Thomas Hendrickson

February 15, 2022

The Cambridge Greek Lexicon (CGL) set out to replace the Middle Liddell, a goal whose overwhelming success cannot be in doubt. Indeed, it puts the field of classical studies in the awkward position of having a student dictionary that is on sounder footing than its chief scholarly dictionary, and it seems likely that CGL will be the go-to resource not just for undergraduates but for grad students and scholars when reading classical Greek literature.

Yet the words “classical” and “literature” in the previous sentence carry a good deal of weight. In order for the dictionary to be completed in a reasonable amount of time, and at a size and cost that will be manageable for students, CGL excluded quite a bit of material. Its coverage “extends from Homer to the early second century AD (ending with Plutarch’s Lives)” (CGL 1: vii), but it covers this material selectively, and the focus is clearly on poetry from Homer to the Hellenistic period and on literary prose down to Aristotle. There is very little coverage of Roman-era works, religious works, technical works, and documentary works.

A dictionary made from new readings and intended for students will necessarily have to limit itself in scope. All the same, the decisions about inclusion and exclusion are consequential, and seem to reflect an outdated vision of classical studies that is rigidly bounded by disciplinary borders.

Overview of Greek dictionaries

The dictionary now known as “Liddell and Scott” was published in 1843 as A Greek-English Lexicon Based on the German Work of Francis Passow. Franz Passow’s 1819–1824 Handwörterbuch der griechischen Sprache was a revision of Johann Gottlob Schneider’s Kritisches griechisch-deutsches Handwörterbuch (1797–1798), which itself drew much material from Stephanus’s 1572 Thesaurus Graecae Linguae. The Liddell and Scott lexicon was substantially revised in its 9th edition (1929–1940) by Jones and McKenzie, with a supplement revised in 1996. The “Big Liddell” is also, after the 9th edition, called the “LSJ,” reflecting the work of Jones, though not McKenzie. A searchable version is available free online.

There are two smaller versions of Liddell and Scott, both of which were abridged from editions prior to the major overhaul done by Jones and McKenzie: the Little Liddell, first published along with the full version in 1843 but with minor revisions as late as 1871, and the Middle Liddell, published in 1889 as an abridgement of the seventh edition (1882). A searchable version is available free online.

A second scholarly dictionary in English came out in 2015: The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (ed. Montanari). The Brill dictionary is a translation of Montanari’s Vocabulario della lingua greca (3rd ed. 2013), which updated and built on Rocci’s Vocabulario greco-italiano, whose third edition (1943) drew heavily on the LSJ. So, while the Brill dictionary does offer many real improvements on the LSJ, it also shares some of its same problems and limitations. (For more details on these problems, see John Lee’s review of the Brill dictionary.)

A third scholarly dictionary, unlike the others in its scale and ambition, is currently in progress. The Diccionario del Griego-Español, edited by Francisco Rodriguez Adrados, is an attempt to comprehensively include every usage of every Greek word from Mycenaean times to AD 600 (available here free online). Begun in 1980, it is currently a portion of the way through the letter Ε.

Background on the Cambridge Greek Lexicon

The initial goal of CGL was to update and revise the Middle Liddell. The language of the English definitions in the Middle Liddell, reflecting usage and attitudes from Victorian times, could be difficult, misleading, or obscure; James Diggle, the chief editor of CGL for the last 15 years, pointed out examples like χέζω as “to ease oneself” and λαικάζω as “to wench,” to which we might add κίναιδος as “a lewd fellow.” Beyond that, the Middle Liddell had missed out on Jones and McKenzie’s revision, which made it terribly out of date. Even the big revision of Jones and McKenzie left numerous flaws, as John Chadwick detailed in “The Case for Replacing Liddell and Scott” and in Lexicographica Graeca; these works served as a kind of manifesto for CGL, which Chadwick proposed in 1997.

The editors soon decided that the Middle Liddell was beyond redemption: they would need to rewrite every entry based on fresh readings. This would mean not revising the Middle Liddell, but replacing it entirely. (Diggle details the history here, starting just before 4:00.) In a different era, this would have entailed the laborious gathering of hundreds of thousands of examples of word-usage on index cards, a process that can take generations. (The Thesaurus Linguae Latinae, started in 1890, hopes to be finished by 2050; the Diccionario del Griego-Español does not seem likely to beat that pace.) Luckily for us all, resources like the Perseus Project and the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae allow instantaneous corpus searches, which speeds the timeline considerably.

