John Franklin

December 21, 2020

In memoriam Stellae Q. Decimae

Lucerna ardens extinguitur

In March 2019 the Classics Department of the Universitas Viridis Montis posted a piece on the SCS blog about the ongoing austerity measures afflicting our old program, despite enrollment numbers that have been comparatively healthy for the field (including 31% growth in majors since 2015) and a long record of public outreach befitting our Land Grant mission. By now many will have heard that Dean William Falls has proposed to abolish permanently UVM’s majors and minors in Greek, Latin, and even Classical Civilization, as well as our small but vivid MA program. Other departments slated for demolition are Religion and Geology, along with eight other majors (German and Italian among them), eleven minors, and three further MA programs. Falls is acting under semi-reluctant but well-compensated compulsion from an 8.6 million dollar “structural budget deficit” that has resulted from the controversial Incentive-Based Budgeting system that former Provost David Rosowsky implemented in 2015, which led eventually to a no-confidence resolution by the College of Arts and Sciences faculty. Despite initial promises, the new Administration—in-house Provost Patricia Prelock and President Suresh Garimella, ex-Purdue and Trump appointee to the National Science Board—shows no will to address the inequity from on high, but prefers to guide discreetly this putative but actually rigged free market of tuition dollars and student credit hours, lopsided ‘multipliers’ that drain away Arts and Sciences ‘revenue’, crushing ‘head-taxes’ that prevent benefitting from local diversity of expertise, under-accountable ‘cost centers’—recently rebranded as cozier ‘support centers’—and predatory competition between the university’s colleges. In a brilliant analysis the late, lamented biologist Charles Goodnight explained how IBB produces “a plot of ‘mean’ plants that fight for resources rather than cooperating to raise overall yield”.

These are carcinogenic, catastrophic changes for a flagship state university that for generations has provided vital opportunities for Viridimontani and Campestres alike—in this case training and supporting a network of high school Latin teachers in and beyond the Green Mountains; offering a promising path to PhD programs for a very diverse battalion of aspiring professional scholars; and steadily promoting the passionate minority of quirky misfits that share a fascination with the ancient world, whatever their eventual occupation.

Details of the Administration’s proposal, and the cross-campus activism it has ignited, can be found in a growing array of pieces online (including Forbes and Inside Higher Ed) and on social media (the United Academics Facebook page is a useful portal). Jeffrey Henderson and Sheila Murnaghan have provided a stern letter from the Society for Classical Studies that, among other things, calls out the Administration for focusing on number of majors rather than overall student credit hours taught—the more honest measure of a department’s intertentaculation with the larger campus organism (thus 700–900 students taught in a year can be reduced to a mere handful). Sean Gurd has nobly spearheaded a protest by classics PhD-granting chairs. UVM is also front and center in the ACLS’s “Important Reminder of the Urgency to Uphold the Central Role of Humanistic Study In Higher Education.” Further epistolary support is arriving from other professional organizations, extramural colleagues, Vermont high school Latin teachers, and outraged alumns. A change.org petition started by Meghan Keefe, president of the venerable Goodrich Classical Club, has gathered more than 4,800 signatures and numerous impassioned testimonies about the far-reaching impact the department has had on individual students and the larger community over many decades (please sign!). Penny Evans, on the department faculty, published a moving open letter about her escape from rural Vermont poverty via high school Latin with UVM alumna Karen Knapp, a BA/MA from UVM, a PhD from Trinity College Dublin, and finally a welcome nostos to help renew the home tradition. Selected tributes are being broadcast on the department’s Facebook page.

Stay tuned for more of this sad, sordid story—a caution to all—which will want the rest of the academic year to unfold, and possibly the fall. The Department is still recruiting what will probably be a Last Waltz cohort for the MA program (a teach-out window must be provided for declared Greek and Latin majors), so get those applications in and join the band! (Lyres and pipes will be provided.)

Meanwhile, let the case be put before field and broader public that, if UVM’s Administration does indeed ram through the intended cuts—as now seems likely, with or without faculty confidence—the university should surrender its motto, Studiis et rebus honestis. This would be only right for the sake of truth both in advertising and to the historical record.

Horace’s words, from Epist. 1.2, were officially adopted by 1804, in time for the first formal graduating class (after foundation in 1791). It should therefore be considered the University’s original statement of purpose. The phrase is indeed still much buffeted about in official messaging, though the original context—essential for understanding the motto’s true intent—is long forgotten by most faculty and all administrators.

