Giacomo Loi

October 22, 2021

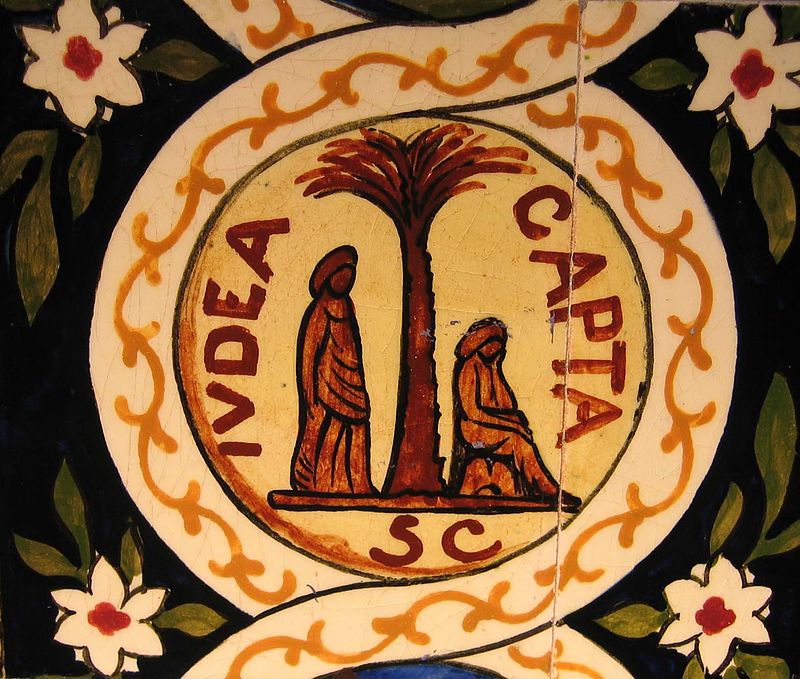

As I strolled one day in the old center of Tel Aviv, I entered the house of Haim Nachman Bialik, the Hebrew national poet. An imposing building, it constitutes a manifesto of Jewish art in the early 20th century: the architectural style reprises oriental shapes, alternating arches and square forms; the decoration aims to express a quintessentially Jewish art. As I daydreamed about the poet holding private meetings and public receptions with the foremost representatives of culture and politics of his day, my eye was caught by two decorative tiles. These tiles, located at opposite ends of an arch that leads into the salon, represent two opposite moments of Jewish history: on one hand, a tile reproduces the Judaea capta coin minted by Vespasian after the First Jewish War; on the other, another tile mirrors Vespasian’s coin, proclaiming, in Hebrew letters, “Judaea liberated.”

The contrast between the two moments, marked by the different alphabets, the Latin and the Hebrew, is striking: the reproduction of the Roman coin seems oddly out of place in a house decorated only with Jewish motifs. While the two tiles provide, from a nationalist perspective, a sense of closure to Jewish history, they also mark the irreversible change that Jewish culture underwent in the classical world. Moreover, the ancient encounter between the Greek and the Jews is enshrined in the festival of Hannukah; that with the Romans is memorialized in Tisha BeAv, the memory of the destruction of the Temple, and in a way also in Lag BaOmer, which alludes to Bar Kochba’s revolt against the Romans.

As I contemplated the tiles in the Tel Avivian sanctuary of Hebrew culture, I could not but wonder: what is the place of classical culture in Modern Hebrew culture?

Figure 1: Beit Bialik, the house of Haim Nachman Bialik © Ori Lubin

Figure 2: The Iudea Capta tile in Beit Bialik’s hall © Talmoryair

My dissertation, “Our Quarrel Is of Old”: Classical Reception in Modern Hebrew Literature, answers this question. The title is a quote from Shaul Tchernichowsky’s poem In Front of the Statue of Apollo (1899), in which the poet meets the pagan god of youth, beauty, and poetry, and expresses his longing for such a god, since the god of his forefathers has been bound by his own faithful — an image in tune with Jewish cultural renovation at the turn of the 20th century. In a way, Apollo works like a mirror not only for the god that the poet desires, but for the new Jewish identity he strives for: a youthful, flourishing, muscular and masculine New Jew, able to embrace Western culture and, at the same time, to forcefully oppose antisemitic violence.

As Tchernichowsky bridged the distance between the classical world and Jewish culture, writing classicizing poems like this one, together with translations of Homer, Horace, and Anacreon, historical plays, and essays, he came to be known as the “classical poet” of Hebrew literature, the poet in whom the impact of the classical tradition in Hebrew culture reached its zenith. However, in my view, Tchernichowsky does not represent the culminating point of this story; rather, he begins a story of classical reception in Modern Hebrew literature and culture, one that still needs to be told.

