Sarah Bond

January 16, 2017

In Roman Gaul, a large map of the known world stood on display at the school of rhetoric at Augustodunum (modern Autun). Around 300 C.E., when the school had fallen into disrepair, a man named Eumenius made a pitch to the Roman governor to allow him to rebuild the structure with his own money. He put particular emphasis on the importance of the map:

"In [the school’s] porticoes let the young men see and examine daily every land and all the seas and whatever cities, peoples, nations, our most invincible rulers either restore by affection or conquer by valor or restrain by fear. [They can] learn more clearly with their eyes what they comprehend less readily by their ears…" (Eum. Pan. Lat. XI.20, trans. Talbert).

It was as clear to Eumenius as it is to modern teachers that students respond well to visual aids. Then as now, students more easily understand the world, their studies, and their place within the cosmos with the help of a good map.

Augustodunum as visualized by the Pelagios Project’s Peripleo. Tiles by AWMC-UNC (CC)

Maps are a special kind of storage, a visual Tupperware to organize, label, and preserve literary and archaeological data, be it the Gallic places mentioned by Caesar, the Germanic peoples cited by Tacitus, or the poleis listed on the trophy erected after the battle of Marathon. And when students not only look at maps in a portico or on a screen but build maps themselves they engage actively with classical texts and remember them better within their Mediterranean contexts.

I am an editor for the Pleiades Project, which digitizes and makes freely available the geo-data that was published within the enormous (but rather expensive) Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World (Princeton University Press, 2000). The Barrington Atlas is a great achievement, but it is not accessible to everyone. With Pleiades one can now download every point from the Barrington Atlas in a number of file types and then use this data for teaching, research, or personal exploration.

Screenshot of Pleiades.stoa.org, which digitized and then added to the locations in the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World.

Pleiades is a wonderful (and free) database, but how can it best be used in the classroom environment? Digital humanities projects are rarely developed with students, and good pedagogy, in mind—which is odd seeing that K–12 and college teachers are the ones who usually use them. Do we think of projects as less important if the focus is on students rather than on tackling “new” research questions? Can’t digital humanities projects do both?

The Ancient World Mapping Center has begun to disseminate free maps for classroom use. Ryan Horne at AWMC launched a program called Antiquity À-la-carte which allowed anyone to take Pleiades points and add them to a map and download, print, and share freely under a Creative Commons license.

With the help of Dr. Horne, the AWMC, and Pleiades, I have begun to develop adaptable modules for students to read texts, learn about basic GIS (geographic information systems) approaches, and then to build their own interactive maps. Both in my classes and in Pleiades-based mapping workshops I have given around the country, I start with a text, and then ask students to visualize it in a kind of geographic remix: Procopius’ discussion of the plague of Justinian, the routes used by Spartacus and his troops in the Third Servile War, or perhaps the travels of Saint Paul as depicted in Acts. Students work through the text in teams, so, as with digital humanities itself, we are modeling to our students the benefits of collaboration and shared data.

The first module posted on the Pleiades site is about the routes of Spartacus, and more are coming in the months ahead. For information about hosting one of these free workshops with me or another Pleaides editor, please send me an email. If you want to know more about the many ancient geography resources online, I have even put a resources page up on my website.

Screenshot from sarahemilybond.wordpress.com of ancient geography resource links.

Archaeologist, geographer, and British army officer T.E. Lawrence (i.e., Lawrence of Arabia) once remarked that “the printing press is the greatest weapon in the armory of the modern commander.” This was as true in 1450, when the printing press disseminated new maps and information across Western Europe, as it would be during the Arab Revolt of 1916. I’d argue that digital tools such as interactive, classroom-made maps can be used as similarly effective weapons in the arsenal of any teacher.

This post is an edited version of a talk given at the 2017 meetings of the Society for Classical Studies in Toronto.

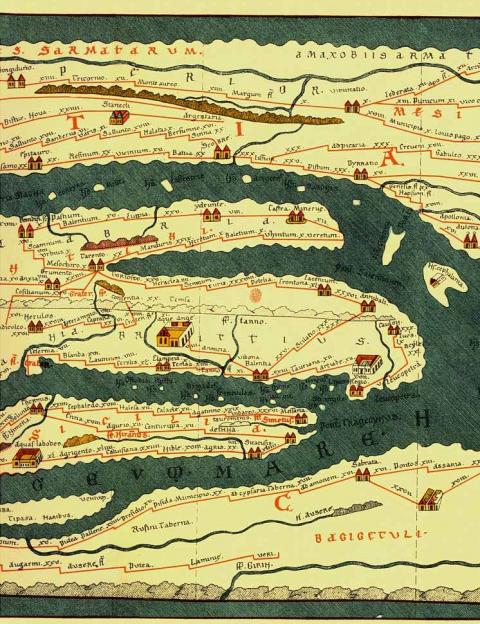

(Header Image: Detail of the Tabula Peutingeriana—top to bottom: Dalmatian coast, Adriatic Sea, southern Italy, Sicily, African Mediterranean coast. From the Bibliotheca Augustana. Public Domain {{PD-1996}})

Authors