T. H. M. Gellar-Goad

January 10, 2014

In last month’s column, I offered an overview of the Greek myth of the Titanomachy, the war between the Olympian gods (Zeus, Hera, and all the rest) and the earlier generation, the Titans; and I discussed some recent media telling of the escape of the Titans from their underworld prison and a second Titanomachy: in Disney’s 1997 Hercules, in the 1998 straight-to-video Hercules and Xena animated movie, in the 2012 movie Wrath of the Titans (sequel to the remake of Clash of the Titans), in the 2013 movie Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters, in the 2011 movie Immortals, and in the video game series God of War.

Today I finish the journey by exploring the ramifications of these stories and their thematic material.

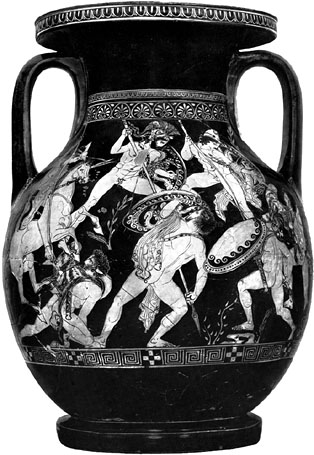

There’s a pattern to these stories. In all of them, the Titans are reawakened and they are opposed by a half-god protagonist: Perseus, Hercules, Percy, Theseus, Kratos (sort of). In each, the protagonist has a history of family loss. Perseus in Wrath of the Titans is a widower. The Disney Hercules is estranged from his birth parents, while the Kevin Sorbo version lost his wife and children to a fireball sent by Hera. Percy Jackson feels abandoned by his father Poseidon. Theseus in Immortals endures the death of his mother during the film. Kratos accidentally killed his family and is killed by his own father. Most of the protagonists are soldiers — Percy Jackson, for instance, is a teenager at a “camp” filled with what are essentially child/teen demigod soldiers. The Titans themselves are generally either monstrous or demonic in appearance, in contrast to the ancient Greek depictions of them as essentially anthropomorphic (as in the vase painting to the right).

So what’s the meaning behind all these modern Titanomachies? The surface explanation — that gods fighting gods makes for cool action scenes — isn’t all there is to it.

A basic element in both the original Titanomachy and these motion-picture reimaginings is generational conflict and change. The Olympians’ victory over the Titans represents the passage of power from parent to child, and the battle may represent the intra-familial and whole-society power struggles that mark the transition. From an American political perspective, the 1990s Hercules movies came out during the administration of Bill Clinton, the first president born after World War II and the first since then not to have served in the military, while the more recent Titanomachy films have been produced during the first post-Baby Boomer presidency.

Moreover, the Titanomachies we’re talking about focalize the conflict through a third generation, the half-mortal age that will presumably inherit the earth from the Olympians. Linked to this focal point is the fact that in all of my examples, the Olympians are portrayed as weak and flawed — whether it’s mere absenteeism (Disney; Percy Jackson), powerlessness or cowardice (Disney; Hercules and Xena), treacherous cruelty (Hercules and Xena; God of War), or even mortality (Wrath of the Titans; Immortals; God of War). The concept of the death of the gods fits well with the current moviemaking trend of demystifying our heroes, just like the grim Superman of the 2013 Man of Steel, the gratuitous violence and abusive sexuality of the HBO series Rome and Game of Thrones, and even the reduction of the Minotaur of Immortals to a bodybuilder with a bull helmet. The death of the gods — who are themselves shown to be corrupt — can also symbolize the fact that we, the current generation of humankind, must deal with the “sins of the father” we have inherited from our forebears.

Moreover, the Titanomachies we’re talking about focalize the conflict through a third generation, the half-mortal age that will presumably inherit the earth from the Olympians. Linked to this focal point is the fact that in all of my examples, the Olympians are portrayed as weak and flawed — whether it’s mere absenteeism (Disney; Percy Jackson), powerlessness or cowardice (Disney; Hercules and Xena), treacherous cruelty (Hercules and Xena; God of War), or even mortality (Wrath of the Titans; Immortals; God of War). The concept of the death of the gods fits well with the current moviemaking trend of demystifying our heroes, just like the grim Superman of the 2013 Man of Steel, the gratuitous violence and abusive sexuality of the HBO series Rome and Game of Thrones, and even the reduction of the Minotaur of Immortals to a bodybuilder with a bull helmet. The death of the gods — who are themselves shown to be corrupt — can also symbolize the fact that we, the current generation of humankind, must deal with the “sins of the father” we have inherited from our forebears.

In Terry Castle’s view, the lesson of the (original) Titanomachy is “that individual human beings are endowed with critical faculties and powers of moral discernment, and as a result, have a right, if not the obligation, to challenge oppressive, unjust, and degrading patterns of authority,” particularly parental authority. Applied to the Titanomachic sequels that have captured American storytellers’ imagination, Castle’s reading might suggest a growing lack of confidence in those very critical and moral capabilities that have led us to challenge the status quo.

The fact that these gods-against-Titans battles are second Titanomachies in particular underscores also an ongoing anxiety about enemies imprisoned. Most of these stories postdate the establishment of the American prison at Guantánamo Bay and the larger issues of terrorism, prisoners of war, and national security that it entails. (American anxiety about how to deal with global, grassroots enemies predates Guantánamo and September 11th; and both the Xena TV series and the Disney Hercules spinoff series have episodes involving Titans getting free and wreaking havoc.) Unlike Hesiod’s Titans, not all of America’s enemies can be met on an open battlefield or sequestered securely underground — and unlike Hesiod’s Titanomachy, the real-life modern struggle is neither simply two-sided nor merely black-and-white.

Another element of what is going on here is environmental: in the Disney Hercules movie, and in the Hercules and Xena movie, the Titans are elemental beings, monsters formed out of and possessing power over natural forces like fire or water or earth. Similarly, Kronos in both Wrath of the Titans and Percy Jackson is a giant fire monster. Part of what we do as human beings is try to control the natural world — try to gain power over it. We are not always successful, and our attempts to contain natural forces can come back to threaten our safety or even our entire way of life. I’m not quite ready to suggest that Wrath of the Titans is an advocacy piece on global warming, but I do view that as one of the reasons for the appeal of stories involving Titans depicted as elementals. In Immortals, the Titans are not elementals but instead are basically like orcs from the Lord of the Rings movies; it’s worth recalling, then, how the villains in Lord of the Rings were depicted destroying the landscape in the name of the industry of war.

Finally, I think that the rehashing of the Titanomachy can represent our struggle with our own inner demons. The imprisonment of the Titans is the suppression of primal emotions, or the violence within ourselves (the “return of the repressed” of Freud or the “shadow” of Jung), and the flawed Olympians reflect the corrupting effect of not dealing with those dark parts of our mind. In contrast with the ancient Greek model, the modern Titanomachy places the battle between the psychological Titan and Olympian squarely in the hands of the humans, the earthbound protagonists: in our time, it seems, whether the struggle is psychological, environmental, political, or generational, it is up to us, and us alone.