Nina Papathanasopoulou

June 26, 2020

The new Classics Everywhere initiative, launched by the SCS in 2019, supports projects that seek to engage communities worldwide with the study of Greek and Roman antiquity in new and meaningful ways. As part of this initiative the SCS has been funding a variety of projects ranging from reading groups comparing ancient to modern leadership practices to collaborations with artists in theater, music, and dance. This post centers on projects that promote emotional well-being and use Greek texts to facilitate conversations on current social justice issues, from New York to Chicago and San Francisco.

Through the Classics Everywhere initiative the SCS has funded 74 projects, many of which seek to bring diverse and underrepresented voices to the fore of discussions in and about Classics, creating opportunities for the development of new interpretations and approaches to the field. This post focuses on three projects that bring together collaborators from diverse backgrounds and experiences, with an emphasis on the promotion of social justice, emotional well-being, and the cultivation of empathy. Each uses Classics to address how we can understand another’s feelings and point of view.

In her research and in teaching, both at Rutgers and in medium and maximum security prisons, Emily Allen-Hornblower, Associate Professor of Classics at Rutgers University, has always been struck by the central role of emotions in Greek epic and tragedy. Their ability to engage diverse audiences led her to conceive an innovative project about how the Greeks can help us understand the role of emotions in our lives — particularly their cognitive component. The project, supported by a Whiting Public Engagement Seed grant, the Just One Foundation, and Classics Everywhere, consists of a series of public conversations with actors, formerly incarcerated men and women, and the public at large. Each session is centered on one or two central emotions – such as shame, fear, anger, grief, and compassion – and begins with a performance of an excerpt from Greek tragedy by seasoned theater actors. Allen-Hornblower then moderates a conversation with her formerly incarcerated student, the actors, and the audience, using the emotions as a window onto the human heart and an opening for each of us to recognize the universal traits we all share.

Allen-Hornblower was able to hold four two-hour events before COVID-19 brought her project to a temporary halt – at the New York Society for Ethical Culture and the Players Club in New York City, in the mental observation unit of Rikers Island Jail, and at Howard University in Washington, D.C. During these events, she engaged in a back-and-forth conversation about the plays with Marquis McCray, a man who spent 28 years in prison in New Jersey, where he took courses in history and literature with Allen-Hornblower. Their exchanges highlighted his reception of the tragedies, and engaged the audience in a reflection on the pertinence of the ancient material to his and all of our lives — including life during, before, and after prison, in an era stained by mass incarceration.

Figure 1: Emily Allen-Hornblower and Marquis McCray at the New York Society for Ethical Culture on October 10, 2019. Photo by William Wheeler.

Tragic characters find themselves in extraordinarily difficult circumstances and face devastating crises. Their emotions and actions are key to understanding human psychology and behavior. What pushes characters like Philoctetes and Heracles to isolation or violence? How much grief can the enslaved Andromache and Hecuba endure, and how do they persist in the face of desperate circumstances? Can one action define a person’s “worth?” What happens to someone if you treat them poorly, marginalize them, and take away their voice? Is anger not a justified form of righteous indignation? These questions provide a platform to facilitate conversation regarding the Greek tragedies and how their characters and themes (their fallibility, vulnerability and humanity) resonate with the incarcerated in our day. Over the course of their exchanges, Allen-Hornblower and McCray inspired discussions on social justice, education, and systemic issues in our society.

Figure 2: Tabatha Gayle as Andromache during the performance at the Players Club on November 11, 2019. Photo by Al Foote III.

Allen-Hornblower aims for conversations that mirror the ancient works at their center: neither of them is ever explicitly moralizing or didactic. The events are not about how anyone should act or feel, but about providing a space for people to express and acknowledge the legitimacy of emotions, through discussion of the characters under scrutiny. In Allen-Hornblower’s words:

The project harnesses the power of Greek drama and epic to help us understand human emotions through storytelling. It utilizes that understanding to connect us to each other and the world around us, and to foster a sense of community and belonging for all.

On the opposite side of the country, Alexandra Pappas, Associate Professor and Director for the Center for Greek Studies at San Francisco State University (SFSU), also uses Greek texts as a tool for discussing human emotions and challenging experiences. On March 2 she organized a performance called Conversations with Homer, a series of first-person songs that capture the horror, grief, and love that permeate Homer's epic poem and the combat experience. The event aimed to build bridges between the local and the academic community; the humanities and the arts; the ancient and the modern. With the support of the Classics Everywhere Initiative, a number of humanities and arts programs at SFSU, and the V.E.T.S.@SFSU, a student group comprised of war veterans, Pappas was able to bring together a broad range of artists to collaborate in creating an original work based on Homer.

The creators she brought together for the project included: Joe Goodkin, a Chicago-based singer and songwriter whose 16 song-version of the Iliad, The Blues of Achilles, was used as the basis for the performance; Ellie Falaris Ganelin, founder of the Greek Chamber Music Project (GCMP), who re-arranged Goodkin’s songs for a chamber music ensemble and played the flute; Ariel Wang, violinist and vocal singer; Lewis Patzner, a cellist and composer from Oakland CA; John Mavroudis, the Greek-American artist who illustrated the event’s poster; and a number of SFSU students. The students translated short passages of the Iliad and the Aeneid, and also created new poems and art exploring Iliadic language and themes. During the performance, the SFSU students’ translations were projected on a backdrop behind the performers.

Figure 3: The poster made by Greek-American artist, John Mavroudis, for the Conversations with Homer event on March 2. Photo used with the artist’s permission.

