Manya Lempert and Arum Park

November 9, 2020

Some months ago, a piece by Leah Mitchell and Eli Rubies on Classics and reception studies in the 21st century reiterated the importance of studying the reception of classical antiquity. It was a reminder that reception of classical material itself predates the scholarly field devoted to it. Its provocations overlapped with the suggestions of scholars such as Lorna Hardwick and Lowell Edmunds, namely that the interpretive benefits of reception cut two ways: not only can a source text help us understand a receiving text, but the receiving text can also help us understand the source text.

In a serendipitously complementary series of events, I became friends with Professor Manya Lempert. Although her scholarly home is in the University of Arizona’s Department of English, her work brings her into frequent and prolonged contact with ancient Greek texts. She is the author of Tragedy and the Modernist Novel. I asked her to speak with me about her book and her thoughts about the interpretive benefits of exploring the relationship between modern and ancient texts.

Arum Park (AP): Can you briefly describe what your book is about?

Manya Lempert (ML): The book is about what Greek tragedy meant to modern European novelists. I focus on four writers: Thomas Hardy, Virginia Woolf, Albert Camus, and Samuel Beckett. I look at their prose fiction and critical writings.

What stands out to me is that all four of them felt that a Greek tragic worldview was more true and more timely than contemporary non-tragic outlooks. They associated these mainstream, non-tragic views with Western capitalisms, imperialisms, and fascisms.

Greek Tragedy, on the other hand, freed them from a cultural expectation of stoic sangfroid in the face of loss. They developed a novelistic stage for mourning. Their narrators and characters cried out in pain. In multiple ways, their fiction was hoarse with lament and outrage. I think that this, for them, was its resurgent Greekness.

Figure 1: A short description of Virginia Woolf during her time in King's College London. Taken at Virginia Woolf Building (Image via Wikimedia).

AP: How did you get interested in Greek tragedy?

ML: I wanted to know why Greek tragedy meant so much to these writers who meant so much to me. Initially, I was more comfortable with philosophy than Classics, so I hoped that philosophy could bring me up to speed. I thought that Aristotle, for instance, could give me a working sense of tragedy. I thought that nineteenth-century philosophers of “the tragic” could teach me the basics. This was a very silly idea. I discovered that the philosophers’ interpretations of tragedy had little in common with my novelists’. There was more of a clash between the philosophy and the literature than a clarifying congruence. I realized that late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century philosophers and anthropologists were keen to locate their own ideas in Greek tragedy; the operative principle, it seemed to me, was that the cachet of the Classics would lend credence to their theories (of history, of psychology, of ritual). Perhaps literature is always a Rorschach test. We find what we seek. Still, I followed in my authors’ footsteps and turned to the Greeks directly. In so doing, I answered a methodological question: from whom would I derive my sense of Greek tragedy? From the novelists themselves, from influential theorists, or from my own analyses? Mainly I deferred to my writers. I flagged their departures from the theorists. I occasionally and sparingly commented on the Classical texts myself.

AP: You are really raising some interesting points! What you are suggesting, I think, is that the contours of tragedy are determined by the disciplinary perspectives of the thinkers approaching it. Or, more simply, tragedy means different things for different people. This might seem obvious, but what you are saying is that your novelists’ takes on tragedy rang truer for you than many of the philosophers’ approaches, right? And, ultimately, the novelists derived valuable insights from the Greek texts that eluded the philosophers?

ML: Yes, they did just that.

It seems to me that philosophers, in their writings on tragedy, sought to resolve or at least to minimize what we could call the problem of evil. I discovered classicists and critics who shared this view, who contended that philosophers from Aristotle forward had sought to sanitize tragedy, to contain its starkest intimations. A long tradition of commentators, I came to see, had been reluctant to recognize unearned and indefensible suffering. I found this same interpretive bias in studies of evolution: waste and pain in the course of natural history, said critics, must be justified. In the life sciences and philosophy, I encountered many apologists for pain. My argument in the book, however, is that these novelists understood Greek tragedy and Darwinian evolution to acknowledge suffering rather than to defend or alleviate it.

Figure 2: Library Walk New City. plaque for Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot (Image via Wikimedia).

AP: How did your research interests develop to bring you to this intersection with Classics?

ML: When I was a graduate student at Berkeley, my advisor suggested that I apply to a summer seminar that philosopher Simon Critchley was convening,“Tragedy’s Philosophy.” It was one of the happiest weeks of my life. Prior to meeting in person, we read the Greek plays in translation and a great deal of criticism and modern literature too. I spent months in preparation. I was there to learn, not to network or make a splash. I wasn’t a Classicist or a philosopher. Well, I was a closet Classicist. I found every play enthralling.

Readings and conversations kept drawing me back to Greek literature. For instance, one critical text that Simon asked us to read was Bernard Williams’ Shame and Necessity. Simon spoke of these lines in an opening lecture, I believe: “We are in an ethical condition that lies not only beyond Christianity, but beyond its Kantian and its Hegelian legacies. . . . In important ways, we are, in our ethical situation, more like human beings in antiquity than any Western people have been in the meantime. More particularly, we are like those who, from the fifth century and earlier, have left us traces of a consciousness that had not yet been touched by Plato’s and Aristotle’s attempts to make our ethical relations to the world fully intelligible.” This is fascinating to me. It provides one account of why modern writers found Greek tragedians so magnetic. It also explains why philosophical or religious accounts of tragedy were not likely to dovetail with modern writers’ art and ethics.

