Katherine Blouin

January 14, 2019

Chanel took over New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Arts on December 4 for its annual Arts et Métiers fashion show. This year’s theme? Egypt. Except that, in many ways, it was not. What, and most importantly, who was showcased, then? The answer is unsurprisingly predictable, yet for this very reason, it powerfully illuminates the current, Orientalist and colonial reception of ancient Egypt in contemporary fashion and pop culture, and the ways in which this reception hasn’t changed much (if at all) since Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of the country in the late 18th century.

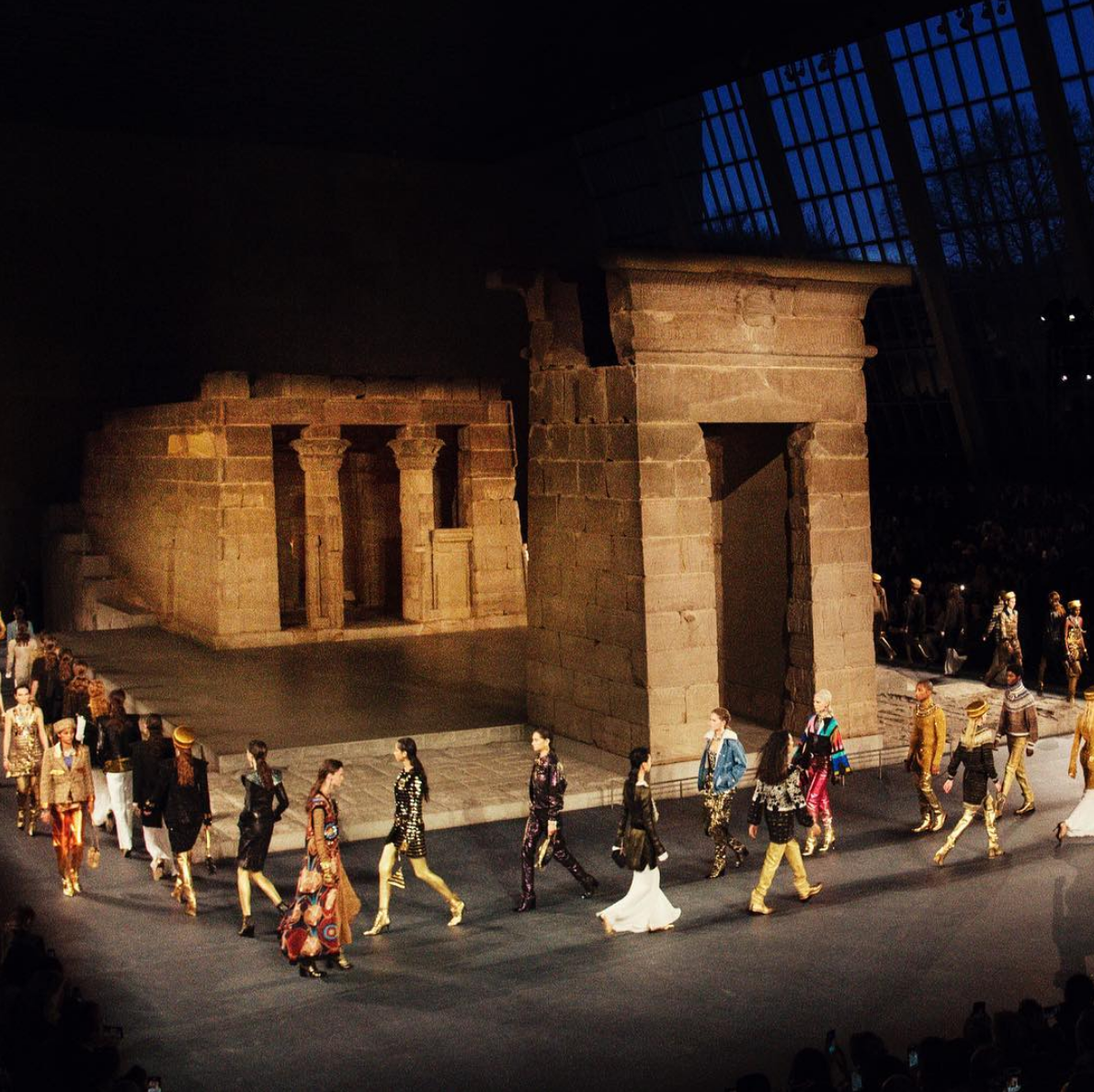

The yearly Arts et Métiers show began in 2002. It aims at showcasing the wide-ranging array of Métiers d’art that are part of Chanel under the Paraffection umbrella. The event is staged in and pays tribute to cities that are connected to the life of Gabrielle Chanel: Paris, mostly, but also Dallas, Edinburgh, Salzburg, Rome, Hamburg and, this year, New York, a place that Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel first visited in 1931, and where she returned in 1939 as one of France’s representatives of the “Couture and Perfumery” during the New York World’s Fair. The Fair’s theme was “The World of Tomorrow“. Yet despite, or perhaps rather because, its futuristic, consumerist craze, that ” tomorrow” proved to be a grim one, for within six months of the fair’s opening, World War II broke. This might be one of the reasons why, apart from Chanel’s emblematic tweeds and geometric patterns alluding to the city’s skyscrapers, Karl Lagerfeld’s designs avoid any obvious reference to the New York of the late 1930s. Instead, the designer proposed a nostalgic, Orientalist take on the city’s – and on France’s – relationship to Egyptian Antiquities. His New York is an Egyptomaniac one, whose focal point is the Temple of Dendur.

Figure 1: “Details of the 2018/19 #CHANELMetiersdArt collection … including gold and scarab beetle adornments by #Montex.” (Image and caption: Chanel’s Instagram)