All collaborators were asked to respond to the themes of the Iliad, with a special focus on Book 18: Achilles’ grief and wrath at Patroclus’ death, and the manufacture of his famous shield. Book 18 was also the subject of “Greek Epic”, one of Pappas’ courses during the spring semester, and so her students’ involvement in this project was part of their course.

Figure 4: A page from the poetry and art book of Erik Baldwin ’20, one of the student creations made as a response to the Conversations with Homer event.

Goodkin’s adaptation of the Iliad focuses on the grief rather than the wrath of Achilles; the grief Achilles feels and the grief that he causes. For Goodkin grief stems from feelings of love: “the more you love something, the more you grieve when you lose it.” The 16 songs that make up The Blues of Achilles are presented in reverse chronological order, starting with a song about Achilles and Priam, and moving backwards in time from there. By presenting the ending to his audience first, he invites them to think about the places where the situation could have taken a different turn.

In re-arranging Goodkin’s songs for the chamber music ensemble Ganelin hoped “to add another dimension to the music and to heighten the emotion.” The female voices of the poem were also amplified by having vocal singer Wang sing all the female parts. A sample of the songs performed at SFSU on March 2 can be found here. “It's amazing that an ancient story like the Iliad has the staying power to be relevant today and to continue to be a muse for creative expression,” Ganelin said.

Pappas’ main aim was to highlight the Iliad’s relevance and accessibility to contemporary audiences of diverse backgrounds:

To me, one aspect of great art is its generative power. Another is its ability to touch an audience in diverse ways. With this in mind, I was keen to see what kinds of verbal and visual art Homer's poetry could inspire our students to produce, and what kinds of new compositions professional musicians might generate in conversation with the text.

One of the SFSU students who attended the event, Alberto Pimentel ’20, gave a moving testament to the power of today’s artists to facilitate emotional healing through ancient epic:

My grandmother, my family’s pillar, had just passed away and having the opportunity to attend SFSU’s Center for Greek Studies’ Conversations with Homer seemed to me wholly necessary. This event led to the catharsis that we simply had not had after a tormenting week of having suddenly suffered the inevitable. It was Joe Goodkin’s sensitivity, combined with the musical variation and harmony that his folk-style employs, that permitted Homer’s oral tradition to be encapsulated, particularly regarding themes of his epic, which may be some of the more pervasive realities of war writ large. The performance had my mom and I in tears as we thought of my grandmother, as we thought about war, as we thought about history, and as we remembered that we are all, as the chorus sang, “bone … blood … [and] flesh/That somebody loved.” Everyone in that theater conversed not just with Homer but with some of the deepest and thus most universal thoughts and emotions driving humanity.

Inspired by such events and by a panel promoting inclusivity in Classics during the SCS annual meeting in Washington, D.C., David Tapper, a high school junior at the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, planned a Greek mythology workshop for Social Justice Week 2020, a week his school devotes every April to issues of social justice. Tapper has been studying Latin since his freshman year and attended the SCS annual meeting to participate in the Committee on Ancient and Modern Performance (CAMP) production of Cato. In his workshop, which had to be conducted via Zoom, he focused on reinterpreting classical mythology through a contemporary lens. Participants read the myth of Demeter and Persephone and were encouraged to retell the myth through a modern perspective: one group cast Zeus and Hades as members of the terrorist organization Boko Haram who kidnapped 276 school girls in 2014, while another discussed the separation of Demeter and Persephone in comparison to parents and children being separated at the US-Mexico border under the Trump administration. The workshop concluded with a conversation on women’s rights and social injustices more broadly, fulfilling Tapper’s goal: to show the continuing relevance of Classics and use ancient stories as a gateway to discuss social and political situations where oppression and marginalization exist.

Figure 5: The flyer for David Tapper’s workshop inviting participants to reconsider the ancient myth of Persephone and the gender stereotypes embedded within it.

As the above projects illustrate, the study of Greek literature and mythology can be used as a tool to explore shared experiences, to amplify the voices of those cast aside and kept silent, and to think critically about social injustices ingrained in our society. Though the study of Classics has been misused by white supremacists and nationalists, projects like these point to the compassion and sympathy that one can elicit from engaging with the ancient Greeks and to a deeper understanding of our humanity. At the end of the Iliad the poem underlines the possibility of shared compassion even in circumstances where reconciliation seemed impossible: Achilles expresses empathy for Priam’s afflictions (24.518) and both feel enjoyment gazing at each other (24.628-33). The two even clasp their hands (24.671-72).

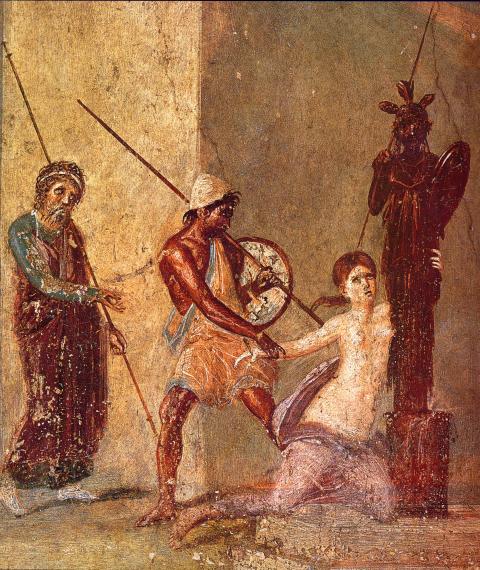

Header Image: Scene from the trojan war: Cassandra clings to the Xoanon, the wooden cult image of Athene, while Ajax the Lesser is about to drag her away in front of her father Priam (standing on the left). Roman fresco from the atrium of the Casa del Menandro (I 10, 4) in Pompeii.

Authors