Ana Maria Guay

December 13, 2018

A recent surge of critical focus on pseudoscience and classics focused on issues from Hippocrates and scientific racism to the racial bias of Ancient Aliens sees scholars doing the work to convince our field that classicists, historians, and archaeologists ought to take action to address the dissemination of pseudoscientific views in popular media.[1] Yet once we’ve accepted that we should confront pseudoscience in classics and archaeology, we find ourselves confronted with a rather different question: how can we best teach this in our classrooms?

When I was assigned as a teaching assistant for Intro to Greek Art and Archaeology last winter, I admit my first feeling was of slight trepidation: outside one requisite archaeology course for my bachelor’s degree, my classical training had skewed heavily toward philology and literary analysis.[2] How could I hope to leave a lasting impression on fifty students, with material I hadn’t “officially” studied in a course since my own freshman year, with only one fifty-minute discussion section per week?

Fortunate to be given reasonably free rein in the classroom, when I saw that students would be learning about the myth of Atlantis in lecture I decided to talk about the intersection between pseudoscience and archaeology. I knew most of my students, who were predominantly STEM majors, were not likely to become classicists. However, in giving them the tools to critique pseudoscientific and other bad faith uses of the ancient world—and more broadly, to recognize and evaluate the agenda of media in an age inundated with “fake news,” bad science, and conspiracy theories—I hoped they might leave the course with skills that would help them untangle disinformation wherever they went.

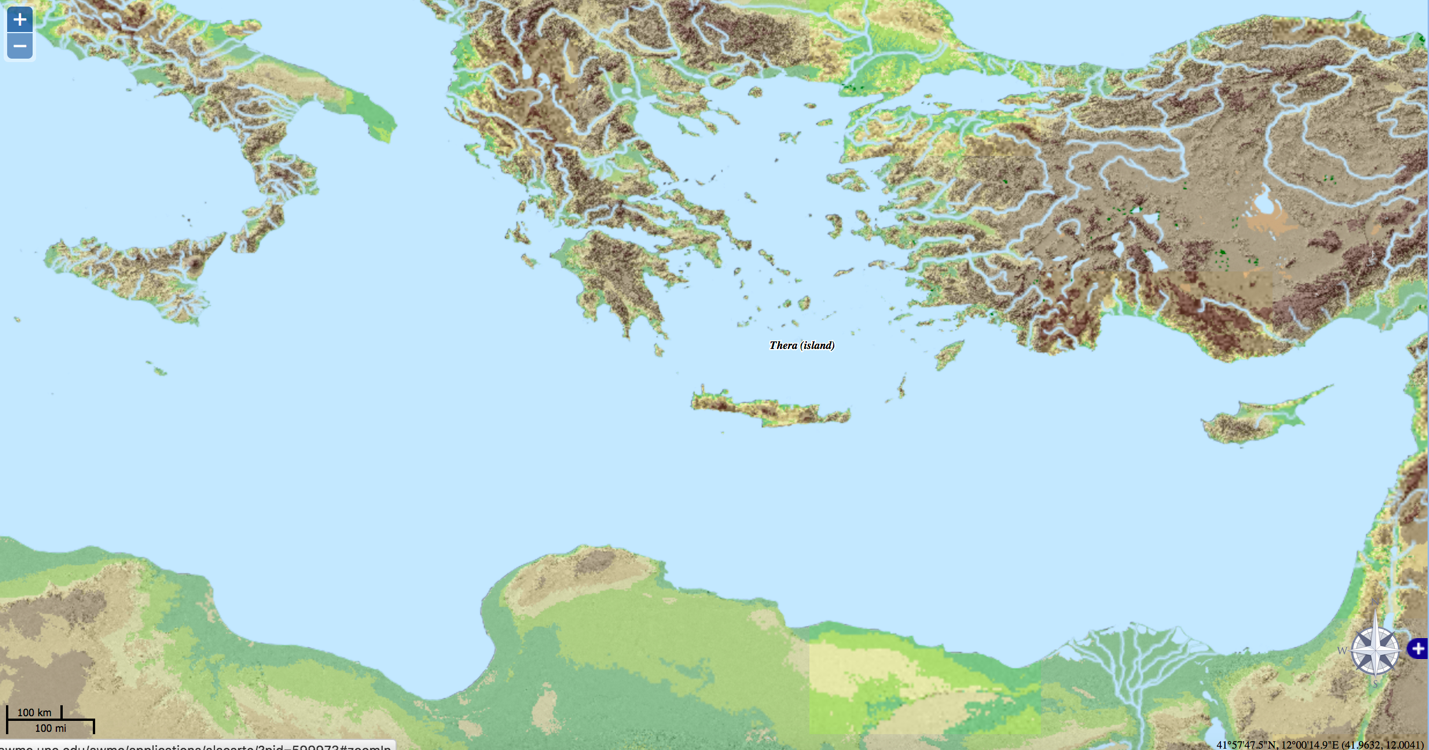

All students in the course had to read Plato’s account of Atlantis, in translation, from the Timaeus and Critias.[3] In my sections, we started by diagramming the qualities Plato ascribed to Atlantis on the board, then listing ways they did or didn’t match up with the archaeological reality of Thera (Akrotiri) students learned in lecture; we were universally delighted, for instance, by the idea of elephants on Atlantis, if not convinced of the reality.

