Elizabeth Manwell, Ashli Baker, and Katherine Beydler

August 1, 2022

This is Part 3 of a three-part series. Find Part 1 and Part 2 here.

There is nothing ideologically neutral about grades, and there is nothing ideologically neutral about the idea that we can neatly and tidily do away with grades. We can't simply take away grades without re-examining all of our pedagogical approaches, and this work looks different for each teacher, in each context, and with each group of students.

— Jesse Stommel, “Grades are Dehumanizing”

This quote from Jesse Stommel, long-time proponent of ungrading, offers what we hope to give our students — a conceptual opening and an achievable challenge. If you are thinking about different ways to assess students, you may have heard of ungrading. Your reaction might be curiosity, apprehension, or some combination of the two. But as Stommel states, no two teachers are necessarily going to implement the same assessment strategy in the same way — and the same teacher may choose different approaches in different classes or for different students. But Stommel does encourage two things: to think about what kind of assessment you need to get your students where you want them to go (see our first post all about assessment), and to realize that grades carry with them a history, particular kinds of incentives and disincentives, and are inherently unfair (as he elaborates in this great post about the history and uses of grading).

“Ungrading” is not defined in a consistent way, but can cover a range of alternative assessments, usually focusing on student reflection and decentering of instructor authority. Proponents of ungrading usually share an interest in shifting students’ attention from their performance in the class and toward their learning. We have been experimenting with similar kinds of assessments in our Latin classes, and yet they are not exactly the same. As Stommel says, different teachers, different contexts, different students, different goals, different needs. We say this just to emphasize there is no “right” or “wrong.” Instead, some of the same concerns have shaped our desires to experiment with ungrading, including not only our perception of grading as unfair but also our observation of low student engagement after receiving a “bad” grade. As a result, we have found that our attempts share several characteristics, including:

- A focus on formative assessment

- Multiple opportunities for revision of student work

- No grade or point totals on assessments

- Opportunities for metacognitive reflection on the learning process

- Final portfolio presentation

- Transparency for students on learning goals and why they matter

- Opportunities to complete exams/projects/etc. (ungraded or graded) in groups or teams, as this collaborative work aligns better with daily life in our classrooms

Below we share two different models, which fit the needs of our students. You can use these as templates or as inspiration. But the important thing is to keep in mind the principles above — which, for us, also shape our pedagogy, just as Stommel suggests.

Katherine’s Latin Class

For me, ungrading in introductory and intermediate Latin classes yielded a range of positive results, including high student retention throughout the sequence, low student-reported anxiety, and an interactive and positive classroom atmosphere in which students asked many questions and felt comfortable being uncertain.

I wanted to avoid the situation I have commonly experienced in which students drop the class after the first exam, feeling they cannot overcome an initial discouraging result and achieve a “good” final grade. To shift students’ focus to improving, I implemented the following structure:

- Weekly quizzes (cumulative but focusing on current topics). Students would take quizzes on Friday, receive feedback on Monday, and turn in corrections for their quiz by Wednesday. They were encouraged to work together on corrections, and some of Wednesday’s class time was spent in small groups discussing corrections.

- No regular summative assessments (no exams, no final, no nothing!).

- Regular reflections on progress and learning, focusing on identifying areas of difficulty, next steps for improvement, and needed support. I encouraged students to use their own homework and quizzes as evidence, and I have done these as often as every week.

- Self-assessment. About twice throughout the class and again at the end, I ask students to assign themselves a letter grade based on their progress rather than percent correct or incorrect. To facilitate this process, I often discussed with students different ways to conceptualize progress, focusing on how they could set and achieve specific learning goals (e.g., understand how to identify different ut clauses).

- Final portfolio. This one summative assessment, instead of asking students to do new work, asked them to compile 3–4 items that they felt illustrated their growth as Latin readers and writers throughout the class, along with a brief narrative about their strongest areas of improvement and possible avenues for continued growth.

At the end of the class, all students turned a final course grade in along with their portfolio. I have never had to lower a student’s grade. I have had to offer higher grades for students who have been unnecessarily harsh on themselves.

A key aspect of making ungrading truly equitable for students, in my experience, is sufficient scaffolding. Because they are so accustomed to traditional forms of evaluation, there is often resistance (“How will I know how I am doing?” or “I don’t know how to give a grade.”). It is therefore necessary to discuss with students very clearly what you will hope they get out of the class, offer them frequent opportunities to check in on their own progress, give plentiful feedback both on content work and metacognitive reflections, and help them set their own goals. This wealth of formative assessment, along with the lack of stress students feel when they know they are not performing for a grade, has helped refocus my Latin classes on curiosity and learning.