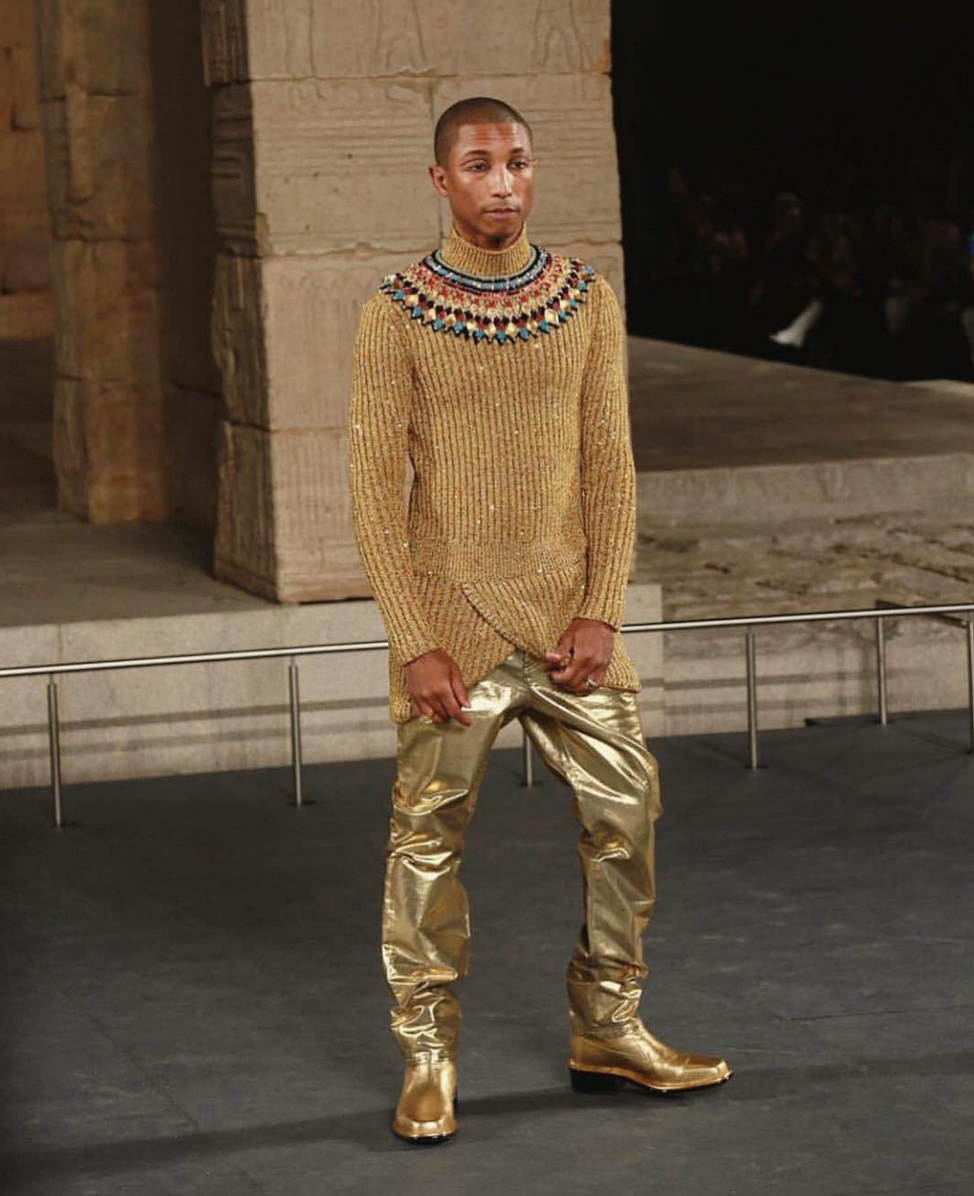

Set around the temple, the 15-minute procession of Hatshepsut-eyed models was a spectacular display of craftsmanship, and a testimony to Karl Lagerfeld’s unstoppable creative genius. The theme was further enhanced by the musical soundtrack, which began and ended with Egyptian Lover’s 1984 Egypt, Egypt. There were dozens of mostly white, but also black, brown, and Asian models, whose long, regal silhouettes walked in circle around the sandstone temple. There was gold, black, lapis lazuli blue, turquoise and silver. There was a dress covered in feathers arranged in chevrons, pleated skirts and an overabundance of intricate, heavy jewels. There were pyramid handbags, metallic gloves and collars made of dyed reptile skins, gems and pearls. There was Pharrell walking in an all-gold ensemble. There were dresses covered in hieroglyphic-like graffiti, diaphanous underskirts that echoed Hathoric dresses and mummy wrappings. There were lions, lotuses and scarab beetles, gilded tweeds, beaded fishnets and golden flats.

Figure 2: Pharrell walking the runway Chanel Arts et Métiers 2018 show (Image: Pharrell’s Instagram)

Figure 3: “Hand-applied feather marquetry by #MaisonLemarie at the #CHANELMetiersdArt show in the @metmuseum, depicting a graphic reinterpretation of Egyptian paintings” (Image and caption: Chanel’s Instagram)

The temple of Dendur’s impassive presence acted as the stage’s pivotal anchor. The getaway and temple were originally located on the Nubian site of Dendur, south of the traditional Egyptian border at Aswan. The ensemble was completed in 10 BCE, that is twenty years after Octavian-Augustus’ victory over Mark Anthony and Cleopatra at Actium and the ensuing annexation of the Ptolemaic kingdom to Rome’s Empire. The temple, thus, like several of the most popular temples of Upper Egypt (Edfu, Dendera, Kom Ombo and Philae) was built (in great part) under Macedonian and Roman rules. It is primarily dedicated to Isis of Philae, a name that refers to the island of Philae (c.80 km north of Dendur), which hosts a larger temple to Isis. In addition to her, her spouse Osiris, as well as Pedesi and Pihor, two brothers who might have been deified sons of chieftains, and the Nubian gods Mandulis and Arsenuphis, are also honored. Like the several other Egyptian temples commissioned by Augustus, the Dendur one follows native architectural, iconographical, epigraphical standards. Augustus’ regal profile shows him in full Pharaonic garb, surrounded by hieroglyphic texts. If you are not an Egyptologist, you cannot tell the reliefs date from the Roman period and were commissioned by a foreign ruler.

Figure 4: “Karl Lagerfeld was inspired by Egyptian civilisation and the spirit of New York for the 2018/19 #CHANELMetiersdArt collection dedicated to the savoir faire of CHANEL’s Métiers d’art, presenting it in The Temple of Dendur in the @metmuseum” (Image and caption: Chanel’s Instagram).

