Christopher Trinacty, Emma Glen, and Emily Hudson

July 23, 2021

By Christopher Trinacty, Emma Glen, and Emily Hudson (Oberlin College)

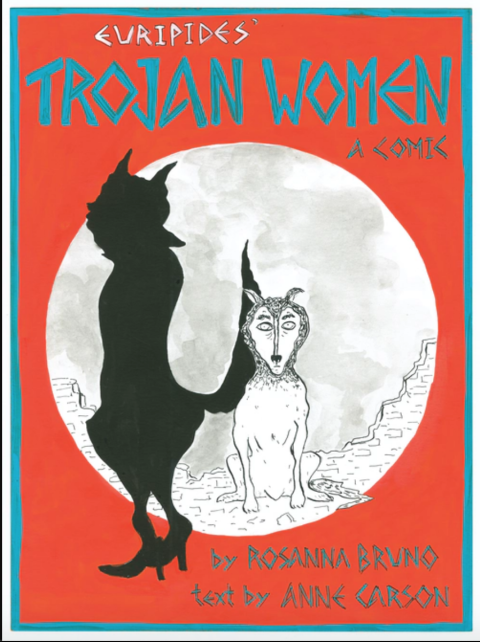

Anne Carson’s celebrated adaptations and translations of Ancient Greek and Latin literature have ranged from imagining the love affair between Geryon and Heracles in The Autobiography of Red to meditating about the death of her brother through Catullus 101 in Nox. In our opinion, Carson’s works highlight her theoretical sophistication as well as her deep commitment to the reception of Classics broadly understood. This new “comic” version of Euripides’ Trojan Women by Carson and illustrator Rosanna Bruno offers a creative and challenging take on Euripides’s tragedy.

Carson’s literary career has seen a consistent trajectory towards visual representation in the last decade. Nox incorporates various drawings and images alongside the text, and Antigonick, her translation and adaptation of Sophokles’s Antigone, is accompanied by several full-page illustrations by Bianca Stone throughout. Both pieces pair Classical texts with abstract, rather than directly literal, depictions of their contents, encouraging readers to consider the stories from different angles and create new meanings in the juxtaposition produced between word and image. Carson and Bruno’s collaborative Trojan Women expands the scope and scale of this practice by rendering Euripides’s play as a fully illustrated graphic novel. This Trojan Women feels more like a poetic and artistic exploration of the themes and motifs of Euripides’s play than a simple retelling of its plot through sequential art. Generally, it succeeds in conveying the pathos and existential horror of the tragedy and the experience of war from multiple perspectives.

The opening panel shows Poseidon as a massive tidal wave (à la Raymond Pettibon) and Troy represented by an old hotel “crouched on the plain like James Baldwin.” These verbal and visual fireworks indicate up front that this is not your average translation/adaptation of Euripides. Modern idioms, complex imagery, and allusions to poetry, painting, and film abound. The survivors of Troy are represented primarily as dogs and cows, with Helen pictured as a sable fox in high heels and the Greeks taking on various other forms. Hekabe is already a dog here, no metamorphosis to come, but the choice of making the animals enact the play (and the black-and-white drawing style) evokes Spiegelman’s Maus and works well.

Bruno, the author of a graphic novel about Emily Dickinson, has an aesthetic that can be stripped down or detailed, depending on the panels and the mood. Those who like the style of Alison Bechdel, Ben Katchor, or Lynda Berry will find much to enjoy in her art throughout the work, and the interactions between text and image help to hammer home the message of the drama. For instance, when Athene and Poseidon discuss destroying the Greek fleet, we find grim imagery and stark prose: “Poor clowns! They need a lesson! Why? Because they broke something of ours. Because they squeak when they die. Because we can” (p. 13). In this spread, Greek ships are split open like ripe fruit, with the men mere pulp to be dispersed in the sea.

