Ashli Baker, Katherine Beydler, and Elizabeth Manwell

July 25, 2022

This is Part 2 of a three-part series. Find Part 1 and Part 3 here.

Only by abandoning traditional grading and performance assessment practices can we achieve our ultimate educational objectives.

Tradition in Classics is powerful. When the three of us started teaching as graduate students, we drew on our experiences as undergraduates in the many Classics courses we had taken, particularly when it came to assessing students. This is not a bad thing! We all need to start somewhere while we are growing as educators. Nevertheless, it was difficult for us to imagine, for instance, teaching Latin without traditional assessment practices (such as high-stakes tests), because that’s how we were taught.

What we came to feel over time, however, was that practices that, to us, felt “natural” and right and necessary, even, were problematic for a significant number of students, and we were losing them over the course of the semester or year. What’s more, it felt like traditional grading — based on an instructor’s model outcome, which is, at times, unavoidably subjective — flew in the face of the growth mindset we were simultaneously trying to instill in our students. The greater their distance from our model outcome on day one, the more discouraging our courses were for them.

Thanks to scholars of teaching and learning, our understanding of the impacts of traditional grading on learning, equity, and inclusion is growing all the time, as are ideas for effective, workable alternatives to conventional assessment practices (see our website for some links and suggested readings).

While the three of us have valued experimenting with various approaches, we want to repeat what we said in our first post: our experiences of using these strategies come from positions of racial and institutional privilege and, particularly in terms of student response, may have variable outcomes for instructors with diverse identities. We encourage instructors to prioritize their own wellbeing and consider sustainable, incremental changes.

If, however, you are curious and feel ready to make some changes, what are practical alternatives to traditional assessment?

In this post, we examine the benefits for the instructor and students of one alternative method of assessment that has exploded in use in recent years, “labor-based grading” (LBG) or “contract grading.” I (Ashli) have used this style of grading in my classroom for the last few years for beginning and advanced Latin classes, as well as larger culture courses. I have found that it encourages a growth mindset and risk-taking in students, demystifies grades, turns student focus from grades to learning and achievement of personal goals, allows for better integration of self-reflection, and does not favor students who begin the semester with more experience.

Put simply, LBG is more inclusive and more encouraging while still establishing clear expectations around class work.

On the model of Asao B. Inoue and others, I also approach LBG explicitly from a social-justice point of view, openly explaining to students the tendency of traditional grading to reward those who arrive with more experience and penalize those who arrive with less, an inherently inequitable approach when, for individual and systemic reasons, students have not had the same — or even similar — access to learning, particularly in Classics. There is real value in making this explicit, because research on sense of belonging (e.g., this, this, this, and this) indicates that many students incorrectly believe they are the only ones who lack knowledge or experience with certain subjects.

So, what is labor-based grading?

In LBG, each assignment is worth a specified number of points and, for all assignments completed “in the spirit they are assigned” (so Inoue), students earn the full number of points available, even if there are errors. In other words, students earn points for completing and submitting assignments, rather than on the extent to which the final product is error-free or matches the instructor’s model outcome.

While some instructors might bristle at the idea of giving full credit for work that isn’t error-free, it is important to note that formative assessment — constructive feedback that helps students correct their misunderstandings and see places for growth — is essential in LBG. In lieu of grading every assignment, the instructor, prior to the semester, establishes which assignments will receive instructor feedback, which will receive structured peer feedback, and which will be self-corrected or evaluated. Depending on the number of students in the course, this can be an important decision and can make this approach to grading more (or less) sustainable.

The contract, introduced the first day of class, contains the total points for all assignments for the semester. Some instructors have students create a contract collaboratively with them at the beginning of the semester or, for very small classes, have each student write an individual contract focusing on the areas in which they want to grow. Another approach to LBG has a maximum grade of “B” for the fulfillment of the “basic” contract, but offers additional points for specific “above and beyond” tasks that can be completed by those particularly interested in the subject matter and wanting to do more. It’s worth noting, however, that with this approach, any additional tasks required for a higher grade should be fully articulated at the beginning of the course. (Otherwise, what was envisioned as a more equitable method can quickly become problematic.) Although I’m open to experimentation in the future, up to now, I have always written the contract myself and given assignments that add up to an “A,” offering students the flexibility and autonomy to work to the grade they want based on their priorities and other commitments.