.png)

The Roman poet composed his letter-in-verse shortly before 20 BCE for a young friend immersed in the study of law and rhetoric at Rome, a normal preliminary to an honorable course in public affairs. He urged Lollius to balance his professional exertions with the equally ‘honest’ study of classical literature, to learn vital lessons about life and leadership that would be counsel and comfort for all his days.

Horace elaborates only two examples of these ‘studies’. The Iliad and the Odyssey, he held, were more valuable than even the philosophers. The great war poem teaches us how not to live, to ward off destructive passions ruinous for individual and society—sedition, deception, fraud, rage, unbridled lust, failings of foolish autocrats (stultorum regum) that destroy those under them. The homecoming epic—the Homeric text that UVM’s sophomores read before Horace himself—shows “what courage and wisdom can do”, and exhorts us not to emulate the suitors, lolling abed until noon and lulling our cares to the crepitous lyre. Sleepless nights of torment, Horace warns, await us unless we rise before daybreak, light a lamp, and exercise ourselves, heart and soul, in studiis et rebus honestis.

That UVM’s founders had Horace’s exact message in mind is shown by the official seal, in place by 1807 and thus closely synchronized with the motto’s adoption. Behind the original college building one sees the sun rising over the Green Mountains, as though we have just finished the fundamental business of working through an episode of Homer, fortified for a day of more mundane, ‘practical’ pastimes.

.png)

The oldest surviving UVM curriculum, 1835 (Image provided by the author).

A first-year student spent Autumn mornings on algebra, with classical literature in the afternoon. In Summer Term (March–July) the order was reversed—a fibrous course of classics first, geometry for dessert. Such mirroring was maintained in the second year, with the pattern reversed. These striking symmetries emphasized the vital complementarity of what we would now call Humanities and STEM. There is much more to say about the development of UVM’s early curriculum, for which one may consult the essential study by Professor Emeritus Z. Philip Ambrose. Here are his comments on Studiis et rebus honestis:

The appeal of [Horace’s] poem to the framers of the UVM motto is obvious. Admonitions to rise and shine, to burn the midnight oil over a book, to practice frugality and avoid envy, and especially to nurture the mind and character read like articles in the UVM Laws . . . “Dedication to studies and honorable pursuits” . . . and “Integrity in Theoretical and Practical Pursuits” . . . are attempts at turning the phrase into a motto. But in the very first years of the University, “studies and honorable pursuits” meant “literature”, not only the Greek and Latin classics but any literature whose “rereading” was useful (in effect, Horace’s definition of a classic at the beginning of the poem). (Ambrose, Z. P., “The Curriculum—I: From Traditional to Modern”, in Daniels, R. V. (ed.), The University of Vermont: The First Two Hundred Years 1991), 89–106, here 93–94.)

Professor Ambrose further reflected, in a recent exchange, that

When the [Agricultural] College first arrived [in 1865], its students basically followed the traditional curriculum, but gradually the uniformity of the UVM curriculum began to crumble. So what does studiis et rebus honestis mean after that? With some pride the framers of “Theoretical and Practical Pursuits” looked back to the early curriculum, innovative for its time; but if I’m sure of anything, Horace would have been completely baffled by this interpretation. (email, January 15, 2020, emphasis added).

Times change, and we ourselves change with them. Yet through UVM’s many changes—dropping the Greek and Latin requirement for the BA in 1941, the two years of Latin for an English BA in the 1960s, the disastrous lowering of the language requirement to just one year a decade ago—a Classics curriculum, complete with Greek and Latin, was maintained and valued not only for preserving UVM’s historical core, but as having much yet to contribute to the common good. The Department has always done its best to give back to College, University, and above all to the Fourteenth Star itself and New England more broadly—from forty-five years of Vermont Latin Day that brings to campus hundreds of high school students, to working with military veterans, prison populations, and most recently productions of ancient drama in collaboration with community artists and local schools (Euripides Helen, 2018; Aristophanes Clouds, 2020). We have also taught many Greek and especially Latin majors from Maine, Connecticut and Rhode Island via the New England Board of Higher Education Tuition Break program—willfully neglected by UVM, despite Garimella being an ex-officio board member.