Hekabe (“an ancient emaciated sled dog of filth and wrath”) offers an evocative opening speech: “What are words for? Have I ever been as bad as this? No, I have never been as bad as this…what are cries for? Can we strangle the muse?” (p. 14). Carson and Bruno choose to keep the chorus, now of cows and dogs, and introduce them like a police line-up of mug shots. The first ode is rendered rather accurately on the left-hand page and then a sort of negative image on the right hand side takes liberties and updates the words to evoke enslavement in the United States (“Say, Mr. White slaver”) or current-day sex trafficking (“Will the work involve sex?...Can I call my parents?”). We found this to be very effective, with such updated dialogue hitting home like a punch to the gut and reflective of the reality of modern war crimes and refugee stories.

.png)

Figure 1: The Chorus. © 2021 New Directions Books.

Kassandra enters next, brandishing torches nearly as large as herself. Notably, she is the only character depicted as a human, except for a single illustration of Paris later on. Kassandra’s human form is significant; it is indicative of her ability to register a different, perhaps more accurate, reality. While the other characters in their animal forms stumble through the play’s events somewhat blindly, always wondering what will come next for them, Kassandra clearly perceives her own fate and that of others around her. She explicitly states that through her marriage, she will “kill Agamemnon and desolate his house” (p. 24). Her human form intimates her prophetic abilities; she reiterates her paradoxical idea that “Troy won the war” (pp. 24–26), inasmuch as the Trojans have graves, funeral rites, and families to mourn them — or at least they did so — and they have won everlasting fame.

Not all of the physical forms chosen for the characters land quite as well as Hekabe’s or Kassandra’s. Andromache and Astyanax, for example, are represented as a poplar tree and a sapling, respectively. Although Polydorus is referred to as a “sapling” (πτόρθος) in Euripides’ Hecuba and Astyanax is called stirps, “seedling,” in Seneca’s Troades (and we appreciate the “family tree” metaphor), this representation results in an almost comical tone being applied to what is arguably the most tragic moment in the play, as Astyanax is ripped from Andromache’s arms. While the black-and-white coloring highlights the disparity in her fortunes — mirrored with the language “It’s the contrast stuns me. Yesterday we were royal persons living unexamined lives. Now what?” (p. 38) — there is little sense of the human emotion that is present in the original. Rather, the tears dripping from non-existent eyes on a non-existent face sterilize the scene and cause the tragedy of the act to fall flat. Andromache suffers from this same effect. As the character in the play who possibly suffers the most, the audience would expect her to take on a form that exhibits the pain she is experiencing. Yet representing her as a tree limits the human, or even animalistic, expressions of grief and trauma that she makes throughout her time on stage.

.png)

Figure 2: Andromache and Astyanax. © 2021 New Directions Books.

The catalogue of figures used to represent Euripides’s characters grows increasingly more surreal throughout the play, moving from the realm of animals into that of objects. Menelaos appears as a floating, round mass of mechanical wheels, “some sort of gearbox, clutch or coupling mechanism, once sleek, not this year’s model” (p. 52). The meaning of this imagery is left to the reader to interpret: does it represent his inhumanity as the callous arbiter of so many women’s lives and deaths, or perhaps the idea that he is more a “cog in the machine” of war than an active player? Helen, too, bears mentioning here: the audience sees her drawn as a fox, until she is revealed to have “a changeable form, sometimes a silver fox, sometimes a large hand mirror” when she makes her first official entrance. This duality stresses the subjectivity of various characters and draws attention to the audience’s views of Helen’s role in this disaster. Is she an agent of her own desires, as Hekabe would have it, or an object “bought and sold,” as she herself claims (p.57)? Bruno and Carson’s artistic decisions are as thought-provoking as the text they illustrate. The transformed characters metapoetically mirror the author and illustrator’s transformation of the play.

The work ends on a strong note, as smoke envelopes the final pages; the characters are shrouded and gradually disappear in fire and fumes. The final words echo Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable, as Hecuba says, “We can’t go on. We go on,” taken up by the Chorus claiming, on the final page, “we go on.” This concluding page, a black background with a white spotlight circle on one of the Greek boats heading home, feels cinematic. One wonders about the sequel. Is this Odysseus’s ship? Is Hekabe on it? Should we think of her future transformation into a canine-shaped landmark (Kynosema) on the Chersonesus, or the future destruction of a majority of the Greeks? Regardless, this graphic novel will stick with you after you finish it and will be appreciated by scholars and students of Greek tragedy.

Authors