The goal was not just to modernize the definitions, fix errors, and create a more readable format. Editors also wanted to take a more lexicographically modern approach: for instance, starting an entry with the word’s root meaning rather than its earliest attestation, and carefully distinguishing between a definition and a translation. Entries would still include notice of which authors used each sense of the word, but quotations would be excluded, since they are easily searchable elsewhere. Longer entries would start with a roadmap to clarify at a glance the history of the word and the inter-relationships of its various senses. Diggle outlines the chief features of the new dictionary here (starting at 12:00).

Both price and size are at the upper limit of what students might be able to bear. The dictionary is 1,529 pages, spread over two volumes, and retails for $85 new — though the circulation of used copies will eventually make cheaper copies available. This is larger and more expensive than the Middle Liddell (910 pages, $60 new/$25 used) but smaller and cheaper than the Big Liddell (2,300 pages, $220 new/$150 used). Yet most students probably just use the free versions of these dictionaries on their phones through Logeion or the like. (And if they don’t, they should!) The CGL is not yet available in a digital format, but the decisions they make about price and platform will be tremendously consequential.

Words, words, words: λόγος in various Greek Dictionaries

To give a sense of the consequences of the various changes outlined in the previous section, let’s consider the word logos.

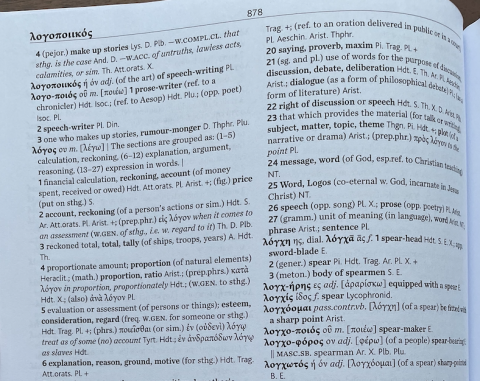

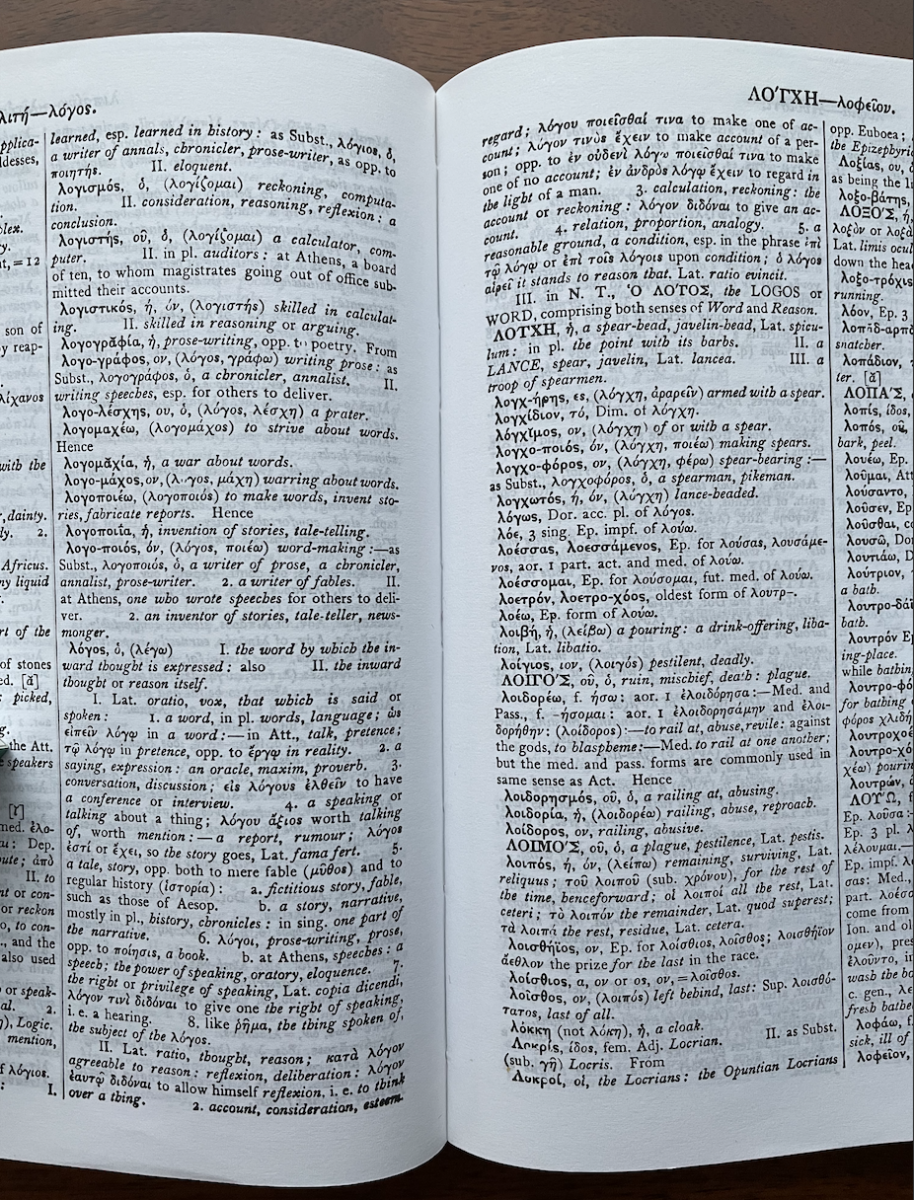

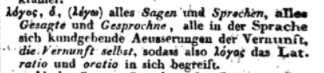

The Little Liddell and Middle Liddell both start their entries with two basic meanings, “word” and “thought,” which are defined in English but in Latin as well: oratio and ratio.

Figure 1: The entry for logos in the Little Liddle. Photo courtesy of the author.

Figure 2: The entry for logos in the Middle Liddle. Photo courtesy of the author.

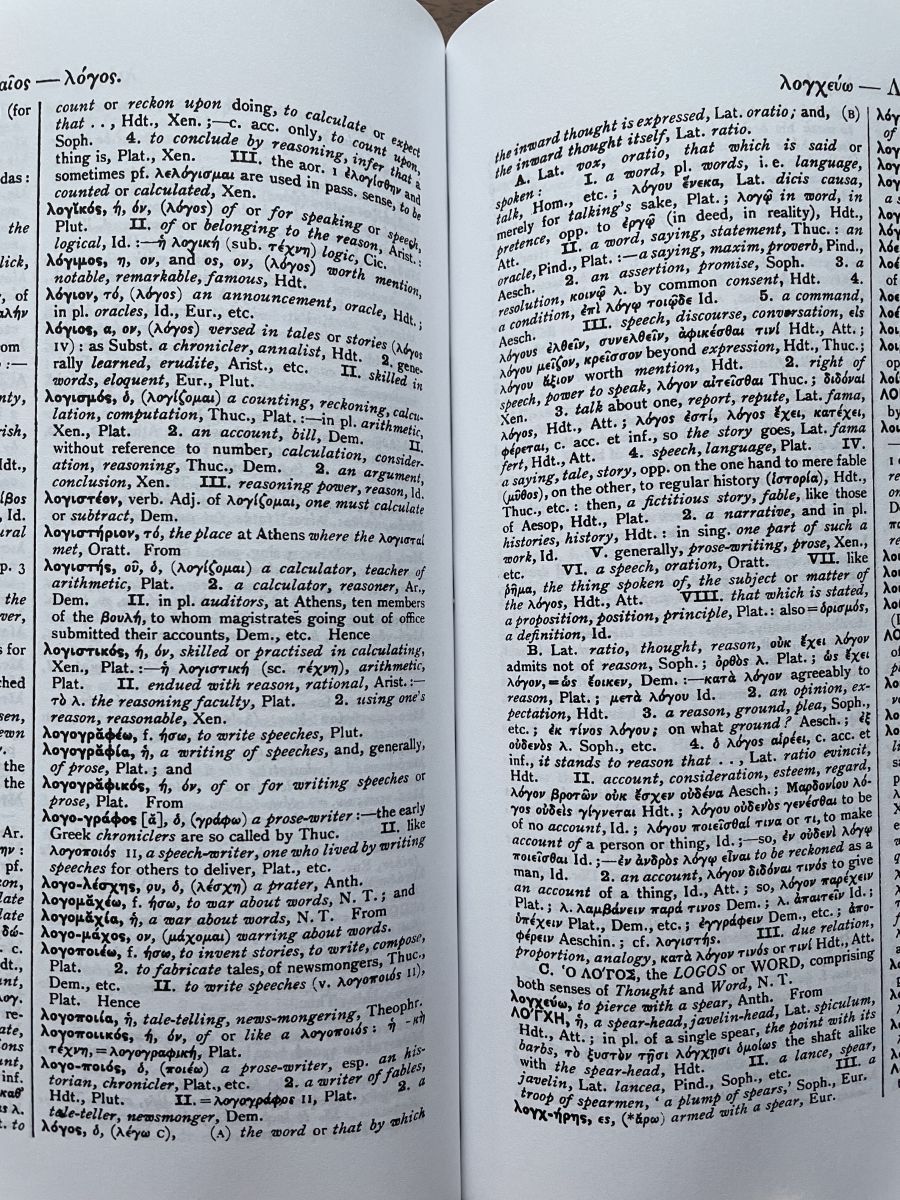

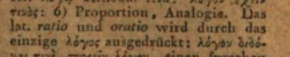

The wordplay goes back to Schneider’s 1797 Handwörterbuch, though it was Passow who made the ratio/oratio distinction into an organizing principle in his 1819 revision.

