Janet Jones

July 3, 2019

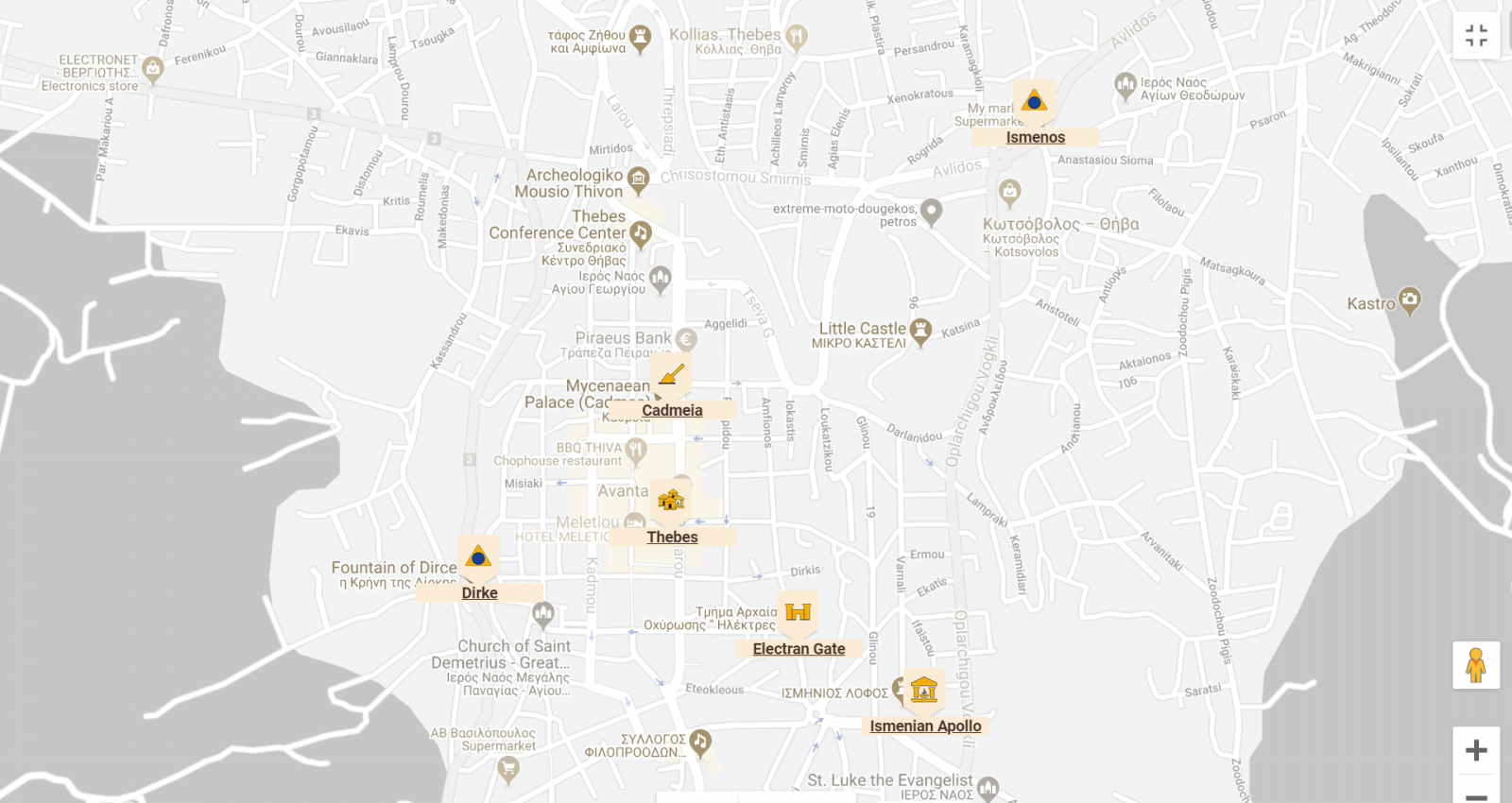

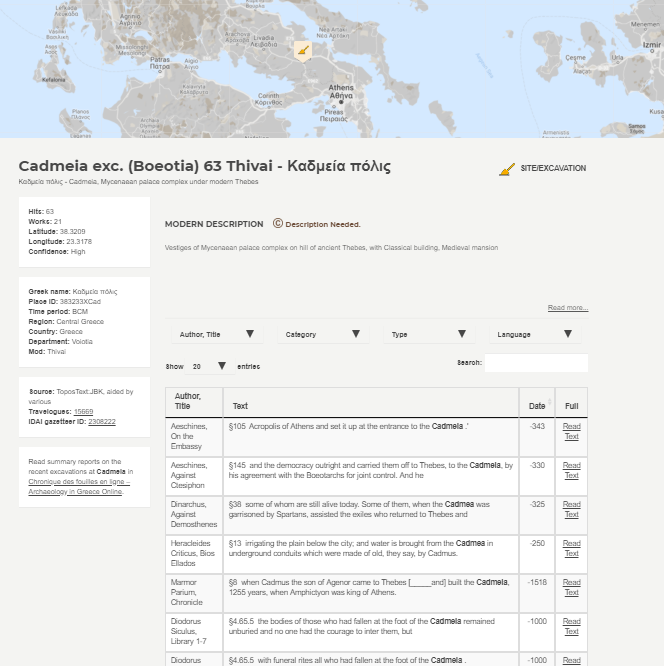

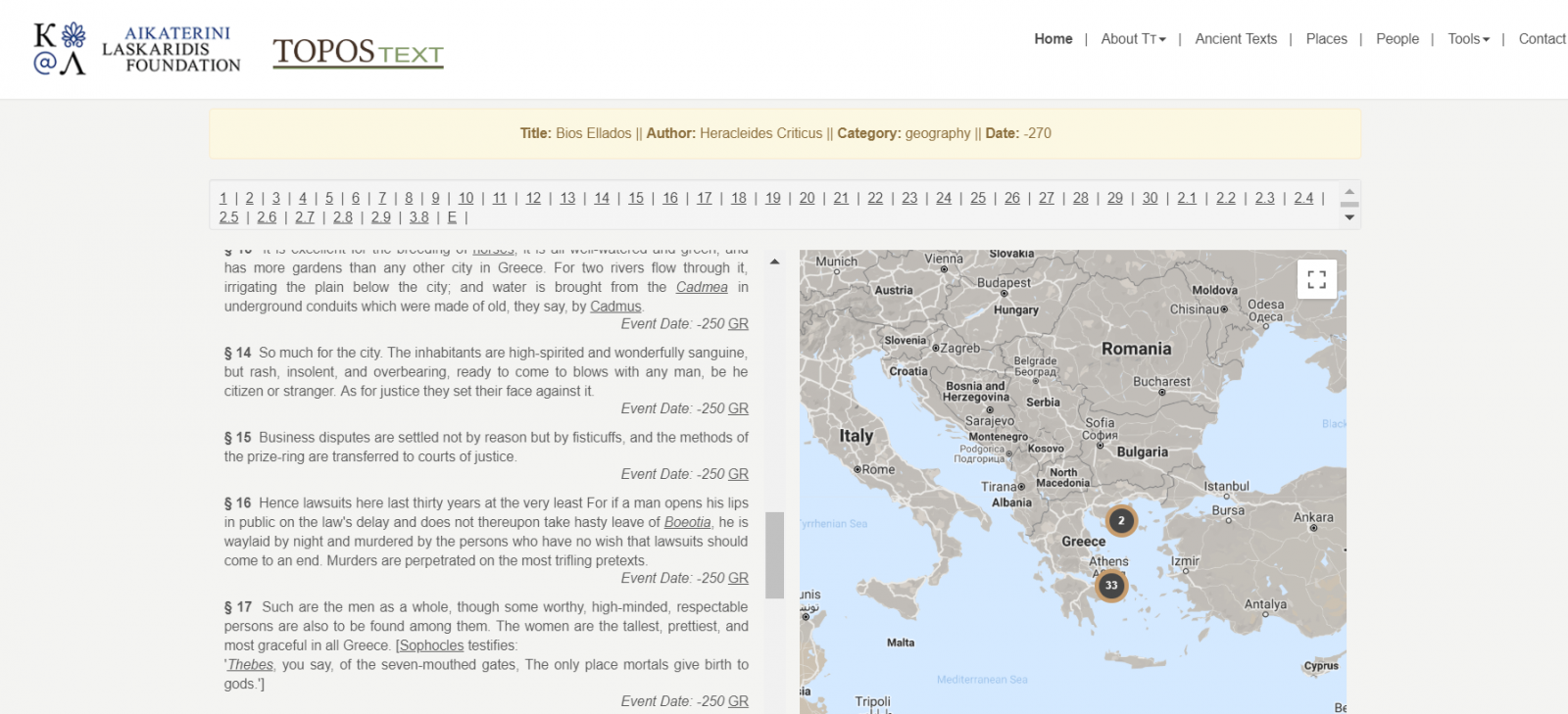

ToposText is a set of tools that projects the geographic elements of ancient texts onto a mapping of the ancient world. Users can follow a classical reference from place-to-text, or from text-to-place. Zooming in on Thebes and clicking on “Cadmeia,” for example, takes us to 63 text entries, such as the Bios Ellados of Heracleides Criticus; clicking on Bios Ellados takes us to 36 map locations through 78 text references. The text is displayed in public-domain English translation (default) with a link to the original ancient Greek (in this case, at Bibliotheca Augustana). The places are located through a Google Map interface.

The guidance on the ToposText site notes that it is designed as an application for mobile devices to allow the traveler on the landscape to “select and read the passages in ancient literature that give a place its historical and cultural meaning.” The app takes the user’s location from the device to provide a map of nearby ancient locales, with icons to indicate the types of places (sanctuary, city, quarry) and a tally the number of references in ancient sources.