All this reflection and feedback, you might wonder — doesn’t it take too much time? I have found that, in actuality, the time I save by not dreaming up complex rubrics to justify grades, calculating half-points, and having painful conversations with students about their outcomes, more than makes up for the time I spend talking with my students about how they can achieve their goals.

Elizabeth’s Latin Class

For me, a system of ungrading or hybrid grading (where only some elements are given a grade) has had similar results. Students report feeling a sense of pride in their accomplishments and their ability in a Latin or Greek 101 class to go from knowing nothing at the start to being able to compose long paragraphs in the target language. They comment positively on how much feedback they get (which they also perceive as being in a supportive learning environment), and are willing to stick with the class, even as the material becomes more complex.

To get them to this place, I shifted where I put emphasis in the course to:

- Prioritizing attendance. If I can get them in the room, they will do the work, and if they do the work, they will learn what they need to know. In some ways, this is a kind of “flipped” model, but without the video content. Most of the “work” happens in the classroom, together.

- Weekly ungraded quizzes. These look like standard quizzes, but they receive no number or letter grade, though I do make copious comments. Students are shown precisely where they are strong, where they need work, and when they should come to office hours. They have been responsive in following up to meet for extra help or review challenging topics.

- Homework completion. This is not the same as homework perfection. Homework is viewed as practice, and credit is given for a sincere attempt to engage.

- Writing and Reading Comprehension. My goal is to make students better readers of Latin and Ancient Greek. While they need some grammatical scaffolding (hence the quizzes), assessments focus on their ability to read and understand. Instead of exams, students write regular original compositions that ask them to practice new forms and concepts. These are given feedback, and then students have opportunities to rewrite, or expand upon these compositions.

- Portfolio. I have, at times, used portfolios for homework and compositions, where students choose their “best” examples of their own work (based on their self-assessment), and then reflect on these submissions, explaining why they chose them and how they have led to greater learning.

- Regular check-ins. These can take numerous forms. When I am on top of my game, students have chances to reflect on their learning in midterm feedback forms or exit tickets. Yet, even in stressed out COVID times, it can help students move toward their own learning goals if we use icebreakers at the beginning of class to check not just how they are, but how they sense their own progress through the class — or, likewise, a five-minute freewrite (in English or the target language) about what they are finding easy or difficult.

- Collaborative final exam. I have started offering these as a capstone for the class. Students replicate what they do every day, working with each other on a series of tasks. Thus, final exam days are noisy and lively, full of energy and students supporting each other.

The kinds of concerns students might have with no graded tests or quizzes are alleviated, I think, by seeing the credit for homework and attendance accumulate each week, and in the rich amount of written feedback they receive. They tend to know when they submit work where their personal hurdles are, and will say, “I don’t really think I understood how to use participles,” or “I really need to practice vocabulary this week.” The structure of our activities remains pretty consistent chapter by chapter, so students quickly get a sense of pacing and workflow. Yet, more than anything, this system has been key to building a supportive, collaborative classroom. Students perceive that I care about their learning, in part because they perceive my detailed comments (and the absence of the grade) as an expression of concern for their growth.

In conclusion, we want to emphasize that not all the changes we mention above need be made at once. If you’re interested in trying ungrading but are hesitant to implement it widely, consider changing just one assessment (even as small as a quiz). Asking students to tell you about what they have learned and what they are still curious about is never a letdown.

Please feel free to contact any of us if you’d like a thought partner for building your next course!

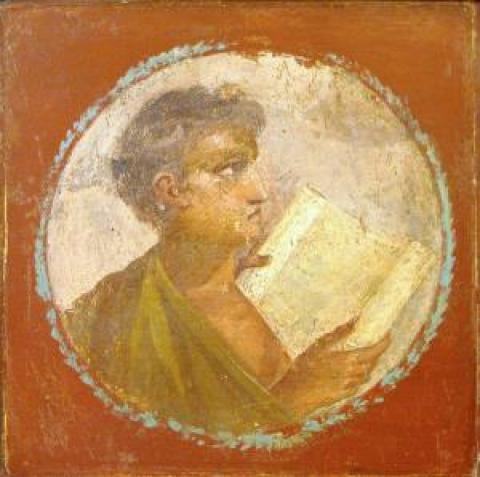

Header image: A fresco of a young man with a papyrus scroll, Herculaneum. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Authors