The value of such a program cannot be calculated by its number of majors. Even an honorable acknowledgement of overall credit-hours-taught would fall far short of capturing how the picture develops over many years beyond campus. As Richard Thomas has written,

The value of Classics at the University, and throughout the state of Vermont, is one that can only be assessed through the accumulation of personal stories of improvement and social advancement that have come through the benefit of a robust liberal arts education.

One might argue—as UVM’s Administration does—that losing Greek and Latin as formal programs of study will not prevent students from reading the Classics in translation and so receiving the same benefits as ever. Such courses are indeed a vital service at a public university, and the Department has taught them gladly for many decades; these classes made our student-to-faculty ratio higher than that of any other humanities program, prior to two unreplaced retirements and an opportunistic Senior Lecturer termination. Yet such a curriculum must be firmly grounded in the discipline. (Imagine studying Shakespeare in Russian, Arabic, or Chinese from an instructor lacking any English.)

The truth of this assertion was recently reaffirmed by my veterans-only course, Home from War: The Odyssey, which welcomed back, into UVM’s inner curricular sanctum, soldiers who had seen many cities and minds. The class made international headlines, and was pounced upon for promotional purposes by the Administration, despite having been taught as an uncompensated overload because of already scarce teaching reserves. Discussions were as challenging as those encountered in the advanced seminars now slated for demolition. Practically limitless interpretive issues arise in any two books of Homer, and for each session careful preparation with commentaries and secondary literature was required for being well armed against narratology and cultural context.

This need for proper disciplinary training is why, contrary to the all-too-common administrative view that humanistic inquiry is little better than astrology—the academic equivalent of F*** your Feelings—Classics is not a salted field. Ancient texts are not fixed, but continually revised. They have as much to teach us as ever—more so, indeed, as we seek to advance greater diversity and self-knowledge (as Penny Evans eloquently elaborates in her open letter to UVM). And for this, public universities are a crucial point of access.

In UVM’s attempt to stop supporting Greek, Latin, and other targeted programs, we see its “comprehensive commitment to a liberal arts education”, as called for in the University’s official mission statement, slipping into a mere “exposure to the humanities”—the ominous and grotesque expression that Garimella smuggled into his personal vision (“Amplifying our Impact”). In other words, if UVM sparks an interest, you can pursue it more some day. After college. On your own. The Neoliberal Arts—where students learn not ‘how to’, but only ‘about’. We will be unable to maintain our long community outreach, or hand forward a more than 220-year tradition of Studiis et rebus honestis by recruiting well-qualified replacements upon retirement—which looks hardly likely in any case, as things now stand.

I therefore call upon UVM to surrender its motto. This is one revision of an ancient text that should not be suffered.

Casting about for a suitable substitute, Stultitiis et rebus infestis recommends itself as both well reflecting the current state of affairs, and enjoying a kind of parallel authority in Horace’s sermon. Some kindly ghost in Google Translate, to which UVM’s Administration may care to resort (or not), offers the curiously lyrical and suggestive “Folly: but the things in dangerous times . . .”

“A Foolish, Slimy Business” would be more accurate.

If some more positive slogan be sought, and Latin still have some cachet to cash in, the Classics Department is here and happy to help—as we always have been—for a little while yet.

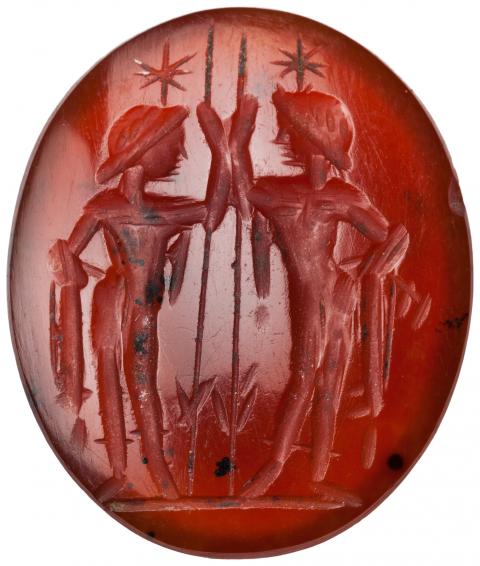

Header Image: Carnelian seal of the Dioscuri standing facing, heads to center, each with star over head and holding inverted spears (Image via the American Numismatic Society, CC BY-NC 4.0).

Authors