Nina Papathanasopoulou

January 23, 2020

In addition to presenting the latest research on Greco-Roman antiquity and the ancient Mediterranean, attendees at the SCS annual meeting have increasingly had the opportunity to discuss other important issues such as the history of Classics as a field; systemic concerns and directions for the future; and ways to make the field more accessible to people from a variety of backgrounds and experiences. The SCS has recently also incorporated into the annual meeting lectures by influential artists and writers whose work draws on, adapts, and interprets ancient Greek and Roman texts for the broad public. Luis Alfaro, the Chicano playwright and performance artist, spoke about his adaptations of Greek tragedy during the 2019 annual meeting in San Diego, while this year in Washington, D.C., Madeline Miller, writer of best-selling novels Circe (2018) and Song of Achilles (2012), discussed imaginative takes on Homer’s epics. Their contributions to the field indicate the value in seeking out conversations with those who engage with the Greek and Roman worlds outside the Classics classroom.

Eos, an affiliated group of the SCS that focuses on Africana receptions of the Classics, joined in this year’s effort to bring contemporary artists into conversation with the Classics community at the SCS 2020 meeting. This year Eos organized a panel and put together an art exhibition on “Black Classicisms in the Visual Arts.” Their aim was “to trace and interpret visual responses to classical materials among people of African descent and relate them to the typically more text-based study of Black Classicisms.” With support from the SCS and Onassis Foundation USA, Eos arranged that the panel be held not at the conference hotel, but at “Busboys and Poets,” a local events space a few blocks away named in honor of Langston Hughes and known for its social activism and as a gathering place for political and cultural conversations. Six scholars presented papers on various works of visual art, from movies to paintings and sculptures, while Shelley Haley, the SCS President-Elect for 2021 and the Edward North Chair of Classics and Professor of Africana Studies at Hamilton College, gave an introduction and response to the papers.

.jpg)

Alongside the scholarly papers, Eos displayed some of the prizewinners from the juried art exhibition of area artists whose work responds to Greco-Roman antiquity or to the tradition of artists of the African diaspora who have engaged with classical antiquity. Thirteen artists were selected by the jurors: Ahmari Benton, Anne Bouie, Tim Davis, Margery Goldberg, Hubert Jackson, Ibou N’Diaye, Gavin Sewell, Troy Jones, Hampton Olfus, Qrcky, Cynthia Sands, Aïsha Thermidor, and Charles Trott. Nine out of the thirteen artists were present to discuss their work at the end of the panel, and mingled with the crowd during a food and drinks reception that followed.

In speaking with these artists, I wondered what they found inspirational in Greco-Roman antiquity and how they thought their work related to it. What was it like for them to be part of this panel and to mingle with the SCS community? Hubert Jackson, a local D.C. artist and art teacher, whose work Crossing Boundaries of Time and Place was prominently displayed at the entrance of the event space, creates collages that explore human identity and history and blend together sites and events that are meaningful to him. In his work Jackson uses elements of the past, including African symbols, the pyramids in Egypt, and an ancient Greek temple as the background to a contemporary American city. All of these, he explained during his short presentation, have been part of the existence and history of African Americans, and his work honors them by inviting conversations between these cultures and time periods.

The work of Anne Bouie, an artist and historian, suggests that the notion of Classism exists and is explored universally. Her work seeks “to acknowledge the underlying principles that are considered classic forms of style and substances as they express themselves across time, cultures and peoples.” One of her works to be displayed at the exhibition, Hallowed Ground, is, in Bouie’s words “a call to the memory of spiritual forces. It addresses the ‘hidden’ narrative found in oppressive societies.” She explains the significance of the piece further, noting:

The Chiwara is a ritual object representing an antelope, and is used by the Bambara ethnic group in Mali. As farmers of the upper Niger river savanna, the blessing of agriculture is of central importance to Bambara society. Much like the temple of the Vestal virgins and the Oracle at Delphi, secret teachings accompanied the Chiwara to pass on needed knowledge and skills upon which the very survival of the community depended. The chiwara is surrounded by objects that reference life before and during enslavement, and makes the invisible the visible for the viewer’s reflection of its teachings, and to draw from it whatever the person perceives and needs.

