Ellen Bauerle and Charles Miller

August 1, 2014

Vera Lachmann was born in Berlin in 1904 into a family of the German-Jewish aristocracy. She attended a private school for girls, following which she studied philology at the Universities of Berlin and Basel and received her Ph.D. from the University of Berlin in 1931. Although she expected to teach at a German university, the bias against women led her to take the examinations that qualified her to teach at the Gymnasium level. In April 1933, with Hitler in power, she established a private school that was held on the grounds of relatives. The Nazis closed the school shortly after Kristallnacht. With the aid of friends in Germany and the United States she was able to leave Germany in November 1939. On arriving in the United States. she taught first at Vassar. Soon after, she taught for two years at Salem College in North Carolina, one academic year at Bryn Mawr, and two years at Yale. Her most substantial employment was at Brooklyn College, where she taught large courses in classical civilization and Greek drama in translation, and smaller courses in Greek: Antigone, Oedipus at Colonus, and the Iliad. Castrum Peregrini Press of Amsterdam published three books of her poetry, German and English on facing pages. A considerable number of her poems are on themes from ancient Greece. She died in 1985. In 2004 I edited Homer’s Sun Still Shines: Ancient Greece in Essays, Poems and Translations by Vera Lachmann.

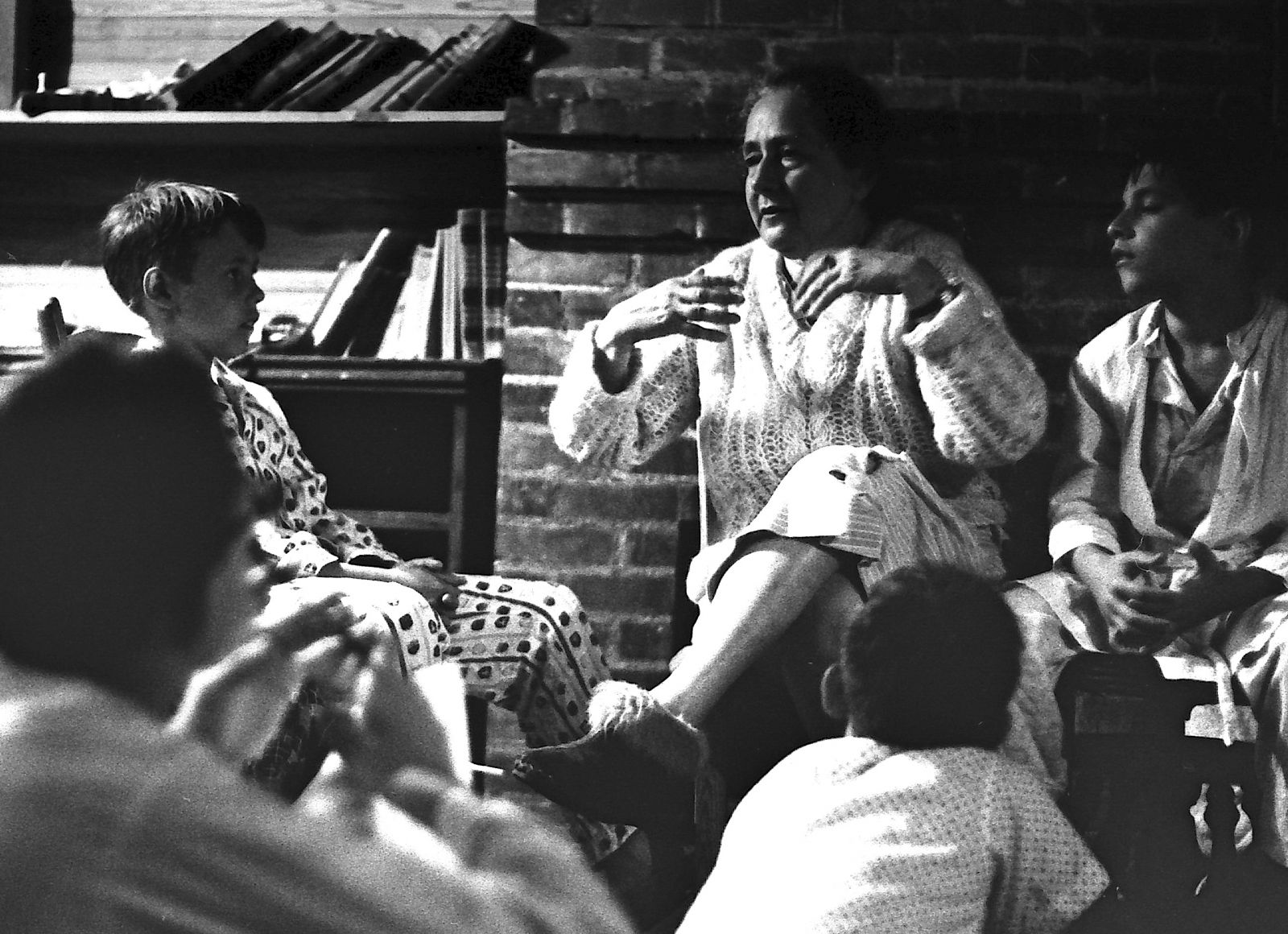

In the mid-1940s Vera Lachmann founded a camp for boys in the mountains of North Carolina, which she named Catawba. Although the boys played sports, rode horses, and swam in a spring-fed pool, Camp Catawba was distinguished by Vera’s gifts as a classicist.

Over the twenty-seven years of the camp’s operation Vera directed boys ages six to twelve in dozens of great plays, Shakespeare in the lead. Four plays, however, were by the Greeks, two tragedies and two comedies. The tragedies were The Persians by Aeschylus and Philoctetes by Sophocles (in her own translation). The comedies were The Birds and The Frogs, by Aristophanes.

For the plays she left crucial lines in the original or modified the English for the sake of her actors. The small grounds of Catawba twittered with the songs of birds: Toro-toro-toro-toro-tinx! They rumbled with the croaks of frogs: Brekekekex, co-ax, co-ax. Brekekekex, co-ax. As the chorus of Persian elders, the boys chanted a lament that, for the sake of her actors, Vera abbreviated to, “Where are our leaders . . . where?” They heard Philoctetes cry out in pain, “Papai! apappapai! papap-papap-papap-papai!”

