Javal Coleman

September 10, 2021

Content advisory: this post includes an anti-Black epithet in the recounting of a personal experience.

I have always been interested in history. In high school, I took two history courses that drew my attention to the field. One was required, the typical AP U.S. History, and one was an elective, AP European History. Both courses involved the discussion of slavery and how it affected the development of different world powers. I was not interested in the rise of nations or how they acquired power. The individuals who were used, abused, and marginalized are what I find fascinating about studying history. From high school, my path was clear: study history and, more specifically, study the history of slavery.

When I began my undergraduate career at the University of North Texas, I was not sure what period of history would keep my attention. I enjoyed American history, but I was not sure about it as a major focus. I liked the study of European history, but “everyone’s a WWI and WWII specialist these days.” I wanted to do something different, something I’d never heard of. One of the major courses was a basic survey of World Civilizations. It was in that class where I was first introduced to the histories of Greece and Rome. To be clear, I had heard of these entities in various media, such as Zack Snyder’s 300 and Disney’s Hercules. But I’d never considered them as actual areas I might study. Up until that point, no one of influence had mentioned either Greece or Rome to me.

After a course on the Roman Republic, I quickly became enamored with the study of the ancient Greco-Roman world. I took as many classes as I could, keeping my eyes out for slavery in any contexts—including the courses I took in American History. This took the shape of a few different seminar papers focusing on Roman slave markets and slave law, a Word doc of every mention of slaves in Petronius’ Satyrica, and a few projects involving comparative slavery between the United States and Rome. I enjoyed every minute of this work, though much of it was difficult—especially reading about the sufferings of enslaved individuals throughout time. But something that I never stopped to ask myself is why? Why slavery? Why am I interested in studying such a brutal and inhumane institution? Undergraduate Me never stopped to really process these questions. Rather, I pressed on and wrote about marginalized individuals in a marginalizing way. I treated them simply as subtopics instead of human beings. Humans with feelings, anxieties, and histories. I let the nature of the ancient evidence dominate my thinking.

But I still needed to answer a crucial question. Why am I so interested in the study of slavery? Well, after some time of thinking and meditating about my life and my own experiences, the answer was right in front of my face: I am the descendant of enslaved individuals! I come from the people who were used, abused, and marginalized. And I have been marginalized. There is something about the attempt to recover the enslaved voice that feels deeply personal as an African American. My interest in the history of ancient and modern slavery is an interest in enslaved individuals. A deep yearning to understand feelings that are lost, yet somehow tangible.

I was being told what kind of questions to ask by older white men. Generations of scholars who have been able to distance themselves — if only in their minds, not in reality— from enslaved individuals as people. The desire for historical “objectivity” has led many scholars over the years to miss what, in my mind, is the larger goal of the study of slavery: deep engagement with the individuals harmed and destroyed by that vile institution. But I have also realized that this is not enough—or, rather, that part of that process should be a reflection on one’s own circumstances and a thorough examination of the modern discourses of power that sprang from the relationship between enslavers and enslaved. In other words, I strongly believe that my job in the study of slavery both modern and ancient is not to supply voices, but to be still and hear them when they speak. I owe it to them to let them speak for themselves rather than to try and supply something for them out of guilt.

This concept has been fleshed out eloquently by American historian Walter Johnson in his seminal article “On Agency.” Like Johnson, I believe that the job of the historian of slavery is to listen rather than to speak for enslaved individuals. The study of slavery can teach us much about the systems of oppression and hierarchical structures of our own time. From studying slavery, we can understand not only a multi-faceted inhumane institution that has persisted across ages and cultures, but also the racial tensions inherent in our modern discourse. In other words, studying slavery can shed light on some of the modern socio-political issues of today’s world. For me, understanding the legacy of the enslavement of my ancestors — of people that look just like me — is crucial to understanding the debates, violence, and tensions that are very much alive today.

A scholar whose work really embodies this kind of work is that of Saidiya Hartman. I am thinking of her article “Venus in Two Acts,” for example. In this work, Hartman imagines the experience of enslaved women in the Atlantic world. She examines different episodes of violence against enslaved women and discusses what we lose from the current state of the archive. Hartman expresses frustration at the fact that we don’t have more to say about these women except that they were victims of violence. She imagines what it would be like if we knew more about their lives. How disappointing it is that the violence of the archive results in the destruction of lives, the loss of stories. Hartman discusses the temptation to fill in the gaps of these lost stories. Her work is inspiring because she attempts to imagine closure where there is none. It tries to understand and recover lost feelings—something that historians of slavery would do well to consider.

One of my most virulent memories of racism comes from my early childhood. I was about twelve years old. When I was walking down the street, a few white guys drove down the street in a pickup truck and threw a bottle at my back and, as they drove by me, yelled “FAT NIGGER,” and continued to drive. Besides the pain I felt from that bottle hitting my spine, I felt emotional turmoil. I felt as though I could not move. Tears were streaming down my face, and I stood there for what felt like forever. As I arrived back home, I chose to say nothing. I was afraid to speak about it. Afraid that maybe something worse might happen, or that I would somehow run into them again. I swore an oath that I would not tell anybody about what happened that day.

An oath that I have finally broken.

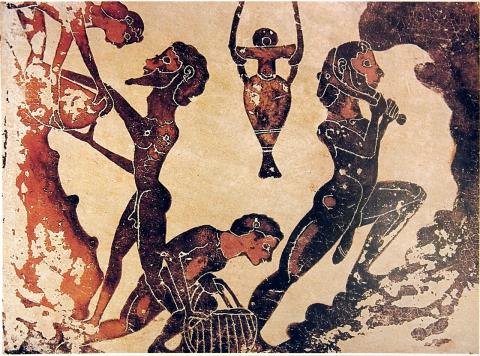

Header image: Corinthian black-figure terracotta votive tablet of slaves working in a mine, late 7th c. BC.

Authors