Adrienne Rose

July 12, 2018

When you do study abroad trips with college or high school students, teaching happens on-site and draws upon the artifacts that surround you. We found this out firsthand while leading the first ever 3-week study abroad summer session in Greece from 21 May to 12 June for the University of Tennessee-Knoxville’s Classics department this summer. I co-led the trip with classicist Thomas Rose. We both specialize in different areas, which really gave breadth to the teaching. Whereas Prof. Rose is an expert in Greco-Roman historiography and epigraphy, I specialize in poetry and translation while teaching at the University of Iowa. The itinerary was loosely inspired by the trips we both took to central and northern Greece as regular and student associate members of the American School for Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) in 2012 with our Mellon professor, Margaret M. Miles.

We had 11 undergraduate UTK students with us. A few students are majoring or minoring in Classics/Latin, but also a range of majoring in Theatre, Anthropology, English, and Biology. They enrolled in general education Classics courses, such as Greek and Roman Civilizations, which sparked their interest in Classical antiquity and curiosity about the history and topography of mythological tales as well as modern Greek culture. They needed to see Greece with their own eyes. For the full itinerary and photo documentation of our trip, please follow our Facebook page UTK Classics in Greece.

Image by Adrienne K.H. Rose and used by permission.

We began our first instructional day in Athens by walking up Lykavittos hill in the early evening for a 360-degree panoramic tour of Athens and Attica. On the way up, we took a break from the switchbacking stairs to talk to students about rock-cut inscriptions and horos boundary inscriptions.

“Horos” (“horoi,” plural) can mean “boundary” or “watcher” in Ancient Greek. While horoi didn’t always indicate a property line, it could also mark its general location, secure land from encroachment or violation, and protect real estate from creditors (Athenian Agora XIX ). Horoi could delimit sanctuaries — there is an Athenian decree naming Athena Horia and Zeus Horios as boundary protectors — as well as prohibit people from leaving their trash in certain places, a kind of ancient “no dumping here” sign. It is also forbidden by law to move another person’s horos (Plato, Laws 842E-843A). There are horos steles in situ and in the museum of the Athenian Agora, as well as in the Acropolis museum. More on this below.

Image by Adrienne K.H. Rose and used by permission.

Rock-cut inscriptions were mostly carved by shepherds in bedrock. There are countless rock cut horoi on Mt Hymittos, and at least one on Lykavittos. Together with the students, we clambered up a low, cacti-covered cliff and one by one students climbed up, brushing aside pine branches, placing their feet carefully to avoid the pointed edges of agave. The inscription appears in a vertical orientation. Students were able to locate, identify and read the inscription, tracing the ancient letterforms with their fingertips. I noted the lunate sigma, an indication of very very old letterforms dating to the early 6th century BCE. “Cool,” they said, jet lagged and sweaty from the heat and climb, and we continued up the hill.

Image by Adrienne K.H. Rose and used by permission.

Horoi inscriptions, as well as olive oil presses, well caps, spolia, and ubiquitous architectural features, became touchstones throughout the trip. In the Athenian Agora the next day, one student noticed a horos in situ. “Hey, it’s one of those boundary stone things!” This particular stele not only marks a location, but also speaks: I am the boundary stone of the Agora.

Horoi have intrigued me ever since a small group of friends went hunting for them on Hymettos when we were student members at the ASCSA. Relying on Dr. Merle K. Langdon’s Hymettiana publications, which include detailed maps with GPS coordinates, we were able to locate and identify three or four rock-cut inscriptions. Epigraphy allows us to recreate and delineate ancient space in pivotal ways.

As a scholar and teacher of translation, horoi are also compelling to me because delimiting space implies shared boundaries and a sense of coexistence and hospitality, whether sacred or secular, topographical, national, linguistic, commercial, or personal. Translating these inscriptions on site and in various Greek musea turned out to be a spectacular way to experience with students a memorable study abroad session, and in the process, to discover both ancient and modern limits.

Image by Adrienne K.H. Rose and used by permission.

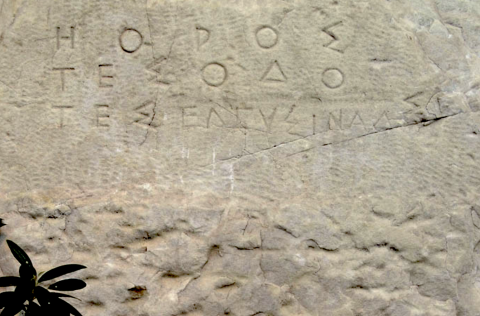

Header Image: Boundary marker delineating the limits of the Sacred Way in Athens, ca. 520 BC. At the end of the 5th century BC, the original inscription was replaced by the words: ΗΟΡΟΣ ΤΕΣ ΟΔΟ ΤΕΣ ΕΛΕΥΣΙΝΑΔΣΙ, "Boundary stone of the road to Eleusis" (Image via Wikimedia under a CC-BY-SA 2.5).

Authors