Equally memorable was the evening story. Over the eight-week camp season, Vera told the Iliad and the Odyssey in alternating summers. First she reviewed Homer’s Greek to herself and then called the campers together. Her achievement was telling the epics. It never occurred to her to read a translation.

Once in a while she interpolated her own response into the telling. The bard Demodocus performs at a feast (Od.viii.83-95):

Once in a while she interpolated her own response into the telling. The bard Demodocus performs at a feast (Od.viii.83-95):

And then he started singing, of all subjects, about the wooden horse and the fall of Troy. Now—can you understand that?—when Odysseus heard this, that something that he had lived through, that was part of his life, had already become the subject for literature, for a song, or an entertainment among other people—that was a very strange sensation. He put his cloak over his head and quietly cried. I can understand that very well; I don’t know whether you can. Some things I have lived through have already become subjects for drama or for history or for a movie. And I can’t really stand hearing it. And it moves me strangely. And that was the way Odysseus felt. He just cried.

She told the boys about the winds of Poseidon (Od.v.291-96):

Now some of you seemed to be interested in that morsel of Greek that I gave you. So I copied out a few more lines. It’s that place, if you remember, when Poseidon comes back from Africa and says, “Now see what we have here: my enemy is almost out of danger.” And as you may remember, there was a terrific storm that he raised, with all the winds going against each other. If you just take it in like music it will show you about the winds being so wild. First I translate it: “Having said this, he (that means Poseidon) drew together the clouds. And he stirred up the sea in his hands, having the trident. And he raised all the whirlwinds, all sorts of winds. And he hid the sky and the earth at the same time, with clouds, and the sea. And night fell down from the sky. And there was the East Wind and the West Wind, and they fell upon the South Wind—that is a dreadful one—and the North Wind, that creates horror. And they stirred up tremendous waves.” Now let me say it in Greek, as if it were music.