AP: Do you think that your novelists’ receptions of Greek tragedy were more “accurate” in some ways than philosophers’?

ML: I do feel this. But Plato’s wariness of tragedy is extremely interesting to me. What a sparring partner he is! And Hegel’s interpretations of Greek tragedy have been very influential. One synopsis of his thinking is that the Greek art form illustrates a dynamic of historical collision and transition. It can be stimulating to think about the accuracy of this reading, whether it holds true for literature or history. However, right now I prefer modern fiction as my interlocutor on the Greeks. Some former students and I formed a reading group. We first read Christa Wolf’s Medea, which offered some very rich insights! Next I’m reading Cherríe Moraga’s The Hungry Woman. I’m so interested in Moraga’s attraction to Medea and tragedy.

Figure 3: Cover of Christa Wolf's Medea: A Modern Retelling (1998) (Fair Use).

AP: What will English scholars learn from your work about the utility of Classics?

ML: I think that I have an answer to the reverse question, what Classics scholars might learn from an English book.

These modern writers made their own implicit and explicit claims about Greek tragedy and perhaps these are intriguing (rather than irrelevant and eccentric) hypotheses to test? Here is one example. Albert Camus, to my mind, derives much of his ethics and aesthetics from his understanding of Greek tragedy. In Greek tragic drama, he locates and celebrates moments of respite, amnesties from fate. These are the cornerstone of his own fiction and nonfiction as well. “Moments of being” were already a hallmark of modernism, even a cliché. But is Camus right that such moments – of release from fate’s clutches – populate Greek tragedies as well? From this question sprang a companion: did Greek and modern tragedies work negatively, making audiences desire what wasn’t there (reprieve, justice, understanding, security)? Or did they include a taste of these? Camus believed the latter, that in both ancient plays and modern fiction we catch glimpses of counterfactual worlds.

AP: It seems like you are saying that we can understand Greek tragedy through Camus (or, really, any of the other authors you write about). Are you suggesting that not only can we understand the way Camus thought of tragedy, but also that Camus’ understanding of tragedy can inform our own?

ML: That’s it. He gives us an interpretive schema to entertain. Oscar Wilde touted the critic as artist but I have grown fond of the artist as critic.

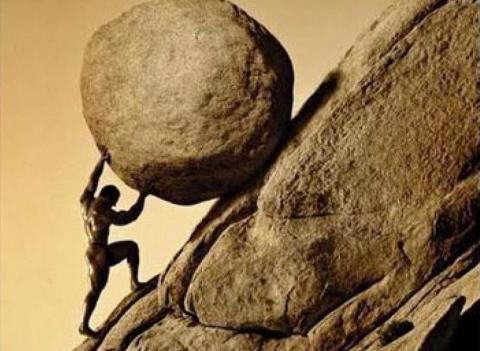

Camus repeatedly invokes a “tremendous remark” that opens Oedipus at Colonus: “Despite so many ordeals,” Camus paraphrases, “my advanced age and the nobility of my soul make me conclude that all is well.” For Camus, Oedipus finds that apart from his miseries, there are still modest grounds for affirmation. Touch is enough. A pittance is enough. Camus’s own tragic hero Sisyphus also “concludes that all is well” on the basis of “a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering.” This is the short interval when Sisyphus descends the mountain unburdened. For Camus, then, Oedipus’s modicum of contentment or Sisyphus’s hours of rest instantiate alternatives to their worst ordeals.

Camus’s point, I think, is not that tragic characters are reconciled to their protracted suffering, that they endorse it or pronounce its deservedness. They know, Camus writes, that “higher destiny . . . is inevitable and despicable” and that they cannot transcend or sidestep it. But they can affirm its antithesis. I love this idea. Sisyphean moments of liberation are intimations of a rival world. Small-scale pleasure in straitened circumstances is a template for change. It is the obverse of oppression, its tiny yet mighty antagonist. Slight or momentary happiness – when “all is well” – is so little. But it is also everything. It seems to me that if we look to Oedipus, Hecuba, Medea, or other plays, we can detect these glimmers of hope.

AP: What were your general attitudes toward and understanding of Classics before you began this project? How has the process of researching and completing your book informed or even changed your earlier impressions of what Classics was about?

ML: I was a novice and still have so much to learn. Critics in my field have tended to talk about modernism’s Classicism or Hellenism, and about epic, myth, and ritual in modern texts. They talk less about modernism and tragedy. However, two books on modernist writers and tragedy came out around when I finished my manuscript. They gave me such a wonderful sense of company! Both their authors were trained in Classics.

My work led me to think more concretely about how modern writers responded to Classical texts. Traversing millennia, they found kindred spirits. I came to see parts of their works as elliptical homages to a Classical precedent. But I didn’t begin reading about Classical reception studies until about a year ago, when I was starting to sketch a table of contents for an edited volume on tragedy. I didn’t conceive of my own work under the sign of Classical reception, until you did. In retrospect, I think that if I had been more conversant with scholarship in Classics, its conversations would have furnished me with brilliant questions (historical, formal, thematic) to pose to modern fiction.

AP: Thank you so much for this conversation, Manya––you’ve given me quite a lot to think about in terms of the many and various avenues we can take to enrich our understanding of Classics.

Authors