Amy Coker

November 7, 2022

Aristophanes’ Ecclesiazusae or Assemblywomen is not a popular play. Frequently derided as a disappointing work, this satire on political power has been the poor relation of the much-studied, much-performed other of Aristophanes’ “women’s plays,” Lysistrata, the famous comedy about the sex strike. Even looking along the shelves of the wonderful ICS Library in London, the cupboard is almost bare.

One reason for this is a structure unfamiliar when compared to plays from some decades earlier. Little or no part is played by the chorus, and the heroine of the first half, Praxagora — who successfully contrives to get a bunch of women into the assembly, where they vote for a range of radical reforms — vanishes about halfway through. The second half of the play is basically a series of slanging matches between some nameless women and a hapless young man who is their collective boytoy. Additionally, the humor of this play comes primarily not from clever and witty pastiches of literary or theatrical culture, but from a kind of knockabout farce more familiar in Roman comedy and in mime — and from a considerable amount of sexual innuendo, below-the-belt humour, and the ancient equivalent of four-letter words. Even Jeffrey Henderson, author of the famously not-shy Maculate Muse, has little positive to say about the play: according to him, it has a certain “unique ugliness.”

Classics as a discipline has increasingly looked towards popular culture and everyday language over recent decades, and to an ancient world that is not just the playground of the elite. But this approach has not yet reached the sweary women of Aristophanes. Part of this is the ambivalent relationship of Classicists — and people in general — with bad language. Everyone, even the most linguistically prurient, knows what it is: think of the famous 1964 dictat of American Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart in Jacobellis v. Ohio on the definition of hardcore pornography, “I know it when I see it.” A word acquires and maintains offensive qualities only when it is considered to do so by the speech community within which is it used. This is offense by consensus. These are words which we all know we shouldn’t say, and yet sometimes do. Even within stereotypically stuffy old Classics, when the Cambridge Greek Lexicon appeared in 2021, it was its casual use of fuck and four-letter friends that made the headlines, not just the sheer enormity and newness of the epic scholarly enterprise. Despite this fondness for the forbidden, many wish to avoid being seen using such words in their own speech patterns, for fear of being labelled impolite or crude, with a potential for loss of social standing. My grandma would still tell me that swearing is “common.”

This comes into sharper relief when we look at female language. Women do speak differently from men, both now and in the past. For example, English women tend to use more tag questions than men (“I definitely do, don’t I?”), and, going by Aristophanes, the oaths — in the sense of exclamations, OMG! — of women and men in the fifth-century polis were different (By Artemis, they really were!). When it comes to impoliteness and offensive language, social restrictions are still stronger for women than they are for men: nice girls don’t swear, and female speech is positioned — by women, but in accordance with prevailing social norms — as subordinated to the male.

Swearing is seen as assertive for men but aggressive for women. It is not that women don’t know offensive terms, but rather that they operate in social networks that restrict their use, or those that are not reflected in the dominant discourse. And, for Classical Athens, it is primarily the dominant, male discourse which is preserved.

I would not characterize my younger self as particularly feminist. But coming into my fourth decade in the #metoo era, my experience of life has definitely made me more willing to call out everyday sexism, unequal pay and career opportunities, and the casual nonsense that my sex still has to put up with on an alarmingly regular basis. One aspect of this is verbal inequalities (e.g., “women drivers,” or the expectation that Dr. Coker is a man). So, when it comes to the “outspoken” women of Aristophanes’ Assemblywomen, with whom I find myself identifying more and more, I’d like to suggest they should not just be dismissed as a vehicle for crass and disappointing jokes, but rather can be read more positively, perhaps even reflecting a glimpse of the realia of ancient Athenian women and their verbal behaviors, in what is, in fact, a very funny play. After all, Aristophanes’ plays come close-ish to passing the Bechdel test for their interactions between female characters — which is more than some recent movie blockbusters do.

What follows focuses on one of the most outspoken women of Assemblywomen, Old Woman A. This otherwise unnamed character appears at 877 and delivers her last line at 1044, towards the end of the play. The action of this whole portion of the work is centered on a selection of women competing to get a young man named Epigenes into bed, thus enacting one of the new rules the women have voted into law in the first phase of the play. Epigenes is keen on the Girl (Κόρη), but Old Woman A, and later Old Women B and C, assert their rights under this new legislation to have sex with him first.

First of all, let’s be careful not to overdo the talk of hags and crones. Yes, there is certainly a vein of ancient invective directed against nasty, saggy-breasted, sex-mad, bibulous old women as stock characters, and there are plenty examples of this in the mouths of characters within this scene. The Girl, at 884 and 926, uses ὦ σαπρά “rotten”/“putrid,” as does Epigenes at 1098, and she also uses γρᾷδιον at 949, 1000, and 1003, plus μαῖα, “granny/nurse-y,” with implications of servility, at 915. But the character in the play is labelled simply as Old Woman A (Γραῦς Α᾽). Let’s not buy into this “hag” rhetoric when talking about the speech habits, mocked or not, of this character.