According to the About the Project page, the principle creator of the website, Brady Kiesling, took inspiration for its creation from the hope that such a resource would a engage a particular kind of historically oriented traveler (perhaps the very kind that he seems to be). His goal was to create “a tool for finding connections between classical literature and the landscapes that inspired it.” This impetus was supported by the fortuitous expansion at the same time of online mapping tools and of databases of ancient sources. While primarily meant to provide comprehensive coverage of literary references to sites in Greece, ToposText includes major sites in Cyprus, Asia Minor, Sicily, and South Italy, as well as more remote locations with a significant "literary footprint." The project is funded by the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation.

The project acknowledges, in its introductory material, the importance of the Pleiades Project to the inception of ToposText because its “downloadable database of thousands of ancient place names and coordinates, opened the door to indexing ancient texts geographically, using a map of Greece as the basic interface.” The project also relied on a range of internet sources to provide additional archaeological mapping and geolocation information, and on other scholars who have supplied topographic information. ToposText is closely integrated with Travelogues, a second site supported by the Laskaridis Foundation, where the user can find illustrations of Greece and its antiquities from public-domain versions of early travelers’ works.

ToposText provides an impressive compilation of references to ancient sites and modern excavations in a form accessible to travelers. And while, in its introduction, ToposText projects a romantic view of its user being a hiker arriving slightly out of breath at a remote hilltop site, ToposText is also an excellent tool for the scholar/researcher in their office. The desktop experience is different in kind—and quality—from the app. On the larger screen the engaging interfaces of the website are on full display, drawing the user in to wander the digital landscape.

The link between topography and text is unforced in ToposText. Texts and maps are integrated but distinct, so that the explorer can enter texts through the map or enter into the landscape through a text. (Entering via historic personages is a third option, leading into texts and thereby into maps.) This integration of place and text avoids the old pitfalls of texts without context and provides a richness that is lacking when considering each in isolation.

For all its richness, or perhaps because of its richness, ToposText gives the sense of a resource still finding its way. As an intellectual tool, it lacks a degree of coherence, perhaps because its coverage is so constrained by the accidents of text preservation. Filters permit the explorer to select specific types of features—mines, towers—but these slices of the already-limited dataset are idiosyncratically sparse: four baths are mapped in Asia Minor, three of them on islands offshore of Bodrum.

As a geographical tool, ToposText bears constraints born of its presentation. “Topography” is used in the sense that classical archaeologists employ, a precise description of position and relation. The geographer’s “topography”—the three-dimensional landscape across which settlement is draped—is not shown on the map (although aerial photo imagery is). Another inherent constraint of the georeferenced database—the conversion of place names to latitude-longitude pairs—is that the places of interest are punctiform. A city is a point, which seems appropriate at a regional map scale, but misleading at larger one. Some results are comical—the entire ancient kingdom of Lydia is mapped into an olive grove behind the village of Mersindere.

The fabric of the ancient world will be unattainable by this type of tool without better representation of the linear features—roads and streams. A strength of well-made ancient mapping—e.g, Talbert’s majestic Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World—is the reconstruction of the landscape as network, showing what places were joined most directly by ancient roads. A further impediment to the usefulness of the ToposText maps for exploring ancient landscapes is how the interface is dominated by space to the exclusion of adequate attention to time. All sites, as one encounters them on the map, are collapsed into a single cartographic moment—a unitary historic time. The Bronze Age and the Late Roman are visually identical. This matches the worst tourist experience, of an archaeological landscape comprising things that are undifferentiatedly “old”; the potential to take time slices of antiquity could be better developed.

These are directions that ToposText can grow, but it is unfair to judge the tool by its potential and not its execution. ToposText expands the utility of the recent florescence of digitized texts by automatically linking them to maps through georeferenced toponyms within them. The concept is powerful—and will become stronger over time. ToposText provides an intriguing way to spatialize texts and “cite” the landscape. Explorers should be grateful for this tool, and look forward to its further evolution.

TITLE: ToposText

DESCRIPTION: Collection of ancient texts and mapped places relevant to the history and mythology of the ancient Greeks

NAME (creator or contributor): Kiesling, Brady

PUBLISHER: Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation; Pavla S.A.

PLACE: Piraeus, Greece

COLLECTION TITLE: none

DATE CREATED: 2015–2016

DATE ACCESSED: April, 2019

AVAILABILITY: Free

RIGHTS (license restrictions imposed on access to a resource): Copyright © Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation

CLASSIFICATION: databases, Greek, linked open data, mapping, mobile applications, outreach, reference materials, texts

Authors:

Janet D. Jones

Janet D. Jones is Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies at Bucknell University.

Ben Marsh

Ben Marsh is Professor of Geography and Environmental Studies at Bucknell University.

(Header Image: Babylon Map of the world. British Museum. Image taken by Shadsluiter and accessed via Wikimedia, CC By-SA 4.0.)

Authors