Claire Catenaccio

November 15, 2019

Today we wish to introduce a new project: Women in Classics: Conversations. This venture consists of a series of interviews with female professors of Classics, many of whom were the first hired or the first to receive tenure at their institutions in the 1970’s and 1980’s. These academic women blazed a new trail as teachers and scholars at a time when university positions in many fields were overwhelmingly held by men. They did so in a discipline that has been described as “one of the most conservative, hierarchical, and patriarchal of academic fields.” Their experiences, as presented in these interviews, provide colorful, candid snapshots of a critical moment in the history of the discipline.

Beyond providing depth to the written history of our field, there is much we can learn from these stories about how to address the issues of diversity, inclusion, and relevance that Classics faces today. Recent newspaper articles have documented how public websites such as Wikipedia lack coverage of notable women in academia, and the recent work of the WCC-UK to hold Wiki-sprints for adding women in Classics has attempted to address this gender bias. College and university websites rarely provide information about the history of female scholars in individual institutions and departments. Although the history of women in mathematics and the sciences has received significant attention in recent years, this issue remains understudied in the domain of Classics.

Yet women have shaped the field in important ways in America, despite educational structures designed to exclude them. In the nineteenth century, American colleges gave women early access to a Classical education. As Barbara McManus writes:

On the one hand, [women in America] faced the same elitist and exclusionary masculine tradition as their counterparts in England and on the Continent; on the other hand, they had educational and professional opportunities unavailable to women in other countries. American colleges offered women a classical education earlier in the century and on a more broadly accessible basis than anywhere else in the world. Furthermore, educated American women had respectable ways to use their education beyond the amateur role of the “women of letters.” Many taught Latin on the secondary level, and the network of women’s colleges in America offered at least some white women the chance for a professional academic career in classics. (Classics and Feminism, 27)

.png)

Figure 1: Helen Magill White, a Classicist, was the first woman to earn a Ph.D. in the United States (Image is in the Public Domain via Wikimedia).

Since the founding of Harvard College in 1636 as the first institution of higher learning in North America, a small number of exceptional women have found places in American Classics departments. The admission of women as both students and faculty members began slowly in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Helen Magill White (1853-1944), the first woman to complete a doctorate in any subject in the United States, earned her Ph.D. in Classics from Boston University in 1877, with a dissertation on Greek drama. Abby Leach (1855-1918), a professor of Greek and Latin at Vassar College, in 1899 became the first female president of the American Philological Association (prior to its name change to the SCS). Grace Harriet Macurdy (1866-1946) served as a professor of Greek at Vassar College for forty years and was arguably the first woman to achieve international recognition as a professional Classicist.