Fast forward almost two millennia, to the 1960s, and Lower Nubia, a region that stretches from southern Egypt to northern Sudan, found itself about to be submerged following the construction of the High Aswan dam. Lake Nasser, the vast reservoir lake called after the then President of Egypt Gamal Adbel Nasser, eventually covered c.2,000m2 of land, forcing the relocation of local, Nubian communities, and the destruction of many archaeological sites. Ahead of its creation, the UNESCO set up the “International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia“. Fifty countries took part in the campaign, including the USA, which offered the biggest monetary contribution and thus were the first to choose their archaeological “gift” among some of the salvaged monuments. Their pick: The temple of Dendur. In 1965, Egypt officially gave the USA the temple and its getaway and two years later, after a competition among interested American cities and institutions, President Lyndon B. Johnson offered it to the Met. The dismantled structure was shipped to New York, before being restored and rebuilt within the Sackler Wing. Bordered by a reflecting pool and naturally lit thanks to a large bay window that overlooks Central Park, Gallery 131 is more than a museum display of Pharaonic-style sacred architecture and Nubian heritage. It is, also, a rendition of Egypt’s topography that acts as a versatile, socio-cultural space of its own.

Contrary to what the temple itself and the monochromic tones of the room might indicate at first glance, it was originally, like all ancient Egyptian (and ancient Mediterranean) temples, painted in deep, vivid colors. Just like for statues, what mostly remains today of these ancient buildings is their bone structure. Likewise, average ancient Egyptians did not walk around covered in gold, lapis lazuli and turquoise, looking like Tutankhamun’s funerary mask or Isis Almighty. Nope. But this doesn’t matter. What matters is that Chanel’s Egypt is a familiar place for western audiences. And we can conveniently blame Napoléon and his army of scientists and scholars for it.

