Christopher Parmenter

March 3, 2022

When you are standing at the edge of the Pontic steppe, where the Bug-Dnieper estuary melts into the Black Sea, there are three islands on the horizon. It can be difficult to see in the haze of late summer, which is when I was there last with two friends, Sam Holzman and Phil Katz.

Foremost is Berezan, once connected to the adjacent mainland. Long and flat-topped like a container ship, the largest of the handful of islands to rise from the Black Sea. It was settled by Ionians in the sixth century BCE, and has been all-but-continuously excavated since 1894.

A second island is artificial: across from the mainland town of Ochakiv lies the fortress isle of Pervomaisky. The Ottomans used the citadel at Ochakiv to control access to the river until it fell to John Paul Jones in service of the Empress Catherine in 1788. Pervomaisky was built up from a sandbar and fortified by Russia in the late nineteenth century. Both permanently blocked off the Dnieper as an invasion or slaving route to the forest steppe.

Far in the distance lies a third, positioned 20 miles off the mouth of the Danube. This is Zmiinyi, or the Isle of Snakes. You can get to Berezan, but Zmiinyi has been closed to visitors since the nineteenth century. You will never visit Snake Island.

Figure 1: Snake Island (Zmiinyi), Ukraine. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0.

Snake Island was in the news this week. On February 25, it was shelled by the Russian Navy, supposedly killing 13. A few days later, it now seems the Battle of Snake Island resulted in surrender and no casualties. But the story had its uses: Ukraine’s President, Volodymyr Zelensky, declared them Heroes of Ukraine for giving up their lives to defend even the bleakest rock.

Perhaps the island attracts exaggeration. There is no fresh water on Snake Island, and aside from its garrison, no residents. There are no trees. Up until the 1950s, it was notably one of the last refuges of the Mediterranean monk seal in the Pontus. In his Periplus of the Euxine Sea, Arrian would claim the birds kept Snake Island immaculate, sweeping it with their wings; anyone who has ever been to remote offshore islands would know better. Snake Island was the White Island (Λευκή) to the ancient Greeks, perhaps reflecting the presence of the birds; in modern Greek (Φιδονήσι), Russian (Змеиный), Ukrainian (Змії́ний), and Romanian (Şerpilor), its name is decidedly less welcoming.

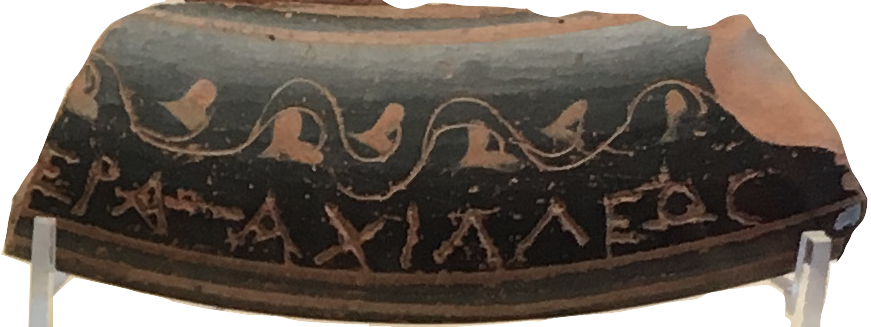

Figure 2: Inscribed sherd from Leuke. Odessa Archaeological Museum. Photo courtesy of the author.

Classicists know Snake Island pretty well. As Mateusz Stróżyński wrote a few days ago, we have copious textual attestation for the White Island in antiquity, where Thetis took Achilles and Patroclus to live undying days. Arrian notes Achilles’ kindliness towards sailors, and indeed, Leuke was home to one of several Achilles sanctuaries that marked the approach to Olbia, the great ancient Greek city of the Bug-Dnieper region.

These sanctuaries for the son of Peleus were “beacons,” in the words of the Ukrainian archaeologist Alla Bujskikh, and took on a decidedly cosmopolitan character. They attracted merchants from across the Mediterranean, who left coins and inscribed ceramics as votives. The Olbians appear to have even erected a small Ionic temple from a relatively early point, albeit destroyed in 1843 when Russia reused its remains to build an (actual) lighthouse on the same site. No archaeological work has taken place on the island since.

Together, the two islands Zmiinyi and Berezan — both in Olbia’s orbit — served as points of arrival and departure for mariners entering the Bug-Dnieper estuary for millennia. Over a thousand years after Greeks had colonized Berezan to gain access to trade with nomads on the mainland, Varangian traders had settled the island as a waystation along the route between the distant north and Byzantium.

Of the two, Snake Island has sat in contention longer. After the Axis-aligned Romanians seized the island during World War II, the Soviet Navy flattened it; they would later build their own radar station there. If the end of the age of sail deprived Snake Island its position at the convergence of the major premodern sailing routes along the Black Sea coast, it continued to be useful in controlling access to the Danube. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the fate of the island was arbitrated between Romania and the newly-independent Ukraine; Ukraine was awarded the island, which it guarded fastidiously, whereas Romania continued to control the territorial waters off its coast. That arrangement held until the day the Russian Navy returned to Snake Island.

“Similarity,” Peregrine Horden and Nicholas Purcell write, “has often been found to mask profound underlying discontinuity.” The routes that Snake Island once commanded are no longer how people get around in the Black Sea; Snake Island mattered in the Ukrainian national imaginary as a message that its soldiers would die to defend every clod of earth.

This uneasy coexistence of archaeological remains in the combat zone should be enough to keep classicists and archaeologists watching this from afar nervous. Despite occasional tensions, Ukrainian and Russian classical archaeologists inhabit the same intellectual tradition; they mostly publish in the same language and have collaborated at sites like Berezan even through the conflicts of the past decade. But at this very moment, some Ukrainian archaeologists who routinely publish in Russian journals are in mortal peril. On the other side, Russian academicians have come out against the war.

The logic of the nation will force them to take sides. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 saw the Russian Academy of Sciences dispatch archaeologists to excavate in the newly seized territory — sometimes excavating in sight of the conflict zone. Putin stages photoshoots of himself at archaeological sites. As Ukraine and Russia are severed from one another — whether by reckless NATO expansion or merciless aggression on Putin’s part — archaeology will inevitably be drawn into the gap. Russia has long had its own exceptionalist narrative claiming direct descent from ancient Greece via its Black Sea colonies. Since 1991, Ukrainian and Russian ultranationalists have tangled over who has priority over the medieval past, with each side fetishizing its most regressive aspects. Cultural heritage mobilized in this fashion puts a target on its back. Losses so far have been incidental, but this might not be the case going forward.

Russia and Ukraine did not go to war because of antiquity. But Snake Island’s presence in the story of the war is an ominous early sign.

Figure 3: Panorama of the Bug estuary seen from Olbia, facing east, September 2017. Photo courtesy of the author.

Authors