Merle Eisenberg and Lee Mordechai

May 28, 2021

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought historical epidemics into contemporary public awareness on a massive scale. Although ancient pandemics have been studied in detail since at least the 19th century, over the past year, outbreaks of the past have become apparently more relevant for what they might offer us today. Of course, the interest in historical pandemics seems to increase every time contemporary diseases draw public attention. Over the last three decades, HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and Zika, among others, have made headlines, increasing interest in past diseases, even if not on the same scale as Covid. Presentist concerns, unsurprisingly, drive historical research.

Venues such as the Washington Post now regularly discuss ancient and medieval pandemics, while it is common in public-facing articles to encounter debates over whether the Antonine Plague (circa 165–180ce) led to the end of the high point of the Roman Empire, the Cyprianic Plague (circa 250s) gave rise to Christianity, and the Justinianic Plague (circa 541–750) led to the end of the ancient world. Popular visualizations that contextualize Covid vis-à-vis earlier pandemics help answer our most pressing questions today: is Covid a unique event? How bad will it be?

What seems to lie behind many of these analyses and visualizations is the assumption that a pandemic’s impact is directly linked to its mortality. The dots between a disease’s outbreak, its supposed massive mortality, and the massive changes it thus supposedly wrought are, however, rarely connected. Instead, pandemics — in the pre-modern world in particular — have become black boxes that blur specific causes and effects in favor of large-scale narratives.

In a recent article in The American Historical Review, we answered a deceptively simple question: “Why do we assume plague was such a big deal in the ancient world?” In previous research, we had uncovered the weak evidence for the Justinianic Plague. Despite this paucity of evidence, it appears that the very mention of the word plague in an ancient or medieval context is enough to evoke a series of assumptions about the effects of the disease. According to this line of thought, the Justinianic Plague must have been significant, since we “know” that major pre-modern pandemics not only kill millions, but change the course of human history.

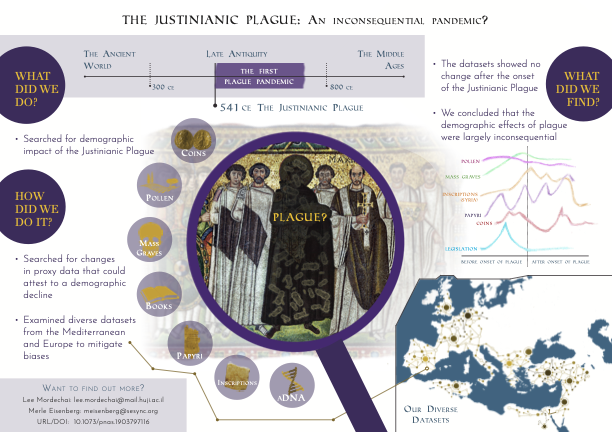

Figure 1: Infographic about the Justinian Plague. Image courtesy of Elizabeth Herzfeldt-Kamprath.

Whenever new evidence — however thin and debatable — is suggested as an example of where the plague was, we make the same leap in our minds over and over again. A city seems to decline in the mid-sixth century? Must be plague. An economic center suddenly moves elsewhere during the sixth century? That’s plague too. An inscription referring to a few people dying in the same year? Not only is it definitely plague, but it is also evidence for fundamental changes in all aspects of life in that place too. A plague pandemic simply does something because it is, well, The Plague, and that makes it easy for us to attribute causality.

These earth-shaking effects assume that ancient and medieval people were passive victims of a deadly biological agent. Not only was there nothing they could do to avoid death, but they did not even know what was happening to them, since they did not know about bacteria or viruses. Yet we should not assume that people with less medical knowledge must have died in greater numbers everywhere or that this would have inevitably changed the world.

These ideas stem from a problem of scale and sources. As we all know, the ancient world has fewer sources and less data than the 21st century. This absence of material has left a void that is easy to fill with pandemic stories. It does not seem to be an issue to suggest that the plague in the 540s led to the Islamic conquests 90 years later in the 630s. Translating such proposals to the present reveals their implausibility. If you made a similar hypothesis about the initial outbreak of the Third Plague Pandemic (1894) you could argue that it led to the end of the Cold War, for example, or that the 1918 Influenza pandemic led to 9/11 and the Iraq War.

Pandemics, as those over the last few centuries in the modern world have shown, are rarely the sort of grand, epoch-making events that some ancient and medieval historians have portrayed them to be. For example, the Third Plague Pandemic (globalized circa 1890s–1950s) did cause changes in how people worked, lived, and thought, but it did not spell the end of political systems, economic connections, or major cultural upheavals everywhere. Was the impact of a pandemic uniform or variable? While scholarship on ancient pandemics has generally assumed a relatively similar impact across space, evidence from the Third Pandemic reveals a more nuanced picture. Whereas, in India, the plague’s mortality was significant (approximately 12 million deaths), plague killed only a few hundred people in the U.S. across several decades. Effects in other locations around the world — from Australia to Scotland and from South Africa to Brazil — were negligible from a demographic perspective.

The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear, but some combination of socio-cultural and ecological factors were in play. Regardless of whether the Third Pandemic is a better paradigm to understand plague pandemics — a historical argument that may be accepted or rejected — ignoring the question and assuming a uniform impact is misleading.

What, then, can we do next? First, recognize our implicit biases when it comes to hearing the word “plague” in ancient sources. We should question the assumption that a single local source — even evocative and famous ones such as Procopius of Caesarea’s account of plague in Constantinople in 542 — can stand in for any other place that has even a vague possibility of a generic disease outbreak. Second, we need more information. New scientific sources such as ancient DNA or pollen cores are independent of textual evidence, and they can corroborate or refute earlier arguments. As historians we must learn to read those sources — and evaluate their conclusions — critically. Others have already been stepping forward, delving into specific written sources, exploring new genres, and re-thinking old evidence in detail.

At the same time, we must also begin to acknowledge that scientific and medical knowledge today does not necessarily mean better outcomes during pandemics. In the U.S., for example, significant work since the beginning of the century has suggested ways to ameliorate a respiratory pandemic, but political limitations and uninformed decisions have driven many of our choices during Covid, leading to hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths, especially among minority communities and the poor.

Writing about the links between modern and ancient history (as in our AHR article) has also highlighted the power of the recent past to shape the questions we ask about the ancient world. How we write histories of the past will be shaped by our experiences during Covid, just as earlier histories were shaped by the Third Pandemic or HIV/AIDS.

Our work could only explore these questions through dialogue and discussions with colleagues who investigate the histories of science, medicine, and disease over the past couple of centuries. During the Covid Pandemic, we expanded these conversations with the many guests on our podcast, Infectious Historians, who have shared their diverse questions, covering topics ranging from recurring Yellow Fever outbreaks in New Orleans to rat-catching for stopping plague outbreaks in Hanoi. As pre-modern historians, we have a lot to learn from the methodologies our modernist colleagues have developed, so that we can rewrite the histories of disease and pandemics in the ancient world. We hope that the changing academic realities during the Covid pandemic, and the focus it has brought to historical pandemics, will continue to facilitate non-traditional connections across disciplinary and field boundaries.

Header image: Ravenna Mosaic. Image courtesy of Elizabeth Herzfeldt-Kamprath.

Authors