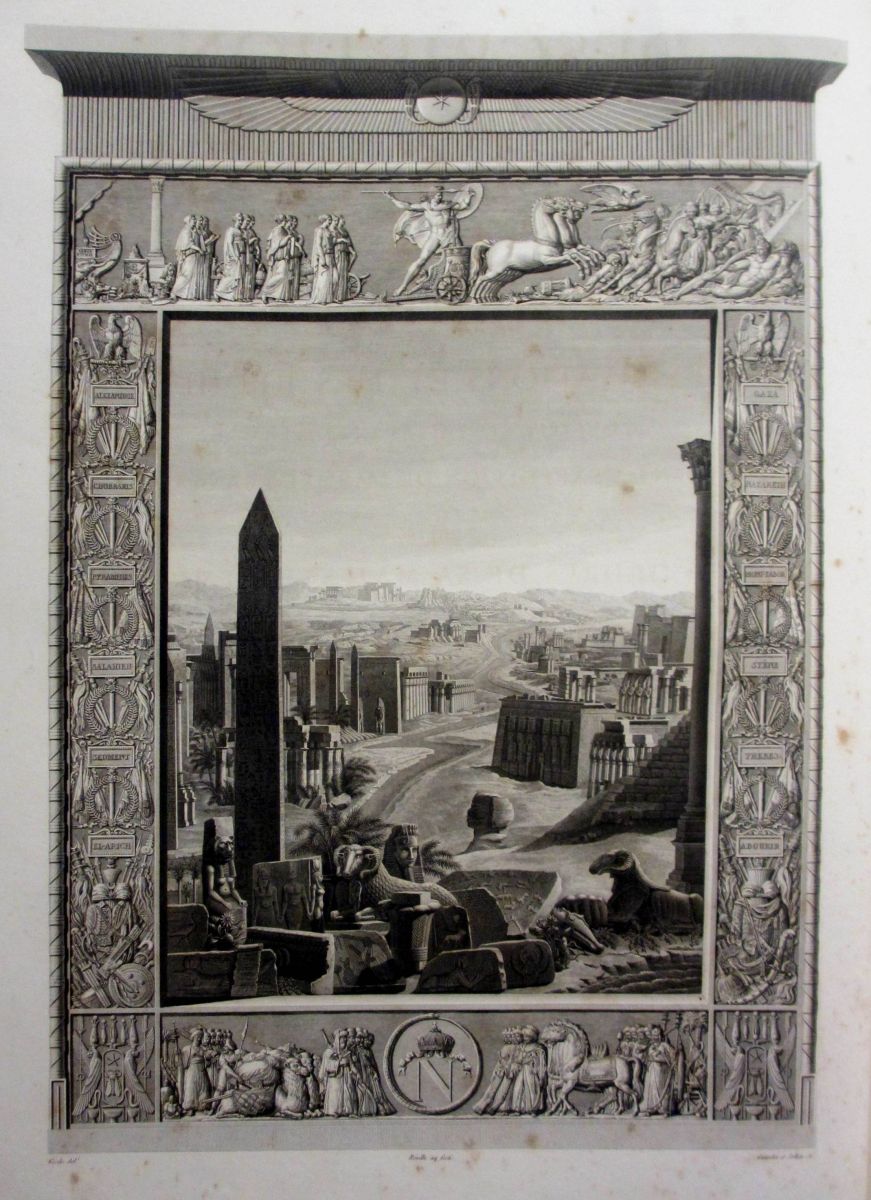

When Napoléon Bonaparte added Egypt to his empire in 1798, he brought with him a contingent of French engineers, artists, and scholars, whose duty was to document all aspects of ancient and modern Egypt’s landscapes, ruins, cities, villages and customs. The final result was the Description de l’Égypte (“Description of Egypt”, thereby DE), a massive series of thirty-four, almost 1m2 volumes published in Paris between 1809 and 1829. The DE was an imperial vanity project; one whose scholarly and cultural ambition was to compensate for Napoléon’s loss of Egypt (and of the Rosetta Stone) to the British in 1802. If France didn’t occupy Egypt militarily anymore, it still, so the DE signaled, controlled and produced the knowledge pertaining to its past and present. Edward Said has brilliantly analyzed the implications of this enterprise and the foundational impact it had on Orientalist scholarship ever since in his seminal work Orientalism.

Figure 5: Description de l’Égypte, frontispiece page (Full text available via Hathitrust).

I’ve been obsessed with engineer, drawer and member of the Expédition d’Égypte François-Charles Cécile’s 1809 frontispiece page of the DE for a while now. To me, this black and white work is the foundational articulation of all “Western” (that is European and North American) political, cultural, and scholarly treatments of Egypt ever since. The frontispiece is also a wonderful pedagogical tool, which I’ve been using in several of my classes. I often say that should Classicists and Egyptologists spend more time mulling over it, we would save ourselves a great part of the psychoanalytical work our disciplines remain in dire need of. For almost all of the ensuing representations and receptions of the country replicate its fundamental characteristics.

So, what do we see?

We see two distinctive components: A Classically-inspired frame, and an ‘Egyptianizing’ center. The central drawing is a shrunk landscape of Egypt that runs from the Mediterranean shore on the top right, to Aswan, at the rear. A selection of Pharaonic-style monuments are set along the meandering Nile, which acts as the drawing’s topographic anchor and gives rhythm and further perspective to the composition. The only dissonant element is the so-called column of Pompey, in reality the sole remaining column of Alexandria’s famous Serapeum (temple to Sarapis). The fact that the column was a common feature of European touristic and cartographic representations of Egypt in the early modern period might explain why it made it into the frontispiece despite