iandudum

June 2, 2022

In the latest issue of the CADW magazine, the organ of Wales’ official heritage body, the discussion of the Roman fort at Caerleon was accompanied by a graphic designed for children on the subject of Roman dining. With a Horrible Histories-type tone, the cartoon features a boy asking his mother if his friend can stay for dinner. “I thought we’d go Italian,” says his mother, but it’s not the demanded “Pasta? Pizza? ICE CREAM?”; rather, “Rich Romans had things like…Parrot heads or…dormice…and … sea urchins maybe” (to which the boy says “I feel sick”). But the “lush” counteroffer of fast food “meat patties in bread” — “Roman burgers” — is quickly scotched by the obligatory “fermented fish gut sauce”: the dog says, “Not even I’m eating that!” The closing reference to garum here, seen as undeniably negative, underscores the complex nature of our response to research on ancient foodways; one wonders what would happen if Worcestershire sauce, as standard in Welsh rarebit, were revealed to readers as similarly derived from fermented fish.

Figure 1: Garum. Image courtesy of Stu Spivack via Creative Commons.

For another flavor of contemporary general interest, which is burgeoning apace, in ancient food, one might sample several of the recipe-driven videos on the YouTube channel, “Tasting History with Max Miller”, currently with 1.2 million subscribers. These excellent forays into, and recreations of, historical cooking are helmed by not an academic or a chef but an enthusiastic and knowledgeable ex-Disney employee who is writing a cookbook around these recipes. As is typical in a modern world saturated by podcasts on every subject and typified by the back-and-forth of personalized online reviews where everyone’s a critic, these videos are slick, feature branded channel-specific merchandise such as a garum-flashing T-shirt and hoodie (tagline: garum non bibis), and are sponsored by various companies keen to engage with potential customers. The channel’s most popular video, with almost 2.4 million views, features the making and tasting of garum by Miller. In subsequent episodes, a link is provided to Amazon, where you, too, can buy Matiz España’s “Flor de garum” (shipping to Britain is not possible, though, perhaps as a result of Brexit). And that outfit is not the only purveyor of apparently authentic garum, slightly different from the Italian “colatura di alici”: the Selo de Mar project run by the Lisbon-based restaurant and art collective Can the Can, backed by the Portuguese National Association of Manufacturers of Tinned Fish, also produces its own.

Figure 2: Spaghetti with colatura di alici. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

This juncture of the pandemic has featured the hospitality industry teetering on the brink, shored up by initiatives such as the UK government’s August 2020 “Eat Out to Help Out” scheme—not to mention the looming climate crisis and its interaction with agribusiness. We have to recognize that food is inherently political and bound up with the identity of its producers, preparers, and consumers. But some might question whether learning about Roman eating can have practical applications to these modern realities. How can recreating recipes for sow udder (a Roman delicacy), or even, at the other end of the scale of luxury, studying Cato’s fetish for cabbage be anything other than the preserve of privileged dilettantism?

I have three answers to this challenge.

Firstly, many modern eating practices are rooted in local communities, and promising work is now elucidating the links between modern Mediterranean cuisines and their ancient forebears, as for instance Erica Rowan’s brilliant AHRC-funded project, Negotiating the Modernity Crisis: Globalization, Economic Gain, and the Loss of Traditional and Sustainable Food Practices in Turkey. Such reclamation efforts have affinities with the activities of the Slow Food movement and allow the return of ownership and agency to the inheritors of long-standing traditions in danger of dying out.

Second, current research has taken an ecocritical turn, to focus on ancient attitudes to the environment: books in this vein include Rebecca Armstrong’s Vergil’s Green Thoughts; Clara Bosak-Schroeder’s Other Natures: Environmental Encounters with Ancient Greek Ethnography; and a collection of papers, Nachhaltigkeit in der Antike, edited by Christopher Schliephake, Natascha Sojc, and Gregor Weber. This last book forms an entrée to the idea of sustainability in ancient Rome, a culture which did not necessarily prize the husbanding and reuse of resources, though this, too, is becoming a focus of scholarship on ancient water rights (with two chapters in that volume), in archaeological research more generally, and for a doorstopper volume on Recycling and Reuse in the Roman Economy, edited by Chloë Duckworth and Andrew Wilson. While this may seem to take us away from ancient food, it is in the context of such analyses and debates that we must consider the claims of Sally Grainger, at the end of her trenchant monograph The Story of Garum, recently reviewed by the present author, that fish sauces were matured in amphorae while they were transported, and that a second batch could be produced and decanted into further reusable amphorae, once the first was skimmed off.

