Ayelet Haimson Lushkov

January 5, 2022

What do you read for an insurrection? Classics offers plenty of material for revolutionary bibliophiles: compilations for the budding revolutionary, handbooks for coups both successful and failed. The Capitol rioters certainly had their Classics before their eyes, as Curtis Dozier outlined shortly after the event: Caesar and Xenophon, Vergil and Herodotus.

But in January 2021, I was reading Sallust—and an apt choice it was, too. Not because of what Sallust writes — Catiline’s attempt to overthrow the government or Marius’ attempt to change Roman institutions — but because of what he passes over. He was there at the swelling of the atmosphere that led to the burning of the Senate house on January 19th (what is it about Januaries?), 52 bce, during the funeral of Publius Clodius.

The turbulence of 52 bce found its way to the floor of the U.S. Senate on the same day as the insurrection, in a speech by Sen. Michael Bennet (D–Colorado), as good an example as any for how to read the two insurrections together:

And I was thinking about that history today as we saw the mob riot in Washington, D.C., thinking about…what happened to the Roman Republic when armed gangs — doing the work for politicians — prevented Rome from casting their ballots for consuls, for praetors, for senators. These were the offices in Rome, and these armed gangs ran through the streets of Rome, keeping elections from being started, keeping elections from ever being called. And in the end, because of that, the Roman Republic fell and a dictator took its place.

Sallust, a pessimistic historian at the best of times, might well have sympathized with Bennet’s apprehension. Catiline, too, was driven to his conspiracy by a failure to win public office in an election, and his naked ambition shaped the generation that grew up to follow Clodius. Electoral defeat bred wounded entitlement; entitlement bred a failed coup; and the failed coup bred violence and electoral disruption. A vicious cycle of political pessimism that draws clear parallels between then and now, and which we might do well to learn from.

Asconius and Cicero between them give us enough of a sense of what kind of feelings were running, and how high, on the days just prior to the Senate burning. On the day before the riot, January 18th, Sallust was one of two tribunes holding informal rallies (contiones): Cicero called it deranged (insanissima, at Pro Milone 45); Asconius plumped for seditious (seditiosior, at Pro Milone 43) and labeled the tribunes “turbulent enough” (satis inquieti, ibid.). Sallust pops up on the days following the riot as well, but we do not know how pro-Clodian he really was, and he is unaccounted for in the funeral-turned-riot-turned-Senate-burning itself.

Even so, I have found it difficult not to imagine him, a fiery tribune of the plebs, on the Capitol steps on January 6th. What would he have been doing? He would certainly have understood the atmosphere, with its inflated emotions, rampant propaganda, and widening polarization. What would he have made of the events before and after? Of the planning text-threads among legislators, only now coming to light, or the heroism of Officer Eugene Goodman, or the gibbet prepared for Vice President Mike Pence, and the congresspeople fleeing the building to safety?

There would no doubt have been no shortage of material for a monograph for the aged Sallust — but what would the young Sallust have been doing on the actual day? Would he participate, watch from the sidelines, heckle? We cannot know, but somehow January 6th makes it impossible not to see the political involvement of ancient historians in a new, and more immediately participatory, light.

Did Sallust light the fire that torched the senate house? Unlikely. But he was there in the city, hearing and experiencing this event in real time. I imagine him knowing that he was, only the day before, a part of that groundswell, and wonder what effect it had on his views. I imagine him heckling Cicero and wonder how much of the last generation of the Roman republic was a product of the accumulated traumas of instability.

I wonder how a young man watching the heart of government violated grew to overcome “arrogance and graft and greed” to write history in his old age, and whether American democracy has long enough to find out.

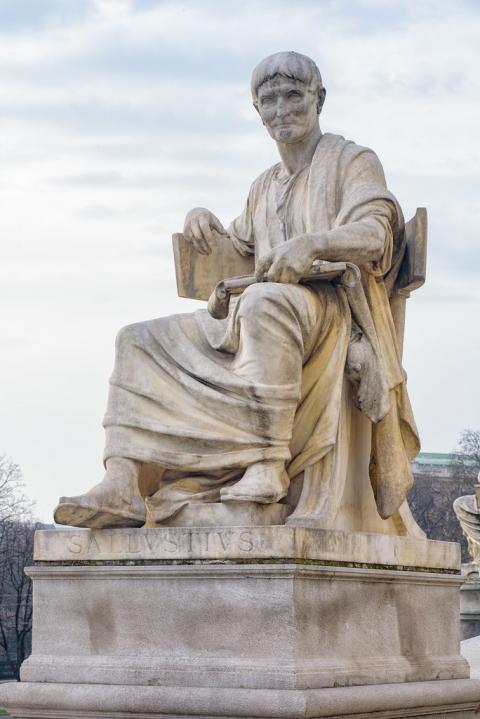

Header image: Statue of a seated Sallust. Image courtesy of Creative Commons.

Authors