Figures 3 and 4: Two landmarks in the investigation of classical reception in Hebrew: Yaakov Shavit’s Athens in Jerusalem (1997) and Nurit Yaari’s Between Jerusalem and Athens (2018)

In his Athens in Jerusalem (1997), Yaakov Shavit, a scholar of Jewish intellectual history, examines the influences, mediated and not, of Greek culture onto modern Jewish culture, affirming that the influence of classical culture had been fundamental in the creation of a Jewish secular modernity. Nurit Yaari’s 2018 Between Jerusalem and Athens, meanwhile, explores the central role that classical Athenian drama played in the development of an Israeli local theatrical tradition. Yet one important thing is missing from their accounts: Rome.

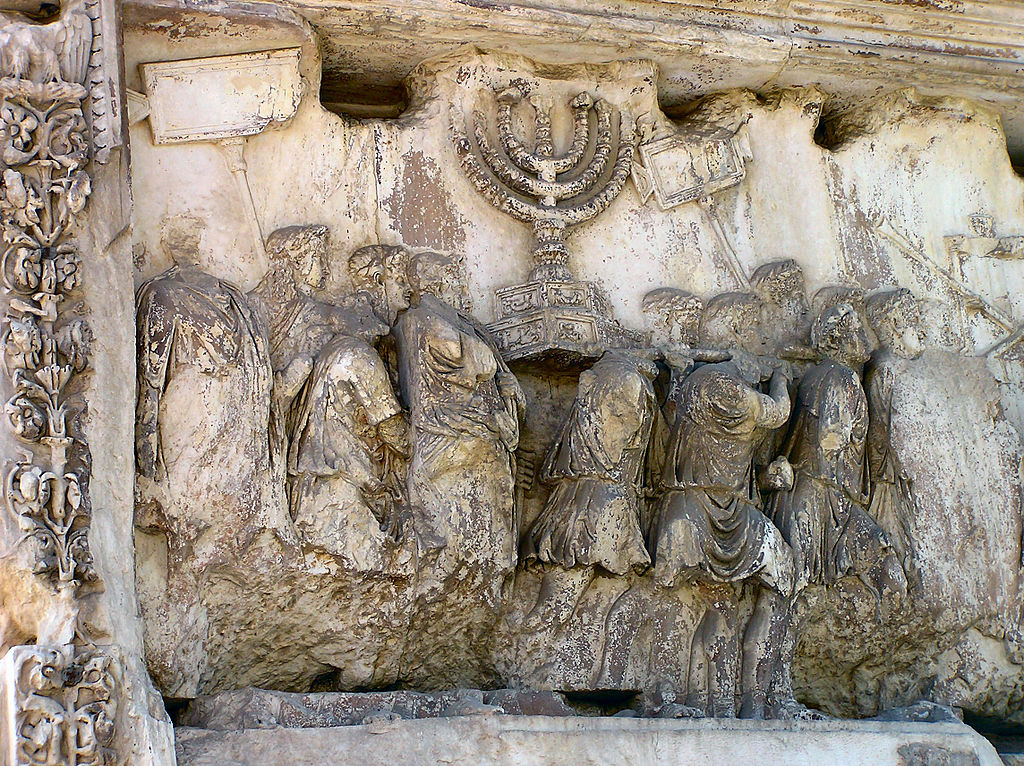

Figure 5: From the Arch of Titus in Rome: the menorah of the Jerusalem Temple is brought to Rome after Roman victory in the First Jewish War (also known as the Great Revolt, 66–73 CE)

Can one tell the history of classical tradition without Rome and Latin culture?

The reason for such a choice is apparent in the titles of Shavit’s and Yaari’s books: they both play on Tertullian’s famous question Quid ergo Athenis et Hierosolymis?, a question that returned throughout the centuries, in various forms — for example, Matthew Arnold’s Hebraism and Hellenism. This time-honored formulation shaped the question of classical reception into Hebrew culture, reducing “classical” to merely “Greek.” One could also ask the question “what has Rome to do with Jerusalem?,” following Moses Hess’ book Rom und Jerusalem (1862). This question too, however, would offer a limited, one-sided view of classical reception in Hebrew culture.

I have chosen to examine side by side the two cultures of classical antiquity and their influences on Modern Hebrew literature because, I argue, the different relationships of ancient Jewish culture with Greek culture and with Roman culture respectively shaped the modern Hebrew reception of these two cultures in different ways, with each classical culture providing different aesthetical and ideological repertoires to Hebrew writers who turn to it through translations or the mediation of Western literatures and arts.

Sitting in Bialik’s house, my eyes were not only attracted by the Roman-inspired tile. Through the windows, I could see the old Bauhaus-style city hall of Tel Aviv, just across the square. I could feel the crossroads at which Jewish culture found itself at the beginning of the 20th century, between its Diasporic past and a Mediterranean land, between a religious tradition and a nationalist ethos, between East and West. As I said, the Graeco-Roman world played a role in the creation of a new Jewish identity. Rome figures as the symbolic opposite of Jewish political autonomy; the Hellenic god of Tchernichowsky offers a model for the new Jewish man.