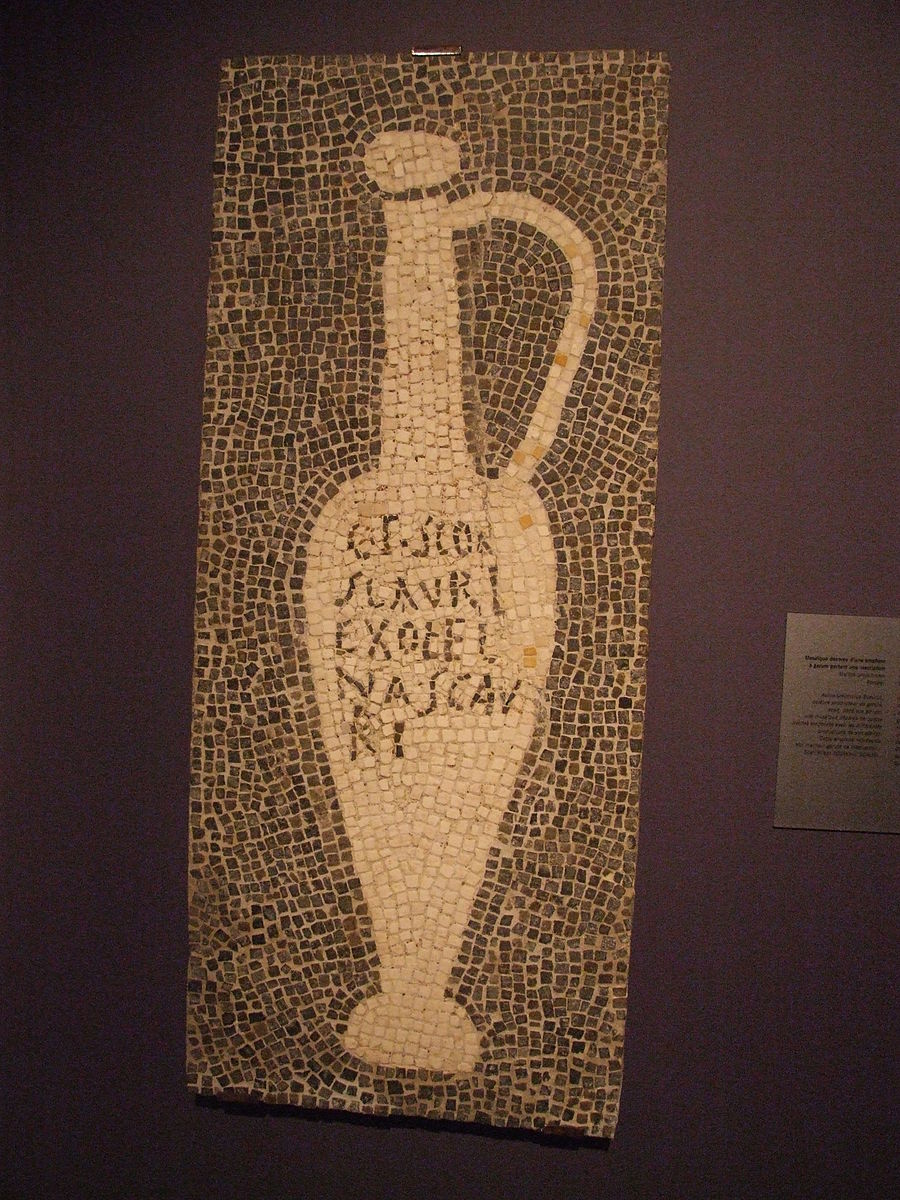

Figure 3: Mosaic depicting a "Flower of Garum" jug with a titulus reading "From the workshop of the garum importer Aulus Umbricius Scaurus." Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Lastly, food is an expression of the creative imagination. A better understanding of patterns in how the Romans ate shows us that — their lack of tomatoes and potatoes notwithstanding — our shared humanity has always been focused not only on where our next meal is coming from, but also on ways of displaying and appreciating it, at every level of society. This is borne out in such recent work as Laura Banducci’s Foodways in Republican Italy—which reveals shifts in the tableware and cookware at three Etruscan archaeological sites that suggest a move towards the presentation and sharing of meals—or Emily Gowers’ chapter in this past year’s Festschrift for Richard Hunter, which shows that Roman cooking always has pretensions to the creation of a new, blended world (e pluribus unum, as the U.S.A.’s Great Seal nearly quotes from the pseudo-Virgilian Moretum), often through apparently nugatory wordplay.

And who’s to say that trivia is useless? Our desire for a grasp on anything in this unstable world resulted, after all, in the keen appetite for Zoom quizzes in the first stages of the pandemic; the game “Wordle” has taken the online world by storm. As for myself, in the wake of making some light-hearted videos about Roman eating habits in literature, partly to keep myself entertained during lockdown, I too am now “fated to / Do nothing but brood / On food”: in my case, specifically the pickling techniques preserved in Book 12 of Columella’s De Agri Cultura. If the kimchi in my fridge were sentient, it would surely be proud.

Header image: Moretum and Roman bread. Image courtesy of Carole Raddato via Flickr.

Authors