Jennifer Roberts

April 3, 2020

In his history of the long and costly war between Athens and Sparta, the historian Thucydides explained that he had written his narrative to be “a possession for all time” and to be of assistance to those of future generations “who want to see things clearly as they were and, given human nature, as they will one day be again, more or less."1 Thucydides was a shrewd observer and analyst of human behavior, and his work has frequently been cited in times of crisis by those who see patterns in history. At the famous ceremony dedicating the battlefield cemetery at Gettysburg in 1863 at which Lincoln also spoke, former Secretary of State Edward Everett delivered a eulogy that interwove contemporary allusions with Thucydides’ rendition of the funeral oration the Athenian statesman Pericles had delivered after the first year of the war in 431 BCE.2

Figure 1: Abraham Lincoln (in the center) at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on November 19, 1863 (Public Domain).

In 1915, snippets from the speech were displayed on buses in London to fortify passengers for the war that had broken out the year before, and four years later President Woodrow Wilson would reread Thucydides’ history on his voyage across the Atlantic en route to the peace talks at Versailles. Decades later, during the war in Vietnam, Thucydides’ comments on the Athenians’ disastrous expedition to faraway Sicily were often quoted by journalists and politicians alike. Writing in 2002, political theorist Robert Kaplan proclaimed Thucydides “the surest guide to what we are likely to face in the early decades of the twenty-first century.”3 While the the text is collectively poignant, Thucydides’ careful description of the horrific plague (2. 47-54) that broke out in Athens shortly after the beginning of the war and his shrewd analysis of people’s response to it stand among the most memorable passages in his narrative. What follows below is an analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic as I suspect that the astute psychologist Thucydides might have written it.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Jennifer Roberts, an American, wrote the history of the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning at the moment that it broke out, and believing that it would be a horrific illness and of greater interest than any other in our lifetime. This belief was not without grounds, for by the beginning of spring in the year 2020 over a million people had been infected in over 150 countries, of whom more than 50,000 had died. Indeed this was the most frightening pandemic known to those alive at the time, affecting not only the Americans but a very large part of the world. No parallel health crisis had been known in the 21st century, for although the H1N1 flu of 2009 had claimed many lives, it was estimated that about a third of those over 60 had immunity to it, whereas nobody had immunity to COVID-19, which was particularly lethal to those in that age group.

Figure 2: Interactive Coronavirus COVID-19 Map from Johns Hopkins University (Screenshot on April 3, 2020, Copyright 2020 Johns Hopkins University, all rights reserved, used by permission).

With reference to the speeches quoted in this account, some were delivered before knowledge of the virus was widespread, others while it was raging; some I heard myself on television, others I read in newspapers and magazines and on the internet. It is therefore not difficult for me to check them in my notes, and readers may be confident that they were delivered just as they appear here; there is no need just to make the speakers say what was in my opinion demanded of them by the various occasions, adhering as closely as possible to the gist of what was actually said. Never in the memory of those alive at the time had there been so much panic. The fear was magnified by the uncertainty, both the uncertainty of the doctors about the probable course of the pandemic and the uncertainty of the people as to how much of the information coming their way could be trusted.

It was believed that the virus had come from China. As a consequence, a number of people of Asian descent were assaulted in the street, both in the United States and elsewhere.4 By the third week in March, however, casualty figures in Italy had surpassed those in China. More men died than women, and it was speculated that this was because more men than women smoked, which weakened the lungs; some, however—particularly women—suspected that men washed their hands less frequently, and that this was a factor. Others pointed to the generally greater resistance of females to disease, with the exception of autoimmune disease, to which women were more vulnerable than men.

Health care workers were the first to treat the disease, but as it was new, they were at a loss as to how to approach it, and they died in large numbers. The principal mode of transmission was thought to be respiratory droplets, and the knowledge that these might travel as much as six feet from someone who was sneezing or coughing caused considerable alarm in the populace. This fear was compounded by the news that touching a surface that had been touched by an infected person and then touching one’s eyes, nose, or mouth could transmit the virus as well, and people searched the internet frantically for information about just how long the virus could survive on various surfaces—plastic, stainless steel, cloth. What people did not know caused just as much fear as what they did know.

Old stories about earlier epidemics were revived and filled the populace with terror. Some recalled Sylvia Browne’s best-selling book End of Days published in 2008, in which Browne predicted that around 2020 a dreadful pneumonia-like illness would spread throughout the globe, making breathing extremely difficult and resisting all known treatments.5 Leaders in the United States and Britain tended at first to view the disease primarily as a political liability to be plastered over, mimicking the totalitarian government of China, where ophthalmologist Dr. Li Wenliang was detained by the police and forced to retract the alarm he had sounded about the illness. Within weeks Dr. Li contracted the virus from an infected patient and died.6 Other leaders like Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand and Angela Merkel in Germany addressed their constituents in more thoughtful televised addresses that led listeners to believe their health was the government’s primary concern. In time, the British prime minister himself developed the virus, and the American president came to acknowledge its seriousness, declaring that people would have to suspend their customary daily occupations and remain at home until at least the end of April.

In the United States, the problem was compounded by a widespread distrust of the methodical gathering of evidence, experimentation, and attempts to understand the principles of nature; a distrust that had been fostered by oligarchs who worried that awareness of climate change would result in curbs on commerce. This distrust had also become an increasing problem among some, though not all, religious people, particularly those known as evangelicals, who had gone so far as to oppose the teaching of evolution in public schools. Religion, however, not only failed to prevent the spread of the virus but indeed in many cases accelerated it as eager parishioners. Convinced that their piety would protect them against the virus, sickened in large numbers after attending church and infected others as well.