its Greek look. Left of the column, “Cleopatra’s needle” stands out. The “needle” is in fact a reused granite obelisk from the reign of Thutmoses III that was first erected in Heliopolis. Together with a second one that now stands in London, it was moved to Alexandria in 13 or 12 BCE in order to be integrated to the city’s Caesareum (temple to the deified Julius Caesar whose foundation dates from Cleopatra VII’s reign). In 1880, the Khedive Ismail offered it to New York, and it now stands in Central Park.

Figure 6: Statue of the Nile, Piazza del Campidoglio, Rome, Italy (Image by Katherine Blouin and used by permission).

In lieu of frame, the composition is surrounded by a neo-Classical frieze that pays tribute to Napoléon’s military prowess and civilizing mission in Egypt. It also contains to symbolic references to his Italian campaigns (1792-1802). The top register features Napoléon-Apollo followed by Muses-like female personifications of the Arts and Sciences. Naked except from a flowing cape, the French emperor rides a four-horse chariot. And this is not any random four-horse chariot, but the bronze quadriga looted in Constantinople’s hippodrome by the Venetians during their sack of the Byzantine Empire in the context of the fourth crusade (1202-1204). The bronze horses were embedded in the central façade of the Saint Mark basilica, but they’ve since been replaced by a replica, the original being housed in the basilica’s Treasury. Thus riding his Constantinopolitan/Venetian horses, Apollo-Napoléon rolls towards the right of the frieze, preceded by the imperial eagle. His targets? The defeated Mamluks, who are portrayed on horseback fleeing Egypt. The latter is represented at the bottom right of the register as a reclining bearded man holding a cornupia. This personification of the Nile River corresponds to the statue that now stands, together with a similar statue of the Tiber River, in Rome’s Piazza del Campidoglio. In Antiquity, the pair was part of the city’s Serapeum. On the left and right-hand sides of the frame, one sees a series of Roman-style military standards with the name of battles Napoléon’s army won during its campaigns in Syria-Palestine and Egypt. At the bottom, Magi-looking Mamluks and their camels are seen bringing tributes to Napoléon, who is represented by a crowned letter N. The message couldn’t be clearer: Pharaonic Egypt’s monumental glory is enframed, contained and enlightened through the arts and sciences by Napoléon, who is portrayed as the embodiment and promoter of a French, Classically-fed imperialism, and the antidote to Oriental despotism.