Old Woman A is linguistically dextrous, riffing on well-known popular songs at least twice, engaging in a sustained back-and-forth with Epigenes, and not just echoing a well-known tune he sings but also deploying a clever segmentation joke with a filthy word (διασποδῆσαι ~ νὴ Δία σποδήσεις “by Zeus, you’ll pound away,” 938–941 = 942–945). As part of making her case, she restates the new sex law (1015–1020) with its comic legalese προκρούω, “pre-bang.” At line 920, she also wheels out an allusion to what is likely the most offensive Greek verb given its usage pattern: λαικάζω (glossed by the Cambridge Greek Lexicon as “suck cocks”). English has the “f-word,” but Greek had the “lambda-word,” and this is how Old Woman A refers to it. In sum, she gives as good as she gets.

Solid interpretation of some of this banter is still wanting, but a high point of Old Woman A’s frank sexual references and use of offensive (or dysphemistic) terms — it is important to keep these two separate — comes soon after she arrives on stage and gets into what is best described as a singing-contest-cum-rap-battle with the Girl. Note that the whole of this is prefaced in typical Aristophanic style by a metatheatrical comment from the Girl at 888–889, revealing that all the players, and indeed the audience, are well aware of the perceived crudity of what’s to follow. In the second of a pair of stanzas, echoing the Girl, Old Woman A comes out with (906–908):

ἐκπέσοι σου τὸ τρῆμα

τό τ᾽ ἐπίκλιντρον ἀποβάλοιο

βουλομένη σποδεῖσθαι.May your hole fall out

and may you lose your “sit on”

when you want to get pounded

This is surely not a pair of references to particular failings of the Girl’s anatomy, even if Sommerstein seems desperate to see some variety of female prolapse in line 906. Rather, they are more general wishes for her not be able to get laid. Compare here the kinds of negative wishes occasionally seen in surviving curse tablets (defixiones), combined with the semantic bleaching in the curse (negative wish) “go to the crows” (βάλλ᾽ ἐς κόρακας).

Old Woman A then deploys the verb σποδέω (spodeō), “pound.” Observe the passive voice: “get pounded.” Aristophanes’ women always speak of sex in passive terms. They don’t want to have sex, but rather be fucked. It is essentially impossible to know whether this was the case in women’s own private conversations, given the paucity of evidence, and whether this was the way women spoke about sex, or just the way men talked about women talking about sex. In contrast, if they want to, English-speaking women can now can certainly talk of actively shagging someone. The fact that this is all sung — and to a familiar tune — surely adds to the humor: think of Weird Al Yankovic or, for the UK market, some of the more famous songs of the Amateur Transplants, a 2000s-era musical comedy act who parody well-known tunes, with added swearing.

Old Woman A speaks with remarkable freedom of expression, often seen as enabled by her age and her possible status as a widow or a woman beyond child-bearing age. Old Woman A is also described as a sexual aggressor through her language, and one of the “predatory hags” of the play. Maybe being older, she’s just unafraid to talk about wanting a good fuck, even though she still can’t use the active voice to state it? Maybe she’s just sick of the bullshit which has dominated much of her life, as well as a prevailing discourse telling her she is not allowed to want sex for its pleasurable merits? To want sex for enjoyment — then and often now — labels a woman as a slut.

Old Woman A’s breaking of the “proper woman” stereotype can be viewed as subversive in the same way as words like cunt and pussy have been reclaimed by some feminist thinkers, or the deliberate verbal provocation of punk. It’s conceivable that this is how at least some of the ancient audience viewed her, too. Like Old Woman A, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve certainly gotten angrier about the subtle expectations of behavior, verbal or otherwise, that are placed upon me. Maybe older women are always more strident than their younger selves, more frank in their criticisms and manner of expression. There’s something defiant, triumphant, and inspiring about Old Woman A.

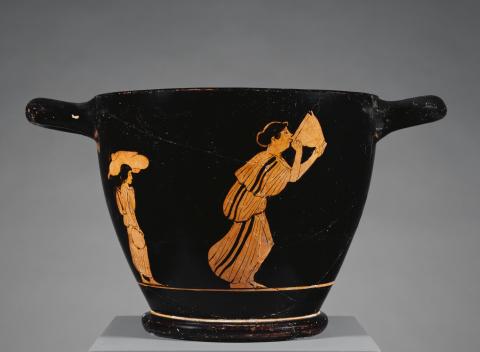

Header Image: A group of Tanagra figurines in the museum at Corinth (2018). Image courtesy of the author.

Authors