Justin Biggi

August 29, 2019

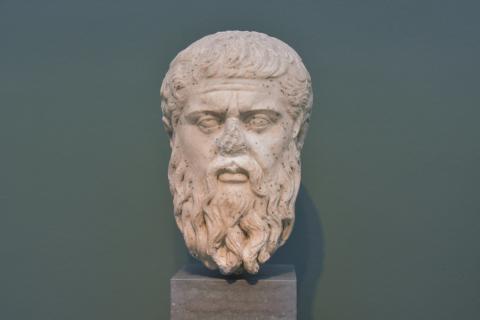

In March of 2019, Jordan Peele's Us was released in theaters. Much like his previous project, Get Out (2017), Us took the horror world by storm. Unlike Get Out, whose direct references to U.S. racism were the foundation of the plot, Peele left Us intentionally vague; allowing for a flurry of online theories to be born as to what his intended meaning may have been. To those with a knowledge of ancient philosophy, however, Us appeared to be a modern horror version of Plato's allegory of the cave.

The plot of Us is a summertime comedy gone awry, with the Wilson family finding itself pursued by their murderous doppelgängers, called the Tethered. The Tethered have freed themselves from their underground prison and wish to exact revenge on the people living above. Adelaide, the mother of the family, recognizes and knows the Tethered, since she was previously traumatized by her own double as a child, while she was on vacation at the same Santa Cruz beach. Instead of the chained prisoners in Plato’s allegory, there are the Tethered, trapped in their tunnels. Instead of the philosopher, there is Red, Adelaide's double, who, made aware of the Tethered's plight after her encounter above ground with Adelaide, is hell-bent on revenge.

Eventually, it is revealed that the Tethered were created as part of a failed experiment aimed at controlling the people living above ground. While they are exact physical copies of their counterparts, whoever created them was unable to replicate the soul, leaving them stripped of any free will of their own. Left to their own devices, the Tethered continuously mimic the actions of those above, slowly losing their minds in the process. Furthermore, Red explains how, when people above were performing seemingly mundane actions, like enjoying presents or a hot meal, the Tethered were forced into monstrous equivalents of those actions, such as playing with sharp objects or eating rabbit, “raw and bloody”.

Peele's imagery of prisoners trapped underground, whose lives are poor imitations of what exists above, recalls Plato's allegory of the cave—albeit in a much gorier fashion. Here, prisoners are chained together, unable to move, and cannot escape the confines of the cave they are kept in. Their world is reduced to the projected shadows of objects from the world above which are paraded behind them: to them, “reality [is] nothing else than the shadows of the artificial objects” (Rep. 7.515c).[1] The world outside, to which the objects belong to, illuminated by the light of the sun, is unknown to them.

In Plato's allegory, the latter world represents the perfect world of Forms, which are not perceived directly but mimicked by the shadows in the cave, which represent that which we interact with every day. Limited to what they can see, the prisoners are kept ignorant of the world above until one of them manages to break free and climb to the top of the cave, finally witnessing the outside world. In Plato's work, this enlightened prisoner is a representation of the philosopher, who truly understands the difference between the physical world and the world of Forms, and therefore can access true knowledge.

The main difference between Plato's prisoners and Peele's Tethered lies in the fact that Plato's prisoners are simply misguided, and, in the allegory, have no equivalents in the world of Forms, while the Tethered's entire identity is that they are apparently imperfect copies of those who inhabit the world outside their tunnels. The Tethered are therefore both Plato's prisoners and the shadows the prisoners are forced to look at: trapped underground, and separated from a world they are supposed to be the ugly side of.

A further layer is added when we take into consideration Plato's theory of language. In Plato, language is a conundrum: it is both the only tool available to the philosopher to successfully reflect on the surrounding world, and also an inherently flawed system, as it is created by a fallible, human intellect.[2] The Tethered can fit within the definitions of such a conundrum: firstly, their use of language is (on the surface, at least) imperfect –– they communicate using grunts, yells and gestures. Given the Tethered's in-world explanation, this can easily be seen by the audience as a poor(er) imitation of our own language, further extending the correspondence between Peele's imagery and Plato's writing.

A second parallel lies in the Tethered being created by a mysterious (but inescapably human) “They”. The Tethered become the imperfect tools through which the Wilson family and, in particular, Adelaide, are forced to examine themselves and the way they see the world. The Tethered are the (supposedly) imperfect reflections of our (supposedly) perfect selves. Literally created by humans, they narratively become the language through which this analysis must take place. Even on a meta-textual level, the Tethered's existence forces the audience to confront their own reality through their corrupted, broken, existence: they are imperfect, man-made, and they are the only way we can confront our own demons—whether we want to or not.

Once more, we return to Red, Adelaide's Tethered, who most closely corresponds to Plato's philosopher. While all of the other Tethered use a language made up of grunts, yells and gestures (which Red herself uses to communicate with her family), Red is the only one who is capable of what the audience can recognize as human speech. This fact is left largely unexplained, until the final twist is revealed: Red is the original Adelaide, who then-Red (now-Adelaide) kidnapped during their childhood encounter, and trapped underground in her place.

Red grew up in the world above, becoming Adelaide, while Adelaide grew up trapped in the underground tunnels, and became Red. The Tethered's bloody revolution, aimed at eliminating their above-ground copies to take their place, is sparked by Red's anger at the situation she found herself in. This final twist has given birth to a frenzy of discussions, as it abruptly forces the viewer to re-evaluate their entire movie-going experience and their approach to the narrative until now.

Us asks audiences to confront the reality of the modern-day U.S., still so unwilling to acknowledge its legacy of violence and imperialism, built on the backs of enslaved people. Peele presents the audience with the discovery that, in a certain sense, we had been rooting for the villain all along. This pushes the viewers to seriously interrogate the nature of both the Tethered and their counterparts, and to question who is or isn't the bad guy. It is in the final twist that Us appears most distant from Plato's own allegory of the cave. Plato's writing, while complex, lacks any ambiguity. The philosopher is just, and the prisoners misguided. But Jordan Peele's doppelgängers are Plato's prisoners for a modern, alienated 21st century America, whose inhabitants are more aware of and broken by capitalism, white supremacy, and inequality than ever before.

Peele casts his own philosopher as Red, Adelaide's double, who is the only one aware of the connection that exists between the Tethered and their counterparts above, much like Adelaide is the only one who knows of the Tethered's existence. Unlike Plato's philosopher, who returns to the cave only to be faced with ridicule and distrust (Rep. 7.517a), however, Red's awareness of the outside world consecrates her as the Tethered's chosen one. She is destined to lead them to the light in a bloody revolution. When asked who the Tethered are, Red triumphantly answers: “We're Americans”. In this way, she cements her awareness of the Tethered's identity not as simple copies of the U.S.' inhabitants, but, in their isolation and horrific living conditions, as images of those on whose backs U.S. society was built.

Header: Bust of Plato, Roman copy of a Greek original, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen (Image by Richard Mortel under a CC-BY-2.0).

[1] Translation by Paul Shorey.

[2] See Partee, M. H. (1972). “Plato's Theory of Language.” In Foundations of Language VIII.1 (pp. 113 – 132). Springer Publishing.

Authors