Piper Hays

September 26, 2023

Content forecast: sexual assault

There’s a saying on my side of the internet that goes: “Don’t kill the part of you that’s cringe. Kill the part that cringes.” I’m a fervent supporter of liking what you like, as long as it does no harm. So, for a long time, I’ve really tried my best to understand one of the newest literary trends to hit the fiction market.

Yes, you read that title right. Gone are the days of cartoonishly evil portrayals with their flaming hair and murder plots. I am a bit embarrassed to announce that Hades, Greek God of the Underworld, is the newest hot guy to hit the teenage psyche.

It’s not exactly a new trope. Dark, torn-up, melancholy men have been a fixture of fiction for centuries, from Hamlet to Heathcliff to Edward Cullen. But Classicists might be confused, or maybe even a little appalled, to see Hades posed as the newest brooding, sharp-jawed object of teenage affection. After all, we know what the ancient texts say: Hades kidnaps Persephone, confining her to the Underworld and, in some versions, tricking her into eating pomegranate seeds to keep her there for half the year. It’s been a story of rape and captivity for thousands of years. So why has the collective tune changed?

To discuss this sudden cultural phenomenon, I’ll be looking at translations of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which has one of the more widely known versions of the Hades/Persephone myth. Traditionally, translations of Ovid have glossed over occurrences of sexual violence against women in favor of beautifying the prose. However, recent translations have shown that softened terminology exists in more than just the Metamorphoses: it’s an endemic problem with older translations. Stephanie McCarter recently published a translation of the Metamorphoses around which she discusses the glamorization of sexual violence. In older translations, McCarter notes, Ovid’s women are “defeated,” “ravished,” “won over,” or “ardently wooed,” rather than raped or violated.

In contrast, McCarter’s translation makes an effort to name the action as faithfully and starkly as possible. Of course, there’s no way of knowing exactly what Ovid wanted us to glean from his poem (unless we discover necromancy). The terms describing assault rely partly on cultural context to be fully understood, but are often translated with romantic language that obscures these negative connotations, leading to confusion about the action’s severity and lack of consent.

Kids These Days: Reception of Classics in the YA/NA demographic

Thanks to a renewed interest in Classics in contemporary media, more students are being introduced to works like Ovid’s through translation at younger ages. I first read Ovid in Grade 9, back in 2018 (yes, I was fourteen in 2018. Feel old?). My school library didn’t have any newer translations, so I found the link to the Perseus Project. It was free and, as a high schooler, that’s all I really needed.

At the time, I didn’t know what words like “ravished” meant in their historical context. All my little nerd brain knew was that “ravishing” meant beautiful, and the translation included professions of love. So I assumed Persephone had at least some say in her relationship with Hades, and that consensual romance was involved. But that was in high school: what about college?

Unfortunately, even postsecondary students aren’t always safe from the dangers of romanticized translation. In interviews, McCarter brings up a 2015 op-ed by students at Columbia University that called for trigger warnings on Ovid and other texts containing sexual violence. In the article, the authors expressed concern that their professors chose to focus not on the occurrences of sexual violence, but the beauty of prose and imagery that describes it. But when students voiced these concerns about how the Metamorphoses was being taught, it was the article that launched a thousand think pieces about the death of free speech, undermining the arts, and the funniest term I’ve ever seen used seriously in an article: “totalitarian gobbledygook.”

A lot of these retributive op-eds misunderstand the intent of the article on their path to blowing it out of proportion. The Columbia students weren’t asking to purge Ovid from the syllabus. They explicitly stated that “our vision for this training is not to infringe upon the instructors' academic freedom in teaching the material.” What they’re asking is that the Metamorphoses be treated as what it is: a poem which documents over fifty occurrences of sexual violence. The romanticization of rape can be as difficult to escape as an undergrad as it is confusing when you’re a teenager: it’s problematic to expect the necessary media literacy from kids when the establishment won’t even acknowledge the problem to adults.

Many younger students are more likely to absorb Classical literature via fiction that is largely written by authors without much Classical training (if any). At the same time, many of these authors are working from the same euphemistic translations. By the time the stories arrive in the hands of the youth, they’ve created a false but widely accepted narrative that’s hard to combat.

Okay, But What Even Is a BookTok?

In times like these, many teenagers seek the catharsis of an ideal life in literature, and trends in media tell them that nothing is more ideal than a mature, attractive, unattainable love interest who treats only you like a queen. This brings me back to the conundrum of the Hades and Persephone that many teenagers are coming to know via young adult (13–17) and new adult (17–21) fiction.

Classical reception in teen-oriented literature has seen an upswing in popularity on social media apps like Tiktok, with subcommunities dedicated to reading and reacting to those stories (that’s what a BookTok is, by the way). In this case, Hades fits the bill better than other Greek mythological figures: he’s well-known enough to have relevant source material, but darker and more mysterious than Apollo, less prone to adultery than Zeus or Poseidon, and he has a wife who’s translated as young and powerful, to whom he is devoted (regardless of whether she wants it). No wonder authors think teens will flock in droves towards that sort of dynamic.

