Angela Holzmeister

June 27, 2019

Classics is a field immersed in the digital age. This isn’t news for anyone who teaches undergraduate language courses and has seen their students pull out their smartphones to access any number of dictionary apps that can find the first principle part of the verb εὕρηκα faster than you can find the epsilon-section in your Middle Liddell. But the field of Classics has done more than simply provide quick and easy applications to digital databases.

Digital humanists within the field of Classics utilize technology to produce a variety of digital projects that, among other aims, connect underrepresented scholars in the field, re-imagine the physicality of Classical sites, and redefine the space and model of scholarly contributions to the field. As of this week, several carbonized papyri scrolls from Herculaneum are on display at the Getty Villa, after being scanned using diagnostic radiological imaging and computer-mapping, allowing for these fragile scrolls to be digitally unfurled, read, and researched for the first time since the eruption of Vesuvius in 79AD.

In terms of interdisciplinary collaboration (those Herculaneum scrolls, by the way, were scanned at UCLA’s School of Dentistry) and breadth of application to the various and growing categories represented in digital humanities, Classics is leading her Arts and Humanities sisters, and always has, according to the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (TLG) Director Maria Pantelia, who reminds us that “Classics has always been at the forefront of technology. Remember, the TLG was established in 1972.”

When you recall that the World Wide Web went public in 1991, it is astonishing to consider that the TLG was conceived of in 1971 by UC-Irvine graduate student Marianne McDonald (later, professor of Classics and Theater at UC-San Diego). She imagined a databank of Greek texts to assist her dissertation research, and, a year later, provided the initial funding to launch what would become an internationally recognized research center and digital library resource.

In the early years, the TLG made monumental technological strides through the expertise of David W. Packard, then a Classics professor at UCLA, who developed the first encoding system for ancient Greek and invented the Ibycus system, which made the digitization of Greek texts possible. The first banks of digital texts were distributed via magnetic tapes and CD ROMs before the online site went live 2001 under the direction of Pantelia. Today, the TLG site holds all surviving ancient Greek texts dating from Homer to the fall of Byzantium, and its corpus pushes further into modern times.

The site receives over 300,000 hits a day. It also has over 600,000 registered institutional users (not including individual subscribers), and is visited by people from 73 countries. The TLG has become a reliable, if not necessary, academic resource for students and scholars, says Pantelia: “If I go by the messages I get every day, I would say that most scholars that work in different periods of Greek rely on the TLG to do their job… and when the TLG goes down for 30 seconds, we know it.”

Ever since the TLG made its texts available in its CD ROM days, it has faced issues of intellectual property theft (“ripping” of CDs, re-uploading without permissions, etc.), owing, in part, to a misunderstanding that the researchers at the TLG simply scan and upload texts. This couldn’t be further from the truth, as the process for uploading one text takes an entire team, hundreds of hours and many months. First, the team decides on an author and work, and identifies a text (from an edition or manuscript) that will serve as a “base document,” which is sent overseas to be digitized. When it comes back, the newly digitized “base document” undergoes scrutinous proof-reading. As Pantelia notes:

Once this is done, we begin the real work, which is the editing of the text. So, if there is a printed edition and we have the manuscript, we consult the manuscript. If there is more than one edition, we look at multiple editions. We look at the app crit. We always correct what we consider typos, but we may go beyond that. If we believe that a word is incorrect…we intervene, which we call ‘the TLG intervention’. So, once we go through that process, we also extract a list of words that are not attested anywhere in the corpus, and so we consider them suspect. We go through these words [to search for] typos or further problems in the text.

At this point, the text is uploaded into the server, where it undergoes further testing and indexing before it is eventually uploaded to the site for the public to see. “It’s a very long process,” Pantelia says, “Tedious. A lot of attention to detail, but we want to make sure the texts are accurate.”

Despite the critics of digital humanities like Stanley Fish, who asks whether “digital humanities offer[s] new and better ways to realize traditional humanities goals”, it is clear that the work Pantelia and her team produce at the TLG displays the rigor and humanistic aims of traditional Classical scholarship. The TLG doesn’t simply upload texts, rather the researchers at the center investigate and make discoveries and interpretations, which they then publish and share with colleagues in the field, similar to non-digital scholarly contributions. For example, Pantelia remembers that last year a user asked the TLG to upload a text of Metrodora, a female physician:

We discovered that there were two editions of the texts, one in Greek and one in Italian. We started looking at the Italian edition, and we saw that there were some problems there. And when we looked at the Greek edition, we realized that there isn’t much connection between the two of them, despite the fact that, to my knowledge, there is only one manuscript for this particular text.

In the end, Pantelia and her team sat down and reconstructed the text of Metrodora, using the two editions and the only known extant manuscript. The text uploaded to the TLG’s site represents an exciting intellectual endeavor and a painstakingly researched contribution to the field.

When asked how she might advise Classics graduate students in a market with declining teaching opportunities, growing institutional focus on digital humanities, and the reality, or necessity, of the “alt-ac” (short for alternative academic) market, Pantelia encourages graduate students to continue their traditional philological/Classics training, but also to be flexible in their career considerations. Pantelia herself began as student with a focus on Greek poetry and an interest in coding and technology, and now, as a faculty member in Classics at UC-Irvine, she has published on both Greek poetry and language and digital humanities, alongside her position as Director of the TLG, where she not only makes scholarly contributions with every upload, but also does much of the coding on the site and manages the website interface. With her own experience in mind, Pantelia advises students to take heart in the changing market, and to remember that their learned skills and talents in Classics are transferrable and may find expression in a variety of ways.

As for the future of the TLG? Pantelia believes in extending the concept of the TLG well into Late Antiquity and the Byzantine world:

[I subscribe to] the idea, the vision of Marianne McDonald who was the founder of the project, that the TLG should not just be Classical texts, but it should include Byzantine and modern [texts]...And that’s the direction we have taken. That’s where we’re going.

Additionally, Pantelia says that, with grant awards and other fundraising, the TLG endowment has grown under her direction so that soon subscription fees will no longer be required to support the project:

I am very confident…that before I leave the project, and hopefully long before that, the TLG will be free and open to everyone. So, everyone who has contributed financially, can think contributing to a TLG that exists in perpetuity.

Open access to these myriad texts is potentially the best news a Hellenist has read all day.

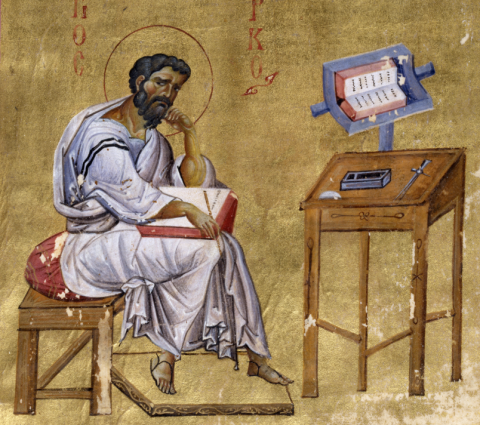

Header Image: "Evangelist Mark seated in his study," (11thC Byzantine manuscript, parchment, made in Constantinople and now at the Walter's Art Museum, W.530.A) [Image is in the Public Domain].

Authors