If that is what we see when we look at the frontispiece, then what is not there?

As a matter of fact, we don’t really see Egypt. There are no living beings, be they animal, humans or, except a few palm trees here and there, vegetal; no villages; no cities; no fields or agricultural landscapes; no dikes, canals, roads, boats or harbors; no life. The DE‘s Egypt is an empty, still space whose monuments are up for grab.

Chanel’s Met show represents yet another rendition of the DE‘s frontispiece page. A swirling one that is, where temporality is articulated according to a cultural divide: on the one hand, Egypt is firmly rooted in a grandiose, gilded and mysterious yet immobile past; on the other, that static, Oriental past is pulled forward and into the future by western know how. Model, photographer and Vogue UK contributor Laura Bailey’s take on the show eloquently testifies to how, despite its claim to innovation, the story proposed by Chanel is one we’ve heard many times before, one saturated with the same old Orientalist dichotomies: East and West; old and new; spirituality and technology; eternal, mysterious past and futuristic modernity. The same old story with the same old tropes, packaged as “futurism”.

Creation is turning the old into new.

Creation is spolia.

The term spolia is a Latin word that originally designated spoils of war. In modern scholarship, it refers to the practice of reusing and repurposing older precious objects and (parts of) monuments into more recent buildings and works of arts. While spolia have traditionally been associated with Late Antique art (and thus deemed less sophisticated than earlier, “original” works from earlier, “Classical” periods), the truth of the matter is, the practice has always existed. Rulers and artists have traditionally practiced spolia out of both practical (re-use of abandoned monuments and building materials; saving costs and time) and ideological (boosting one’s reign and socio-political or religious capital by associating oneself with a popular ruler, god or saint) reasons. In many ways, it continues to this day, from former factories-turned condos or restaurants to vintage fashion, to musical sampling, to the practice of excavating, collecting, and exhibiting older objects, monuments and bodies. It also includes the Met’s Gallery 131, as well as the Chanel show that took place in it.

For the Temple of Dendur is not the only Antiquity on display in Gallery 131 of the Sackler Wing. Two statues of Amenhotep III (c. 1390-1353 BCE) from the temple of Amun at Luxor stand in front of the water pool, as if to guard the temple. These were offered by the Egyptian Government in 1922. Towards the back of the temple’s left side, one also finds a pink granite sphinx of female pharaoh Hatshepsut (c.1479-1458 BCE) that originally stood in the ruler’s funerary temple of Deir el-Bahari on the westbank of Luxor, and that features prominently in the video caption of the show. The sphinx, which was found in the context of the Met’s 1926-1928 excavations, came to the Museum following a division of finds in 1931.

Figure 7: Temple of Dendur (Image is in the Public Domain and via the Metmuseum).

Just like the DE frontispiece, Chanel’s vision of Egypt is a disembodied one inasmuch as it draws its inspiration from artifacts found for the most part in funerary and religious contexts. What mattered most with the Paris-New York show was not Egypt per se; it was America’s, France’s, Chanel’s Egypt. Karl Lagerfeld’s Egypt is bookish and touristic, and this should not come as a surprise. How many of us are willing to experience Egypt beyond what we imagine it to be? From Napoléon to today, the country remains, for most audiences, a lifeless landscape made of sand and stones, of colossal monuments and sphinxes and obelisks. Egypt is a stage. Egypt is a fossil of a long-past imperial glory whose appropriation by the “West” can only be rationalized through its complete disconnect from everything that came after that purported “grandeur”, and especially the Arab conquest and the slow conversion of the country’s population to Islam.