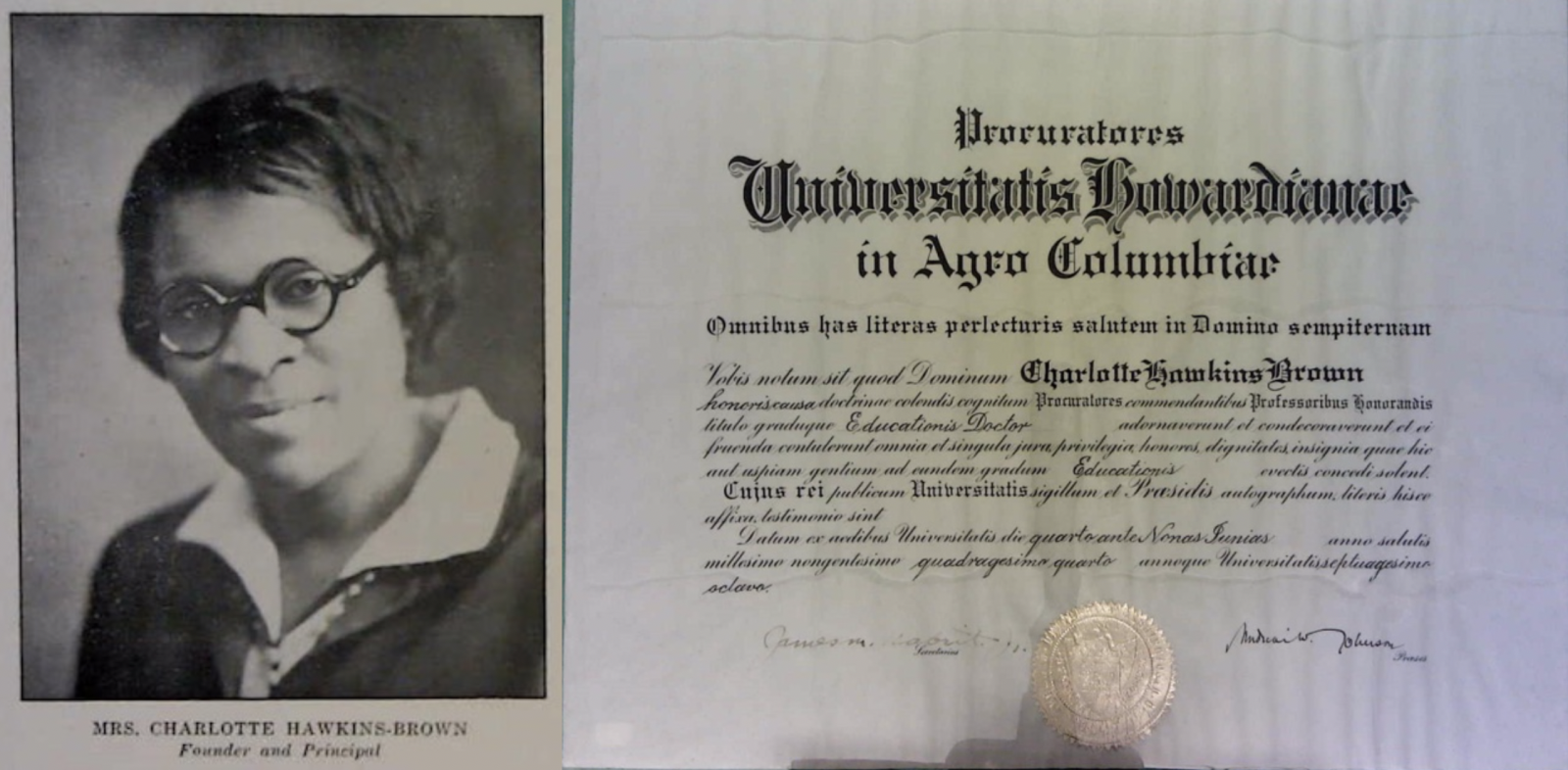

The history of women in the field of Classics is also rich in the contributions of classicists of color. Black Classicists such as Anna Julia Cooper (c.1858–1964) and Charlotte Hawkins Brown (1883–1961) taught both Greek and Latin at the university level at a time when African-Americans were prohibited from almost all opportunities in higher education. Many of these women benefitted from the existence of prestigious women’s liberal arts colleges in the northeastern United States.

Figure 2.1-2.2: (Left) A photographic portrait of Charlotte Hawkins Brown (Image via the Schlesinger Library of the Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University via Flickr); (Right) Brown’s Ed.D. honoris causa diploma (note dominum and other masculine forms in the text: the template used for the diploma assumed the honoree to be a man) (Image via Wikimedia).

The integration of women into male-dominated, elite research universities such as Harvard, Princeton, and Yale, was a slower and more fraught process than within the small liberal arts colleges. Astonishing as it may seem today, many of the Ivy League schools accepted only male undergraduates until around 1970. During the previous decades, larger social, economic, and technological forces led unprecedented numbers of women to attend college and graduate school in America. Simultaneously, the feminist movements of the time gave voice to an increased awareness of inequalities in education and opportunity.

Within Classics, women rightfully demanded to be taken seriously as scholars and as academics. As shown in the figure at the end of this article, many degree-granting institutions in the United States hired their first female professors of Classics at this time. The number of women in Classics has continued to rise in the intervening decades, as the rate of change of women’s roles has accelerated over the course of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Despite great strides, women are still markedly underrepresented at the highest levels of the field. They made up only 32% of tenured full professors in American university departments at the time of the last published survey by the Society for Classical Studies, in 2014. In the afterword to the recent collection on Women Classical Scholars, Rosie Wyles calls for further studies into individual women and their experiences:

As women become more visible as scholars and teachers, have they been assimilated into a male-centric paradigm, or have they been successful in revising it? How does this greater visibility and engagement relate to broader social trends of female empowerment and widening public access to Classics?

The interviews contained in Women in Classics: Conversations are my attempt to find out the answers to these questions, and to pursue a fuller understanding of the directions that the discipline of Classics has taken in the United States over the last sixty years. By publishing these interviews as a series of blog posts, I am responding to a call for more public intellectual work that is easily accessible to non-specialists over the internet (as voiced, for instance, by Eric Adler).

The idea of a collection of interviews arose out of my own academic work on Greek drama and out of my extracurricular experience as a director, dramaturge, translator, and actress. My love of drama as a living art form suggested to me the value of the interview format, where different voices share the stage. Of course, I impose a degree of narrative on the material in my selection and in the way in which I guide conversations with my subjects. However, I hope I leave these women room to speak for themselves.

.png)

Figure 3: Theater scene from the Villa del Cicerone, Pompeii, now at the Naples Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy (Image via Wikimedia).

These posts are limited in their geographic scope to the United States, since the acceptance of women in the field has taken a unique trajectory in this country. I focus on women who work at co-educational, degree-granting institutions, although I have also spoken to those employed in other educational environments. The women interviewed are remarkable for their intelligence, humor, and candor. They speak openly about their education, their teachers and mentors, their first jobs, their tenure cases, and about overcoming misogyny, racism, and structural barriers in academia. These interviews will appeal to young scholars, like myself, who do not always appreciate what was accomplished by earlier generations; to members of those earlier generations, who perhaps may learn things that have been hidden in plain view; and to all those interested in the history of women in higher education in this country. Although each woman’s story is different, they share an optimism about the value of the field that is heartening, especially since the future of the humanities today is so often called into question. These women believe in the value of Classics. I look forward to sharing their stories with you in upcoming posts over the next few months on the SCS Blog.

.png)

Figure 4: A timeline of the tenure dates of female Classics professors in American colleges and university departments (data collection is ongoing; compiled and kindly made available by Tori Lee).

Further Reading:

Eric Adler, Classics, the Culture Wars, and Beyond (2016)

William M. Calder and Judith P. Hallett, “Six North American Women Classicists” (1996)

Barbara McManus, Classics and Feminism: Gendering the Classics (1997)

Michelle Ronnick, Twelve Black Classicists (2014)

Header: Three Mycenaean terracotta female figures, 1400-1300 BCE, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY (CC0).

Authors