Here is a sample contract that I have used for Roman History:

|

Points |

Assignment |

|||

|

60 points |

Engagement (15 weeks x 4 points) |

|||

|

45 points |

Moodle Quizzes (10 weeks (-lowest) x 5 points) |

|||

|

60 points |

Perusall Reading and Annotations (15 weeks x 4 points) |

|||

|

60 points |

Social Journals (10 journals x 6 points) |

|||

|

30 points |

Self-Reflection (3 x 10 points) |

|||

|

145 points |

Formal Writing (WA1: 25 points, WA2: 35 points, WA3A:35, WA3B: 50) |

|||

|

400 total |

||||

|

|

Total Points |

Grade |

|

|

376-400 |

A |

|

|

360-375 |

A- |

|

|

348-359 |

B+ |

|

|

336-347 |

B |

|

|

320-335 |

B- |

|

|

308-319 |

C+ |

|

|

296-307 |

C |

|

|

280-295 |

C- |

|

|

240-279 |

D |

|

|

0-239 |

F |

As the three of us have experimented with assessment in our classrooms, we have come to better understand the importance of excellent, multidirectional communication throughout the term. Grading practices that are opaque or created on the fly will disproportionately harm students who are unfamiliar with the “hidden curriculum” of college. Transparency, therefore, is essential for creating a more inclusive classroom and demystifying grading.

In fact, even if you are unprepared to implement alternative assessments, you can make your grading — and classroom — more equitable by increasing the transparency of your grading practices. In LBG, for example, students should be able to easily track assignments, and thus points earned and missed, so that they see where they stand throughout the semester. There are many ways of doing this. I, for instance, use a Google Sheet that auto-updates an individual grade sheet for each student, keeping a running total of points that students can access at any moment in the semester. One suggestion for larger classes, for which individual, auto-updating grade sheets would be time-consuming, is to distribute to each student at the beginning of the semester a blank chart with a box for each assignment, by which they can track their own labor throughout the semester. Students could also use a form like this to keep track of how much time they are spending on tasks, which can be helpful for them and for their instructor.

Substantial student reflection, which harnesses metacognition, one of the most powerful tools in learning, is at the heart of LBG. Because LBG aims to increase student risk-taking, investment, and engagement, it is essential that the syllabus includes formal, point-earning opportunities for students to think deeply about their learning.

There are countless ways of doing this. While some use weekly reflections, I have settled on three-times a semester: at the beginning, middle, and end. Students respond to a set of questions designed to encourage them to establish learning goals and self-evaluate whether they are doing the amount and type of labor needed to reach those goals. In subsequent posts, they reflect on their initial response, learning, and areas for ongoing attention and growth. Students have found this very useful, with many sharing that they will start using self-reflection as a way of goal-setting and checking in with themselves in all of their classes. Furthermore, reading their self-reflections has been helpful to me — I can see where I need to address shared challenges with the whole class, how I might support individual students better, and how I can shift certain aspects of my teaching to engage the specific group of students in front of me more effectively.

Another unexpected benefit I experienced when I made the switch to LBG was that it inspired changes not only to my grading but also my overall attitude towards assessment, which previously had relied heavily on high-stakes testing and papers. Because points are based on completion of work rather than accuracy of each assignment, formative assessment takes the place of summative assessment and high-stakes testing is off the table. But what to do instead?

When I started developing an alternative to high-stakes testing in my Latin class, I wanted an assignment that would treat assessment itself as a learning experience, rather than a snapshot of successful test-taking. From this premise, I developed “Comprehension Checks”: two-stage, take-home, open-book Latin composition assignments, in which students independently translate an instructor-generated English passage. In the first stage, students submit a draft, and then I underline errors and offer brief comments directing their next steps. In the second stage, students ask questions, correct their work alone or with others, and ultimately submit a “correction and reflection,” articulating why each correction improves their first draft. Students receive more points for the correction and reflection than the initial draft, further reinforcing learning as a process. The quality of student work and overall learning in this assignment has been dramatically better than high-stakes tests, making it a pleasure rather than a burden to assign, mark, and — according to students — complete.

Even if you aren’t quite ready (or interested) in a radical departure from your current approach to grading, we hope that this series inspires you to think about alternatives we have found effective in creating more equitable and inclusive learning environments.

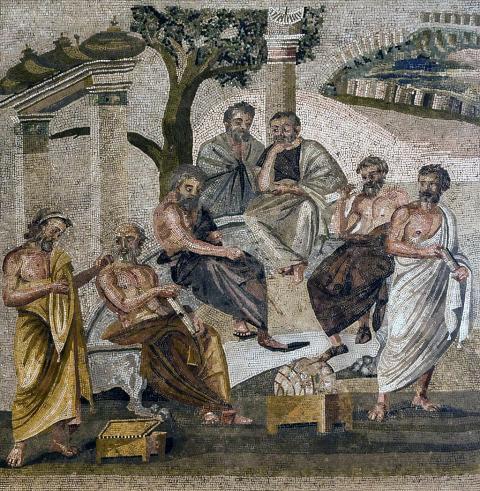

Header image: Plato's Academy mosaic, Pompeii. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Authors