It is to that effect telling to compare the New York show with the 2015 Dubai Chanel Cruise one. While the latter drew heavily from local craftsmanship, fashion codes and esthetics, and while it took place in Dubai itself and included a substantial amount of local guests, judging from the footages and pictures available online, modern and contemporary Egypt were completely absent, and so were living Egyptians and their culture, from the New York Arts et Métiers show. That there is a substantial market for Chanel in the Gulf States certainly justifies the choice of Dubai, and the same can be said of the 2009 Paris-Shanghai Arts et Métiers show, which was staged in Shanghai’s Bund area. More recently, Karl Lagerfeld wanted to stage the 2018 Chanel Cruise show amidst Greek ruins, but facing the refusal of Greek officials, he decided to recreate his vision of ancient Greece in Paris. What was his vision? Not colorful ancient Athens, but the white ruins that are left of it.

Figure 8: Chanel Cruise 2018 show (Image: Chanel’s Instagram).

The show’s set up recalls the 2010 Paris-Byzance and 2011 Paris-Bombay Arts et Métiers shows: Both were inspired by places located in the “East” (Turkey and India) yet staged in Paris; both are named after old toponyms (Byzance rather than Istanbul; Bombay rather than Mumbai) that echo European, Christian Empires; both drew heavily from local iconography, craftsmanship and esthetic codes, leading, in the case of Paris-Bombay, to discussion around cultural appropriation. In an interview given during the 2011 Paris-Bombay show, Lagerfeld said “India for me is an idea. I know nothing about reality, so I have the poetic vision of something maybe less poetic”.

What these fashion events have in common is their location in an imagined Orient; one whose relationship to Chanel’s esthetics resides in ideas surrounding its past, immemorial, imperial grandeur and exoticism. In places where the wealthy ruling class’ buying power is high and the (female) demand for French luxury fashion particularly strong, we see Chanel runways move East (Shanghai, Dubai). Otherwise (Turkey, India, Egypt), shows seem to have stemmed more from a desire to explore the western, French or American, gaze on foreign (past) lands and cultures than from a will to engage in an unmediated way with these locations.

Given that, one can hardly ignore how Chanel’s New York show was also staged so as to maximize the brand’s ability to tap into the current force, and therefore marketable potential, of Afrocentrist, Afrofuturistic and Afrosurrealist esthetics among African American and other black communities beyond the USA. Singer and Chanel ambassador Janelle Monae sums it up well: “I love that Egypt was an inspiration, a futuristic yet timeless place, and that’s what I got from the collection”. Chanel here follows Balmain in appealing directly to African-American customers by offering them pieces of design that tap into the central, ongoing role played by Pharaonic Egypt in Afrocentrist discourses. Beyoncé’s Nefertiti looks at Beychella? Olivier Rousteing for Balmain. The feathered hieroglyphic outfit she wore during her Global Citizens Festival set in Johannesburgh in early December? Olivier Rousteing for Balmain. Rousteing, a black designer who is known for advocating for more diversity in the fashion world, approaches Egypt from a deeply personal, future-oriented place. As Manon Renault has shown, both his and British creator Pam Hogg’s Egyptian references partake in a political agenda that draws from and contest the established (gender, racial) order.

.png)

Figure 9: Beyoncé’s custom-made Balmain look for the 2018 Global Citizen Festival: Mandela 100! (Image: Balmain’s Instagram).

Chanel’s idea of Egypt is a highly selective and curated one; one that speaks more of the creators’, brand’s and audience’s own positioning than of Egypt’s actual history, heritage and multi-layered culture. The thing is, Karl Lagerfeld’s and Chanel’s Egypt is not about Egypt. It is about Paris and New York. It is about the wealthy, Western “us”. It is about the ideas, the stories of Egypt that the world has been retelling itself again and again since 1798. It is about a fantasy of Egypt that sells. It is an impeccable, inspired, beautiful but ultimately truncated representation of peoples, cultures and histories; one that fetishizes the rich and the powerful; one that does care about Egypt only so far as it sends back to oneself the feeling that one can, too, partake in the riches, power, and enduring memory.

[This is an SCS blog cross-post with Everyday Orientalism , run by Katherine Blouin, Usama Ali Gad, and Rachel Mairs. Follow it here].

Header Image: Alan Roscoe (Pharon) and Theda Bara (Cleopatra) in the American drama film Cleopatra (1917) - publicity still- (Image via Wikimedia and is in the Public Domain).

Authors