I wanted to make sure most students knew both the basics of the Atlantis myth and the contents of lecture before getting down to serious analysis, even if they had skimmed the reading…or skipped the lecture. We also covered the important ground of determining that nearly none of my students had seen Disney’s Atlantis: The Lost Empire (2001), making me feel a little ancient myself.

I then asked students to close read the opening of Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, an 1882 publication credited as a main cause of popularizing the Atlantis myth. Donnelly, a populist senator from Minnesota, opens his book with a list of thirteen central propositions—due to time constraints, I gave students the first five, here, though I verbally summarized the last eight:

This book is an attempt to demonstrate several distinct and novel propositions. These are:

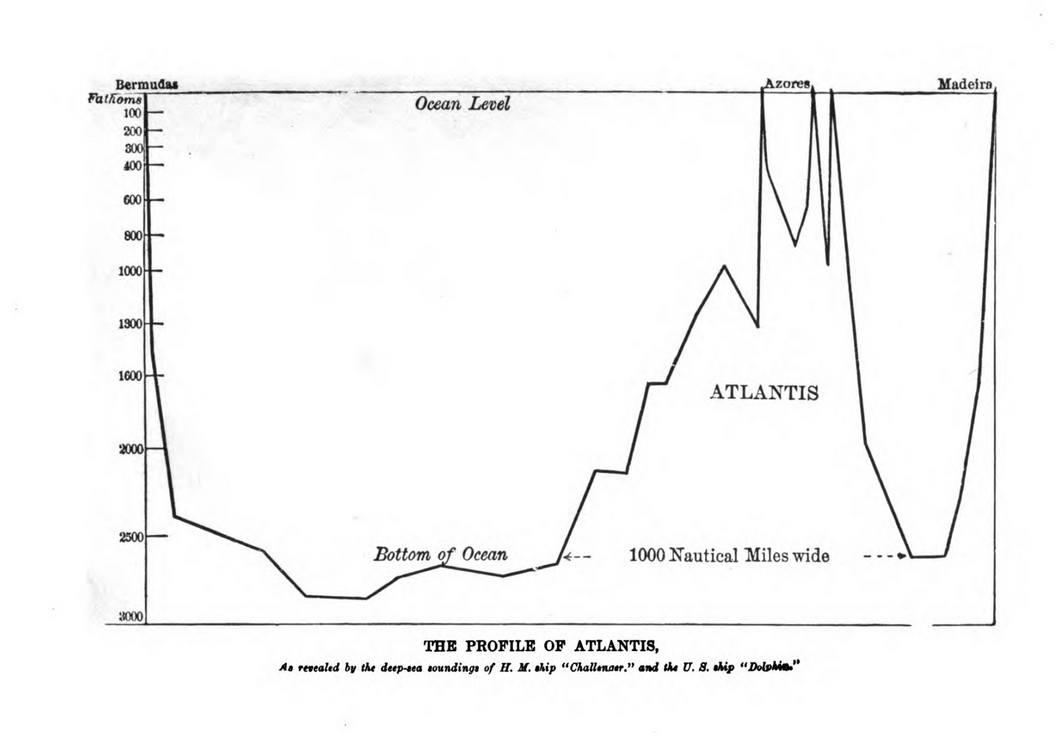

1. That there once existed in the Atlantic Ocean, opposite the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea, a large island, which was the remnant of an Atlantic continent, and known to the ancient world as Atlantis.

2. That the description of this island given by Plato is not, as has been long supposed, fable, but veritable history.

3. That Atlantis was the region where man first rose from a state of barbarism to civilization.

4. That it became, in the course of ages, a populous and mighty nation, from whose overflowings the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, the Mississippi River, the Amazon, the Pacific coast of South America, the Mediterranean, the west coast of Europe and Africa, the Baltic, the Black Sea, and the Caspian were populated by civilized nations.

5. That it was the true Antediluvian world; the Garden of Eden; the Gardens of the Hesperides; the Elysian Fields; the Gardens of Alcinous; the Mesomphalos; the Olympos; the Asgard of the traditions of the ancient nations; representing a universal memory of a great land, where early mankind dwelt for ages in peace and happiness…

What social and historical factors, I asked, could have made so many people want desperately to believe in the existence of Atlantis? My students knocked this out of the park. They instantly picked up on and unpacked the Biblical language of the text. They dissected terms like “barbarism” and “civilization.” Keen history majors recognized that the publication date put Donnelly’s book in the midst of an international economic depression and just after the assassination of two world leaders (Tsar Alexander II and President Garfield, both 1881), making the idealized vision of a peaceful utopia particularly attractive.