Artist Ahmari Benton was also selected for the exhibition. Benton uses Greek and Roman mythology as inspiration for her art and had her piece, Two Truths and a Lie, displayed during the event at “Busboys and Poets.” The work was inspired by the figure of Medusa, who she views as beautiful, yet dangerous and mysterious. “Myths - whether we are consciously or subconsciously subscribing to them - are how we make sense of the world around us. This is a fact and something that we all share. I'm fascinated by the struggle between the denial and the acceptance of myths on a personal level,” Ahmari commented.

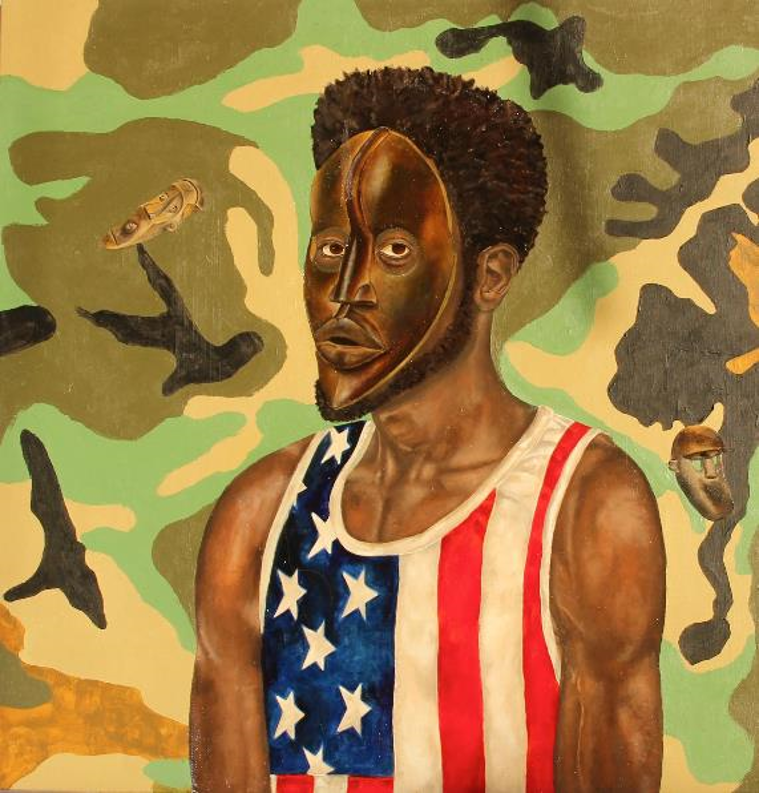

Troy Jones, an African-American artist from New Jersey, creates art that focuses on the identity of African Americans. His paintings follow the style of Caravaggio and portray black men who are wearing a kind of mask. “It is rough for black men in the US”, Jones said. “As a black man, it is difficult to be your true self; you always have to put on a show, to wear a mask.” The ancient Greeks voluntarily donned masks in order to perform roles during festivals, in a ritual affirmation of their larger community. However, Jones’ art portrays black men as compelled to put on a mask; so often and for so long that it becomes a part of their own personal identity.

Tim Davis, an art educator originally from Chicago who currently works with a gallery in D.C. also creates art that reflects on the identity of black men in the US today. His work, Blue Brothers, is according to Davis “a piece about today’s black men who are coming of age, who are working to become stronger and more focused on their heritage and culture.” The lack of facial features on the persons depicted draws our attention to the hair. “For black culture, hair has often been a way of artistic expression and of making a powerful statement,” Davis explained. Studying Greek and Roman sculptures and vase paintings, Davis was fascinated with the emphasis the Greeks and Romans placed on hairstyles and was inspired to do the same.

Artist Charles Trott tries to turn our focus away from appearances and the aesthetic differences that divide us, and centers on the elements that bring us together. As inspiration for his art, Trott uses images from antiquity and often uses maps to help us identify what he is portraying. The Greeks and Romans were highly influenced by Egyptian culture and he wants to bring out that connection in his work. He also wants to highlight the connections between the African world and the Americas.

Hampton Olfus’ art also tries to bring forth the connections between Africa and the Greco-Roman worlds. His work highlights societal roles and customs that pervade many cultures regardless of time and location. Politics, War, and Peace, one of his works selected for the Black Classicisms exhibition, underlines the human tendency towards war and political strife. The work evokes the Trojan War, with Helen as its object standing on the side. “This lady represents the role that women have been pushed into; she is in the background, fragile and scared, while the men are portrayed as the defenders of virtue and justice. It is society that mandates these labels,” Olfus said.