Within Jewish culture, too, there were different worlds that developed in different directions. Tel Aviv, the first secular, Hebrew-language city, provided a counterpart to the old Jerusalem, the city of traditional Judaism. Therefore, an investigation of classical reception in Modern Hebrew culture has to be “a tale of four cities,” to play with Dickens’s famous title. My dissertation explores the links, the complementarity, but also the oppositions between the two cities of the classical past, Athens and Rome, and the two cities of Hebrew modernity, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. Each city, as a symbol for distinctly different cultures, can be read in opposition to the other. Hebrew writers often bridged these oppositions, opening new ways to think forward.

My study offers a history of Modern Hebrew literature from the mid-19th century to the 2010s through classical reception, illustrating the different repertoires that Greek and Roman antiquity provide to Hebrew writers. Rome, for example, invites thoughts about decadence, death, and the question of the afterlife, whether through its archaeological ruins in Israel, as it is the case in Dan Pagis’ poem “Decline of an empire,” or through Cicero’s reflections in De re publica VI, as we find in Yaakov Shabtai’s 1977 epoch-making novel Past Continuous. Greece, for its part, inspired a revolt against tradition, as Tchernichowsky demonstrates, but also models of anti-heroism: in a radio drama by Meir Wieseltier, Philoctetes becomes a voice of dissent against the First Lebanon War and the beguiling emptiness of Israeli war propaganda; Haim Gouri’s “Odysseus” represents the disillusionment of the soldier who comes home from the war. While these anti-heroes oppose the models of heroism offered by state propaganda and offer a different, critical view on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, other characters of myth allow a feminist intervention—as does Nurit Zarchi’s Eurydice, who refuses to go back to life, giving voice to her trauma as a sexual assault victim—or develop an insightful take on the intraethnic rift between Ashkenazi and Sephardi-Mizrachi Jews, as A. B. Yehoshua’s 2011 novel The Retrospective does.

Figures 6 and 7: Two stills from my (Zoom) conversation with A. B. Yehoshua on the reception of classical myth in his novels. From the movie The Last Chapter of A. B. Yehoshua by Yair Qedar, Israel 2021 © Yair Qedar and Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation (Kan 11)

The boundaries of Modern Hebrew literature embrace not only the national culture of Israel, allowing exploration of political issues, propaganda, and internal dissent, but also the voice of minorities in Israeli society. At the same time, Modern Hebrew literature is an open window on global Jewish culture and its relationship with Europe, the West, and the Diaspora. Jewish and non-Jewish comparanda from other national literatures help better contextualize Hebrew texts in their Israeli milieu. Moreover, by comparing these texts, one can draw the first lines of a history of Jewish classical reception, a much longer and geographically broader story.

The case study that best exemplifies the double, Jewish and Israeli level and Hebrew classical reception’s points of contact with the classical world, both archaeological and literary, is the short story “The Times My Father Died” by Yehuda Amichai (1924–2000). The story is Amichai’s autobiographical attempt to come to terms with his father’s death. As the title suggests, the narrator’s father dies, metaphorically, many times throughout the story. He dies during the liturgy of Yom Kippur; he dies during his years as a soldier in the trenches of World War I; he dies when the Nazi persecution forces him to flee Germany for Mandatory Palestine. When his father really dies, the son continues to see him in his dreams.

In the final scene, the son meets the father in a surreal setting: “Once I was walking along the Via Appia in Rome. I was carrying my father on my shoulders. Suddenly his head sagged down and I was afraid he was going to die. I laid him down at the side of the road…I saw him through the ancient Arch of San Sebastian.…But I didn’t know if he was still alive. I turned round again and saw him, a very distant object, through the ancient arches of San Sebastian’s Gate” (transl. Schachter). The Appia, a place twice consecrated to death — as a cemetery of a dead civilization — becomes an imaginary Underworld.

Figure 8: Mausoleo del Casal Rotonda - Via Appiah Antica - the Appian Way. Image courtesy of Creative Commons.

Amichai engages with antiquity both through a Roman archaeological site and through the literary and iconographical tradition of the Aeneas myth. The son carries his father on his shoulders, just as Aeneas carries Anchises out of burning Troy; after he dies, he sees him in his dreams, just as Aeneas does; just like Aeneas, he is ready to go down to the Underworld to see him once again.

Amichai goes beyond the boundaries of Jewish culture: since Jewish myth does not provide the possibility of a legitimate journey to the Underworld, the writer turns to a classical myth of katabasis. When the feeble father is compared to Anchises, we feel his sorrow at leaving the country of his birth. Meanwhile, as Amichai transfigures himself into Aeneas, he portrays himself as the refugee hero ready to found a new community for his people, an image of the secular “New Jew.” His burning Troy is Germany, enflamed by Nazi antisemitism and soon to be devastated by World War II. In the long shadow of Aeneas, Amichai magisterially brings together his own trauma of migration, the historical watershed of the Holocaust, and his high hopes for the newly founded State of Israel.

Do you want to write a spotlight on your dissertation or thesis, or want to recommend someone to do one on theirs? Get in touch with the SCS Blog’s Editor-in-Chief, T. H. M. Gellar-Goad!

Authors