Nina Papathanasopoulou

July 10, 2019

The new Classics Everywhere initiative, launched by the SCS in 2019, supports projects that seek to engage communities all over the US and Canada with the worlds of Greek and Roman antiquity in new and meaningful ways. As part of this initiative the SCS has been funding a variety of projects ranging from children’s programs to teaching Latin in a prison. In this post we focus on two programs that bring the study of Greek and Roman antiquity to two traditionally underserved communities: incarcerated students in a correctional facility and the racially, ethnically, and economically diverse community in Winnipeg, Canada.

There is a pressing need to make Classics more open and inclusive, and to diversify the voices dominating the study of Greek and Roman antiquity. A growing number of classicists are rethinking the field's often unspoken assumptions, exploring the ways in which contemporary scholarship may be affirming or challenging existing social structures, and reaching out to more diverse audiences, to encourage new responses and perspectives.

In an attempt to connect the diverse population of Winnipeg with the study of antiquity, Peter J. Miller, Assistant Professor of Classics at the University of Winnipeg, has been organizing a lecture series that brings Classics into dialogue with other fields. At the same time, the series focuses on issues local to the Winnipeg community, as well as the current state of events in Canada and the US. While describing his goals for this series Miller explained:

We aim to show the longevity, vitality, and novelty of Classical scholarship, to connect with people inside and outside of the university, and to encourage students, faculty, and members of the public to recognize the important role Classics plays in Winnipeg's social, cultural, and intellectual life, and its role in Canada and around the world.

Scholars included in the series have presented on Native-American engagement with Greco-Roman antiquity and Korean, Chinese, and Japanese reimaginings of Greek tragedies such as the 1994 Contemporary Legend Theatre’s Beijing Opera production of the Oresteia, and Ong Keng Sen’s 2013 Trojan Women with the National Changgeuk Company of Korea.They have also collaborated with local craft brewer Barn Hammer Brewing in order to recreate a recipe for an ancient beer. Their work has also reach out to other departments within the university: with the Department of Economics to present on ancient economies and with the Faculty of Kinesiology and Applied Health for a presentation on the modern Olympics.

This coming year, Miller is partnering with the Department of Urban and Inner-City Studies to organize two talks at the University of Winnipeg's new Merchant’s Corner campus in Winnipeg's "North End." First, Matthew Sears, Associate Professor of Classics at the University of New Brunswick, will give a talk entitled “Presence and Absence in War Memorials, Ancient and Modern” on October 25. On March 20, Rebecca Kennedy, Associate Professor of Classics at Denison University, will be presenting on the ancient and modern discourse on immigrants and refugees by examining in combination tombstones and Attic tragedy. According to Miller

Winnipeg's "North End" is one of the poorest communities in Canada, and one in which racialized poverty is most evident. Indeed, in Winnipeg-Centre (where the University is located) and Winnipeg-North (where the Merchant’s Corner Campus is located), 41.1% and 32.3% of children live in poverty, a far cry from the still shocking Canadian average of 19.6%. The population of the North End and downtown is one of the most racially and ethnically diverse in Canada, with nearly one-quarter of residents identifying as First Nations, Métis, or Inuit, and another quarter identifying as an ethnic or racial minority.”

The SCS’s Classics Everywhere Initiative is funding these talks, both of which will focus on the issues of appropriations of Classics in contemporary politics, Classics and white supremacy, and Classics and indigeneity. By holding the talks at this location, Miller hopes to build connections between the University – its faculty, staff, and students – and the North End, where Classics has not had a robust presence previously. The talks are conceived in part as a response to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which called on Canadians and Canadian institutions to work towards reconciliation and decolonization; and to the University of Winnipeg’s own strategic directions, which include indigenization and public knowledge mobilization. The public lectures participate in the task of reconciliation by aiming to engage more deeply with Canada’s Indigenous people, their history and lived experience, and the role of Classics in perpetuating racist structures – especially in Winnipeg which is home to the largest population of Indigenous peoples among Canadian cities.

Figure 1: Peter J. Miller introducing his lecture series

“New Directions in Classics” at the University of Winnipeg

(Image Credit: University of Winnipeg).