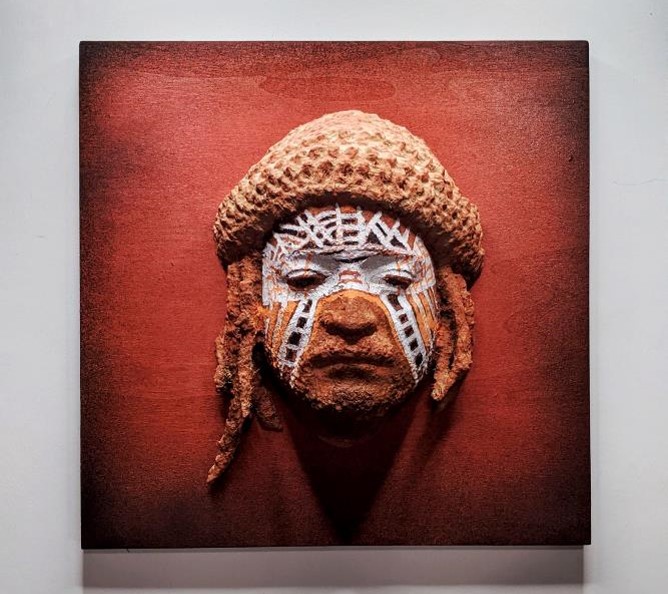

Local artist Qrcky finds Greek and Roman sculptures beautiful and fascinating, but their perfection makes him wonder: why is everyone so idealized, never missing a body part, never with an imperfection? In his own sculptures, Qrcky wanted to fill that gap. “I would have loved to make a black person in marble,” he said. His work titled The Poet is made of PLA plastic and portrays an actual poet, a young black man that he saw perform. His poet wears a knitted cap and his face is partly hidden by some sort of mask. “This mask is hiding him from the rest of the world,” Qrcky explained, “it’s a person who’s never going to be seen.”

Margery Goldberg, a wood sculptor, submitted her art to be part of the exhibition because she considers it “pancultural, related to all cultures and representing all people.” Inspired by the figurative art of the Greeks and the Egyptians, she does primarily figurative sculptures and uses ancient elements, like hieroglyphics in her art. In her sculpture entitled He She Tree the woman and man, carved on mahogany and walnut wood respectively, seem to be coming out of a tree stump. The tree stump, Goldberg pointed out, is like a human torso. The tree offers life, but also stability and strength.

In planning the Black Classicisms panel and exhibition Eos aimed to bring scholarly work on Africana receptions of the Classics in conversation with contemporary artists who are also interested in the Greco-Roman past. Mathias Hanses, Assistant Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies at Penn State and one of the co-founders of Eos, noted that in the study of the ancient world, texts are increasingly put in conversation with the visual arts and the material record. In Classical Reception Studies, the focus lies more than ever on people of color and their creative and scholarly engagements with the ancient Mediterranean. For the panel, he wanted to combine these two scholarly trends. For the whole event, his goal was to see whether and how contemporary artists would use common methodologies and engage with similar issues as the scholarly papers and to learn how their art can inform our understanding of the past, present, and future of Classical Studies. For Caroline Stark, Associate Professor of Classics at Howard University and another co-founder of Eos, the art exhibition instantiates the rich tradition and ongoing vitality of Black Classicism in the Visual Arts and in particular, the importance and influence of Africa in classical antiquity. “Conversing with the artists and engaging with their artworks enriches our understanding of the ancient world and provides another lens with which to view our own work,” Stark noted. Together, these works all illustrate a desire to acknowledge the influence of African cultures on Greco-Roman thought; an interest in portraying the commonalities in African and Greco-Roman beliefs; and a need to think about the past as a guide for the present and future.

The Black Classicisms in the Visual Arts exhibition opens to the public at the Interdisciplinary Research Building (IRB) of Howard University in late January and will run through the end of June.

This event was made possible with the generous support of the Onassis Foundation USA. Eos would also like to thank those who helped organize the event: Helen Cullyer and Cherane Ali at the SCS; Melvin and Juanita Hardy of Millennium Arts Salon; Brandy Jackson, Ashley Bethel, and Carol Rhodes Dyson at Busboys and Poets; Zoie Lafis and the Center for Hellenic Studies; and the panelists Sam Agbamu, Stefani Echeverria-Fenn, Margaret Day Elsner, Shelley Haley, Tom Hawkins, Stuart McManus, and Michele Valerie Ronnick.

Header Image: Marble head of an African child, Roman, 150-200 CE, marble, Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA (Getty Open Content Program).

Authors