The Black Parade again relies on the concept of the alter-ego and considers the question of art as a process of discovering self-salvation, It portrays the artist as preoccupied primarily with art as a tool for self-preservation. The band’s front-man and lyricist Gerard Way adopts throughout the album many different roles. As both storyteller and character, he narrates his relationship with art and music: the alter-ego of The Patient allows him to incarnate both Eurydice, in his questioning and assessing the failure of art, and Orpheus, as singer and story-teller, in the final re-evaluation of the power of music.

The core value of art is often questioned throughout the album by using the underworld and the struggle against death as a metaphor. At the end of the album, art is finally reconsidered as a method for achieving acceptance, discovery, and salvation. The alter-ego, in its ability to bring together and reconcile both Eurydice and Orpheus, is left behind in the underworld, so that the artist as a successful Orphic figure can re-emerge into the mortal world. This is proven in the lyrics to the final song of the album: "I am not afraid to keep on living | I am not afraid to walk this world alone | Honey, if you stay | I’ll be forgiven | Nothing you can say can stop me going home.”[5] The ending to The Black Parade argues for a hopeful reassessment of art as a tool for being one’s own savior.

Through the alter ego, the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice can be re-interpreted from a tale on art’s value to a tale of self-salvation and discovery. The failure of the alter ego does not then represent the failure of the artist, but instead provides cathartic experiences to audiences and the artist himself. Because of this focus on the potency and agency of the individual artist, the value of performance is further re-asserted and becomes more and more fundamental in making the audience convinced of the same salvific power of music provided by the performer for his or her listeners.

Cultural theorist José E. Muñoz addressed this aspect of punk-rock music specifically, noting this type of music can operate a particular “social choreography.” In his analysis of themes of annihilation and innovation in punk music, Muñoz “considers the desire, indeed the demand, at the heart of punk, for “something else” that is not the present time or place, with its stultifying limits and impasses. This demand is for a dystopia that functions like the utopian.”[6] His evaluation of punk-rock music centers around the concept of chaos as being generative rather than destructive, and further helps us re-frame the story of Orpheus and Eurydice as a hopeful tale through the employment of the alter-ego. The portrayal of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth as embodied in a dual self finds death in a dystopic underworld. In doing so, it also opens up a new utopia for both the artist and the audience. Modern musicians have today twisted the tale in order to have Orpheus learn from his mistakes: the artists’ re-birth on stage, then, sends a hopeful message to their audience: re-emerging from the dystopian underworld as a new and better self is possible.

[1]Cf. Claire Catenaccio, “'Why We Build the Wall': Hadestown in Trump's America,” SCS 2019 abstract: https://classicalstudies.org/annual-meeting/150/abstract/why-we-build-wall-hadestown-trumps-america

[2]Gabriele Klein, “Image, Body and Performativity: The Constitution of Subcultural Practice in the Globalized World of Pop,” in The Post-subcultures Reader, edited by David Muggleton and Rupert Weinzierl, pp. 41-9, (p. 42).

[3]Craig Copetas, “Beat Godfather Meets Glitter Mainman: William Burroughs Interviews David Bowie,” in The Rolling Stone. <https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/beat-godfather-meets-glitter-mainman-william-burroughs-interviews-david-bowie-92508/>

[4]Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book XI, lines 50-3.

[5]My Chemical Romance, "Famous Last Words," in The Black Parade (2006).

[6]José Esteban Muñoz, “‘Gimme Gimme This... Gimme Gimme That’ Annihilation and Innovation in the Punk Rock Commons,” Social Text 31: 3 (2013): 95-110.

Header Image: Orpheus with animals mosaic from Building A of the Piazza della Vittoria in Palermo, Sicily, Italy, 200-250 CE (Image by Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia).

Authors