As many of the projects included in the Classics Everywhere Initiative exemplify, Classics isn’t solely located in university lecture halls. Hoping to foster excitement about Classics in marginalized communities, Nebojsa Todorovic, a 3rd year PhD student in the Comparative Literature program at Yale University, recently taught an intensive elementary Latin course to nine male incarcerated students at McDougall-Walker Correctional Institute. Todorovic was born in Sarajevo, grew up in Italy, and works on the reception of Greek tragedy in the Balkans during the Yugoslav War. Todorovic’s five-week intensive Latin course was part of the Yale Prison Education Initiative at Dwight Hall (YPEI) and was funded by the Classics Everywhere Initiative, the Classical Association of New England, and the Classical Association of Connecticut. As Todorovic notes, there is a perception of Classics that must be addressed and changed:

Learning Classical languages is often associated with class privilege, with an aura of detachment from the contemporary world. The motivation and the excellent results that my incarcerated students have achieved shows that Latin, when made accessible to traditionally underserved populations, can offer a window into a new and formerly unimaginable world. Learning Latin, my students became interested in questions of language and linguistics, law, science, social history, literary history, and more. In a sense, they "resuscitated" a language that is far from being dead.

Todorovic taught for three hours each morning for five days per week. After class, volunteers worked with the students in small sessions to help them solidify what they were learning.

For me, teaching Latin in prison has been a revelatory experience. The intense pace combined with my extraordinary group of students (the most motivated and engaged students I have ever taught), always kept me on my toes. The students were bright and eager to learn, profoundly demonstrating the intellectual and academic might our society has left to languish behind bars.

The students were delighted to have learned Latin too. One student noted:

Latin is like Mathematics. I’ve learned that you cannot guess at an answer. Latin forces me to think inside of the box and to follow rules similar to close reading strategies. I continue to use the skills I have developed in Latin outside the classroom.

Another reported:

Learning Latin has helped me develop analytical skills. Nebo took the time in showing us how to break down a single word all the way to translating entire Latin passages. This program also taught me patience in learning and an understanding that it's a process and if I stick to it I can succeed.

The Founder and Director of the YPEI, S. Zelda Roland, is eager to report on the breadth and progress of the initiative:

Last summer YPEI was able to offer our first Yale courses to incarcerated students in CT state prisons, marking the first time any incarcerated students anywhere have ever earned real Yale credits, which appear on real Yale transcripts. We are extending access to what is perceived to be one of the most elite credentials in American higher education to a group of students who have been among the most systematically deprived of access to higher ed.

Roland decided to include Latin as a course this year because “it really demonstrates our commitment to the liberal arts. The liberal arts teach you how to think critically, and they are not widely available in prisons.” According to Roland, their program “extends access to the type of education that we believe the best and brightest minds in this country should have, to the best and the brightest who happen to be on the wrong side of mass incarceration.”

While teaching in a prison is rewarding, it also comes with challenges. Everyone must abide with the rhythm of the prison facility, which can be limiting. Students can never be left alone and an officer has to oversee all students at all times. Instructors cannot be late, as the facility allows entry only at certain times, and they must undergo a daily security check. In addition, the facility has no internet, so instructors and students cannot correspond between sessions.

Todorovic’s experience shares much with the experiences reported from a variety of scholars teaching in prisons during a panel devoted to “Classics and the Incarcerated: Methods of Engagement” at the 2019 annual meeting in San Diego. For those interested in participating in such an experience, the Classics and Social Justice group has gathered information on teaching in prisons on their website.

The work of Miller,Todorovic, and Roland are just a few examples of the valuable work being done by individuals to make the study of the ancient world accessible to traditionally marginalized and underserved groups. The Classics Everywhere Initiative is looking to sponsor projects for 2020 and will welcome new applications in October, February, and May. More information can be found here.

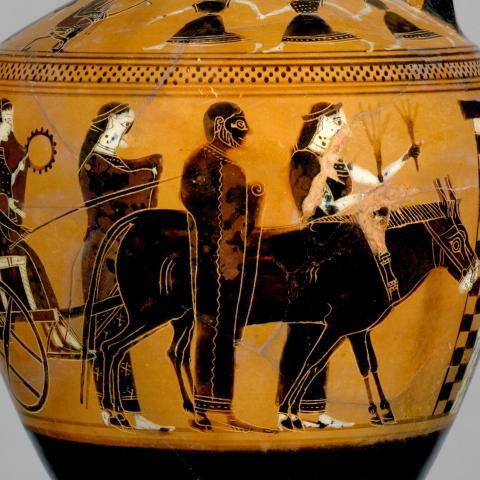

Header image: Terracotta lekythos (oil flask),ca. 550–530 B.C. Attributed to the Amasis Painter. Image via Metropolitan Museum, CC0 1.0.

Authors