One student made the brilliant suggestion that Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species, published in 1859, gave rise to an interest both in human evolution and in scientific racism that later aligned with Donnelly’s insistence on Atlantis as the “original seat of the Aryan or Indo-European family of nations” (proposition #11). Indeed, students commented overall on how the myth of Atlantis could be appropriated for a range of political agendas, from Donnelly’s own populist rejection of corrupt Gilded Age politics to modern right-wing groups keen to locate the rise of true “civilization” in the ancient Mediterranean, rather than, say, Egypt.

But with popular television shows like the History Channel’s Ancient Aliens, not pulpy 1880s literature, serving as the primary vehicle today for myths about the ancient world, a lesson on pseudoarchaeology wouldn’t be complete without tackling the impact of television. So for part two of my plan we watched the first episode of Ancient Aliens’ shorter-lived cousin, In Search of Aliens: “The Hunt for Atlantis” (available in full on the History Channel website), starring Ancient Aliens mainstay (and meme generator) Giorgio Tsoukalos.

I’d been inspired by a colleague at a summer program for middle and high schoolers, who put on Ancient Aliens episodes on the last day of class to entertain his science students.[4] However, to retool a bit of term-end merriment for a practical, focused college lesson plan, I gave my students a worksheet to fill out with key concepts and questions as they watched the episode—incidentally, a good way to make students keep their attention on the screen—along with a self-created Pseudoscience Guide that listed and described various hallmarks of pseudoscience, e.g. misleading credentials, selective quotation, shifting the burden of proof and more. Identify at least three instances of pseudoscience throughout the episode, I told my students. Don’t just accept my word that this is bad faith archaeology—tell me why we shouldn’t put our faith in it.

From laughter at the melodramatic music cues to gasps of shock when pseudoscientist (and failed mystery theme park owner) Erich von Däniken insisted aliens impregnated ‘human females’ with part-extraterrestrial genetics, the episode kept my students’ full attention; Tsoukalos hunted for Atlantis, and fifty undergraduates hunted for clues of pseudoscience. Their worksheets, which I collected at the end of class, were remarkably detailed—one chemistry student took the time to explain to me the existence of a triple-stranded DNA model, taking exception to the episode’s clumsy grasp of DNA and fixation on the double helix.

Our Atlantis days were the most remarked-upon class activity in my end of quarter student evaluations. “I especially appreciated [them],” wrote one student, “because the material on pseudoscience will also be helpful for other fields we might encounter.”Crucially, my students’ conclusions about Atlantis and pseudoscience—whether from Donnelly or the in-class video—were conclusions they drew using their own critical analysis of text and media. Though I’m sure my personal opinions on pseudoscience were pretty clear, I didn’t force my students to muse, for example, on Atlantis’ appropriation by eugenicists or race scientists, or to notice Tsoukalos’ Indiana-Jones-like getup in In Search of Aliens. They got there on their own./p>

Blanket mockery of pseudoscientific myths with such broad popular appeal—and implicitly, of anyone who watches shows like Ancient Aliens, which might include students—is tempting, and nets laughs in the moment. Yet I am not convinced that a pedagogy of decontextualized disdain, with a flavor of the lofty academic speaking down to the ignorant masses, gets students comfortable engaging with the issues at hand. Nor do I think offhand mockery by itself really works to dismantle pseudoscience, any more than an adult’s snippy “it’s wrong because I said so” works on a child. Instead, giving students the tools to make up their own minds is the secret to success of teaching pseudoscience in the archaeology or classics classroom. You can lead a horse (or Atlantean elephant) to water, in other words, but you cannot make it think.

Header Image: Map of Atlantis by Athanasius Kircher, Mundus subterraneus, vol. 1. (Amsterdam 1678) (Image in the Public Domain via Wikimedia).

[1] Lisl Walsh, “What a Difference an ἤ Makes: Hippocrates, Racism, and the Translation of Greco-Roman Thought,” SCS Blog, November 1, 2018: https://classicalstudies.org/scs-blog/lisl-walsh/blog-what-difference-%… ; Sarah E. Bond, “Pseudoarchaeology and the Racism Behind Ancient Aliens,” Hyperallergic, November 13, 2018: https://hyperallergic.com/470795/pseudoarchaeology-and-the-racism-behind-ancient-aliens/.

[2] Winter 2018, UCLA (course instructor Prof. John Papadopoulos).

[3] Assigned for this class: Timaeus 21e-d, Critias 108e-121c.

[4] In the strong belief that pedagogical inspirations should be cited in kind with research ones, I want to acknowledge Dr. Rich Bykowski (Georgia State) for the glimpse into his summer paleobiology classroom at the Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth, and Dr. Lisa C. Young (University of Michigan) for her course on “Frauds and Fantastic Claims in Archaeology”, which made quite an impression on my own undergraduate years and helped me construct my pseudoscience guide.

Authors