What lay behind the opposition to the “social distancing” many city and state governments had dictated was a large dose of wishful thinking, the same kind of thinking that had led to the rejection of climate science. Since sacrifice in the cause of preventing contagion was unpleasant, so people persuaded themselves, it could not possibly be necessary, just as it could not really be necessary to convert to solar energy or small cars or to cut back on air conditioning or flying. At the same time, preoccupation with money and material things blinded many people to the sanctity of life. When it began to look as if this distancing might have to go on for quite some time, it was curious to see people who had proclaimed themselves “pro-life” because of their vigorous opposition to abortion suggesting that the death of older people was a perfectly acceptable price to pay for resuming the customary routines of normal life so as not to imperil the economy.

The suggestion of Dan Patrick, Lieutenant Governor of the state of Texas, that grandparents should and indeed would be willing to die to ensure a healthy economy for their grandchildren embodied the kind of brutality to which the fear of the virus led.7 A pandemic like this one, which robs us of our daily necessities, is a harsh teacher. As happens often in times of crisis, there was a sharp divide between the responses of the city folk and the country folk. The population density of urban areas led the virus to jump quickly there from one person to the next; because people were more spread out in the countryside, initially it sometimes happened that so few people sickened there that the populace found it difficult to take the threat seriously and to observe the prescribed social distancing protocol, and many outside the cities deeply resented being ordered to curtail their activities and labeled the government’s intervention “tyranny.” Many young people on Spring Break congregated in groups and thus posed a risk not only to themselves but to older people with whom they came in contact.

The American president proclaimed that soon his people would make an infusion that would render its recipient immune to the disease, even though the investigators who make such infusions warned that it would take a year a year and a half to achieve.8 A man in the state of Arkansas died after medicating himself with chloroquine, a substance that Trump had suggested might be curative, thus taking advice from a man who was so ignorant about medicine that he had no idea that anyone could die of the flu, a disease which routinely killed about a third of a million people a year.9 Dr. Anthony Fauci, who had devoted himself while at university to the study of Greek and Roman literature and had now come to direct the American National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, struggled to maintain his composure while correcting the misinformation as tactfully as he could. He was several times seen on television placing his hand in front of his face to conceal his incredulous laughter as the President was speaking.

Like all crises, this one brought out both the worst and the best in human nature. Though many were paralyzed by terror and cowered in their homes, fearful even to shop for groceries, there were health care professionals and many other citizens who placed themselves in danger in order to help their neighbors. Others made generous donations of money to people they had never met. Many women and even some men volunteered to sew masks, of which there was a shortage, to help those most at risk. For the same upheaval that led some to put self-preservation above all else moved others to a contemplation of the human condition and concomitantly to new heights of compassion.

Figure 3: Illustration of the COVID-19 virus (Photo Credit: U.S. Army).

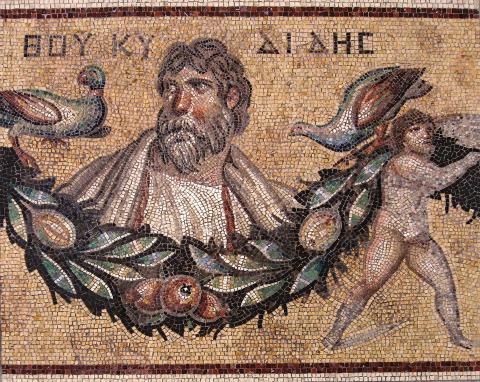

Header Image: Thucydides mosaic from Jerash, Jordan, 3rdC CE (Public Domain via Wikimedia).

_______

[1] Thucydides: The Peloponnesian War, trans. Walter Blanco, eds. by Walter Blanco and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts (New York: W. W. Norton, 1998), 2. 22. 4.

[2] Reproduced in Garry Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America (New York: Simon & Shuster, 1992), 213-47.

[3] Robert D. Kaplan, Warrior Politics: Why Leadership Demands a Pagan Ethos (New York: Random House), 22.

[4] Jack Guy, “East Asian student assaulted I ‘racist’ coronavirus attack in London,” CNN, March 3, 2020; Anna Russell, “The Rise of Coronavirus Hate Crimes,” The New Yorker, March 17, 2020; Alexandra Kelley, “Attacks on Asian Americans Skyrocket to 100 a Day Amidst Coronavirus Pandemic,” The Hill, March 31, 2020.

[5] Sylvia Browne and Lindsay Harrison, End of Days: Predictions and Prophecies About the End of the World (New York : Berkley Press, 2008).

[6] Chris Buckley, “Chinese Doctor, Silenced after Warning of Outbreak, Dies from Coronavirus,” The New York Times, February 6, 2020.

[7] Celia Viggo Wexler, “Coronavirus has Donald Trump and Dan Patrick ready to sacrifice older people,” March 26, 2020, nbcnews.com.

[8] Jan Hoffman, “President Trump on Vaccines: From Skeptic to Cheerleader,” The New York Times, March 11, 2020.

[9] Theresa Waldrop, Dave Alsup and Eliott C. McLaughlin, “Fearing coronavirus, Arizona man dies after taking a form of chloroquine used to treat aquariums,” CNN, March 25, 2020.

Authors