In accordance with this trend, “Hades and Persephone” is not cast as a story of an older male kidnapping, raping, and forcing a much younger girl into marriage against her will. Instead, it’s a hot-and-heavy, enemies-to-lovers dark romance where Hades is a handsome, protective (read: possessive), morally grey billionaire/king/crimelord/whatever who is utterly devoted to and ready to burn down the world for his preternaturally beautiful, spirited, and barely-legal Persephone.

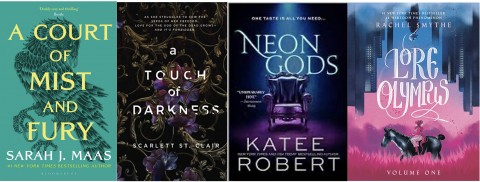

This characterization rings true of many adaptations, whether or not Hades’ and Persephone’s names are actually ascribed to their characters. Rachel Smythe’s webcomic Lore Olympus, which garnered over 5 million readers by 2019, centers around sheltered, young Persephone as she falls in love with Underworld business magnate Hades. In the bestselling A Touch Of Darkness series by Scarlett St. Clair, Hades is again a wealthy businessman who gets together with virginal young journalist Persephone.

Rachel Smythe does cite the Metamorphoses alongside the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, the Iliad, and the Odyssey in her research for Lore Olympus. But rather than referring to the details of the myths themselves, these adaptations tend to draw on the ambiguous relationship exhibited in translations. What’s more, these pieces attempt to excuse the “romance” with a modern setting and customs — gods are socialites or billionaires rather than kings. They fall short, however, by emulating elements of Ancient Greek myths and customs that we would find abhorrent (i.e., abduction of women, and old men marrying really young girls) but are romanticized in translation.

This isn’t to say rape is erased entirely. Lore Olympus does deal with sexual violence — just not between Hades and Persephone. Instead, Persephone is raped by the story’s Apollo, who is cast as a serial assaulter (which might be the closest the story gets to characterizations borne out in the source material). However, Hades is written as a caring and protective partner, supporting Persephone as she learns to speak out in defense of herself. Never mind that, in Ovid’s version of the myth, he was the rapist, not the consoler.

The characterization of Smythe’s Hades seems to stem from the same broad misconception to which other retellings fall victim: an understanding of the myth derived from translations that highlight Hades’ affection towards Persephone while obscuring the abduction itself. That’s part of why it’s important to translate similar occurrences of abduction and assault with consistent contextual phrasing. Apollo’s myths are more prevalent in the Metamorphoses, and so it’s easier to connect the dots between his many accounts of sexual violence despite the varying glamorizations of the act. Hades, who appears in the Metamorphoses very rarely, has less of a chance to be translated using appropriate terminology when translators are so insistent on avoiding “ugly” words like rape as much as possible.

In other adaptations, like Scarlett St. Clair’s novels, Hades is threatening and possessive over Persephone’s virginity, but he never actually violates her sexually (her attraction to this possessiveness is another can of worms entirely). His characterization crisscrosses between the abductor of ancient myth and the morally grey “I would burn down the world for you” men that teenage girls like to swoon over. Eventually, the two concepts become so intertwined they’re almost inseparable. All the pre-existing problematic aspects of Hades as a mythological character are features where once they were flaws. When Hades and Persephone are brought up nowadays, it’s to say things like “I tend to ignore the fact that Hades kidnapped her and their story had a rocky start,” because their relationship has become synonymous with romance rather than rape. But it’s fine, kidnapping is okay as long as it’s monogamous!

“Gross,” you might say. And also, “That’s a departure from the myth, but how is it my problem?” (And maybe a healthy dose of “For reasons completely unrelated to this, I am going to check my kid’s bookshelf for these titles.”) And you’d probably have a point. But if you compare this media with easily accessible translations, you might not find that much of a disconnect. The portrayals of Hades and Persephone in media are unhealthy, as many relationships in young and new adult media are. But at their core, they’re just romantic versions of already romanticized translations. Rather than being contradictory, translations and adaptations reinforce each other in an almost ouroboric cycle, creating a pervasive narrative of romance rather than violence.

For all the damage that Hades and Persephone narratives have done to the teenage perceptions of romance and myth, their flawed adaptation might also be their saving grace. Easily accessible translations of the sexual violence in the source material become essential when it comes to depicting the reality of these toxic relationships. By problematizing this relationship dynamic in translations and adaptations, we can discourage young readers from romanticizing aspects of it, or from emulating and pursuing dangerous traits they might otherwise find attractive. Rather than protective, brooding, and mature, they can see controlling, petulant, and waaaaay too old.

Listen, I don’t want to rain on anyone’s parade. At the end of the day, all these adaptations are fiction, and authors can choose to take creative liberties wherever they please. My concern is when checking on those inaccuracies isn’t as cut and dry as just reading the source material. It shouldn’t take years of schooling to be able to recognize the dark nature of these ancient poems, and controversial op-eds shouldn’t have to be written in argument of teaching them fairly. If we translate and teach these ancient works as stories of rape from the get-go, we might be able to avoid any further romanticization of rape and kidnapping (which I think we can all agree is a good thing).

Authors