What did the parents of boys learn about Vera, the plays, the dramatists, and Homer? Every week she wrote to tell them. Here are excerpts from letters ranging from 1952 to 1970:

You should have seen the circle of little imps around the tall flame of the campfire, sticking their marshmallow sticks into the fire and listening to the fate of poor Prince Telemachus. The Persians is quite a bold experiment, and would be, even for any grown-up group of amateurs: an archaic Greek tragedy, in a somewhat clumsy, heavy-worded eighteenth century translation. The chorus has twelve members, as was usual in Athens, the entire cast numbers twenty-one, so the majority of the campers participate and the rest will help with costumes, props, makeup, and lights. For the actors, the task is to memorize 3-5 pages of heavy verse. Yet believe me—it’s coming! The dignity of the play, the pathos of a queen mother trembling for her son, a messenger who brings the eyewitness report from the greatest minority victory in antiquity, the ghost of the former king advising the living to enjoy the present day, and a defeated king coming home in rags and frantic with despair—all that begins to take on shape in our rehearsal. We know that putting on The Persians means inviting our youngsters to the heights of art instead of playing down to them and their usual range of superman, television, and comic strips.

I admit it is rather daring to infect a six- to twelve-year-old group with Aristophanes, but the Old Athenian can be proud of his 2400-year-old jokes which still work and make people—even very young people—chuckle at every rehearsal.

In the evening story I have reached the tragic turning point of the Iliad. Achilles has decided not to go back into battle, but does not know yet that that will cost him dearer than his life, that his best friend has to die for him.

We gave permission to the campers to quote the very daring Aristophanes lines [from The Frogs] if they properly say “quote” and “unquote.” We had another full reading rehearsal which impressed an accidental guest, a Harvard graduate classics student, beyond words. Odysseus has by now come to his home as a beggar.

I had them all together at bedtime in the front room of the Citadel and told them about Mother Earth giving Delphi to Apollo as a birthday present. As I have been to Delphi recently the story had a vivid meaning to myself and, it seemed, also to the boys.

Vera Lachmann was also a poet. She wrote only in German. The literal translations may obliterate some of the beauty of the original, but one can still understand the scene and feel the passion. Here she is, sitting in a field at Catawba reading Pindar. (The poem was published in 1982 in Grass Diamonds, the third of her three bilingual volumes of poetry.)

Epiphany

Yesterday I met God. And I am still shaken.

I sat in the summer meadow where it most silverly trembles.

Nourishing odor of herbs arose from the warmed soil.

My book lay open, Pindar’s Olympic Odes.

A pair of butterflies of dotted brown silk pursued each other—

their flight zig-zag—and plunged into the sea of grass. A bird

steadily repeated its decorously ornamental phrase. Leaves

fluttered on high in the midst of blue ecstasy.

A black speck of dust blew onto the open page between Pindar’s

mighty lines. I started to wipe it away. No dust! A tiny insect. It

ran, wanted to live, did live.

Then the bug became God. And my soul shivered.

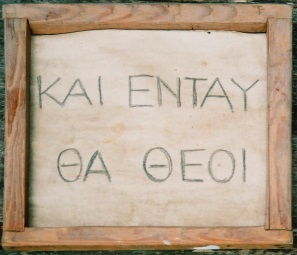

What about the counselors at Catawba? Few at the camp were classicists, but one of them assisted Vera in translating Philoctetes. Another learned enough Latin from her to enter a graduate program in English and comparative literature. In a reverie that he later wrote describing his experience, one sentence, repeated several times, stands out: “A Hellenist she said she was, not really a Latinist.” A third counselor, with no particular interest in the classics, was a lanky Eagle Scout who played the role of the Trojan horse at a campfire skit. A fourth was an American who had learned Greek from Vera in Germany and helped her escape. It was she who in the mid-1940s wrote out a line from Heraclitus (by way of Aristotle) with a crayon and constructed a frame for it: ΚΑΙ ΕΝΤΑΥΘΑ ΘΕΟΙ—HERE ALSO ARE GODS. The sign, which Vera seldom explained (was Catawba a divinely inhabited place?), was displayed in the camp’s small office until her death.

A former camper who spoke at her memorial celebration brings our narrative to its close. “For those of us who began young at Catawba, whose life . . . before Telemachus and Athena, whose life before Catawba is hard to recall, for those of us who were with Vera at camp over many summers—we can no more forget her than we can forget ourselves. She is like the hydrangea bushes on the slope next to the Mainhouse: so many blossoms; so long enduring.”