Figure 3: The entry for logos in Schneider's Handwörterbuch. Photo courtesy of the author.

Figure 4: The entry for logos in Passow's revised Handwörterbuch. Photo courtesy of the author.

I’m no lexicographer, but I strongly suspect that Latin wordplay is no longer considered a sound tool for dividing up the meanings of a Greek word. In any case, both Little and Middle Liddell also add a third division for the word: “the LOGOS or WORD, comprising both senses of Thought and Word, N.T.” This definition notes a distinct Christian meaning for logos, though it does not explain what makes it distinct or different.

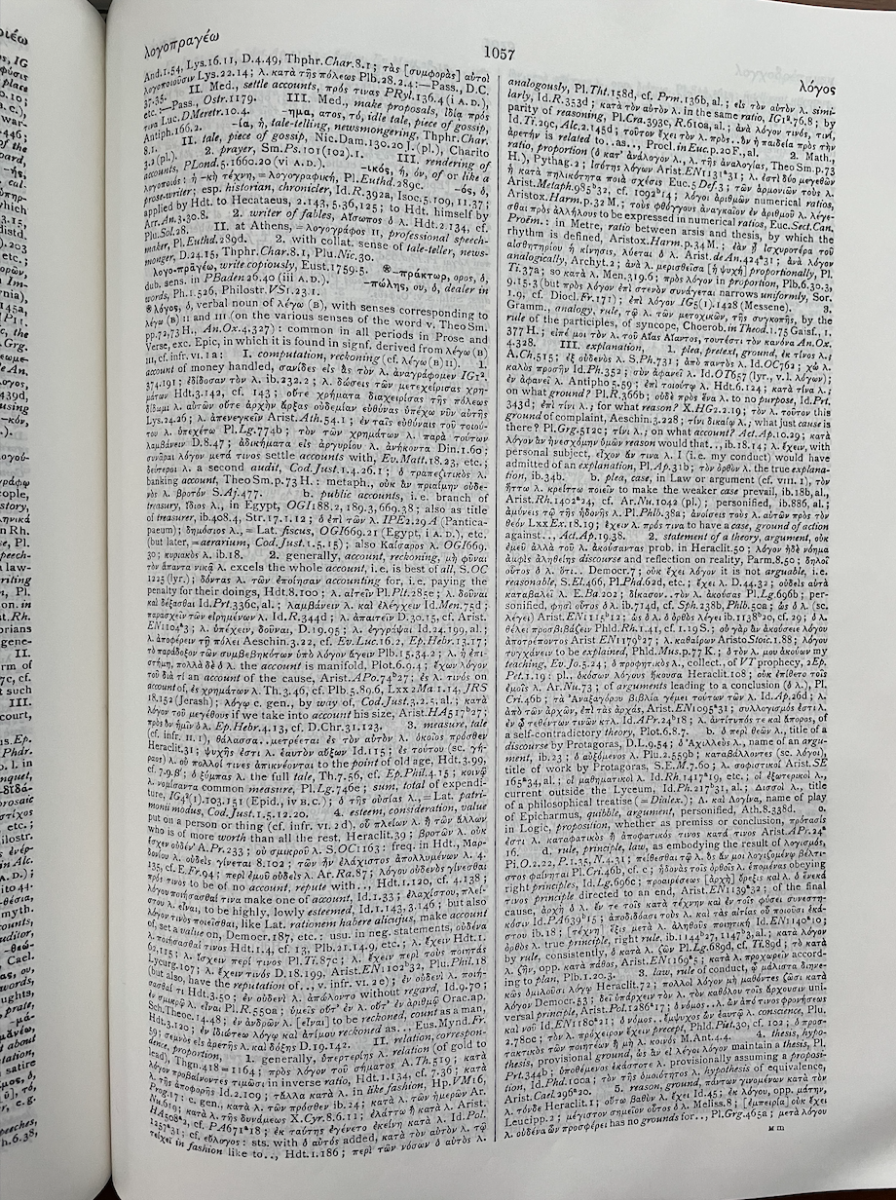

The LSJ entry for logos is much sounder and more nuanced, though the length probably makes it difficult for students, and the format makes it difficult for everyone. It comprises ten distinct definitions, covering about five and a half columns of text, over three large pages.

Figure 5: The first page of the entry for logos in the LSJ. Photo courtesy of the author.

Each of these definitions has various sub-definitions and sub-sub-definitions. These hierarchies are helpful for understanding how the meanings progress, but they are very difficult to follow because they are grouped in unbroken blocks of text, mingled in with a mass of quotations. Denniston once wrote that “the reader should be enabled to bathe in examples” (Particles vi); a student reading the LSJ might well drown in them.

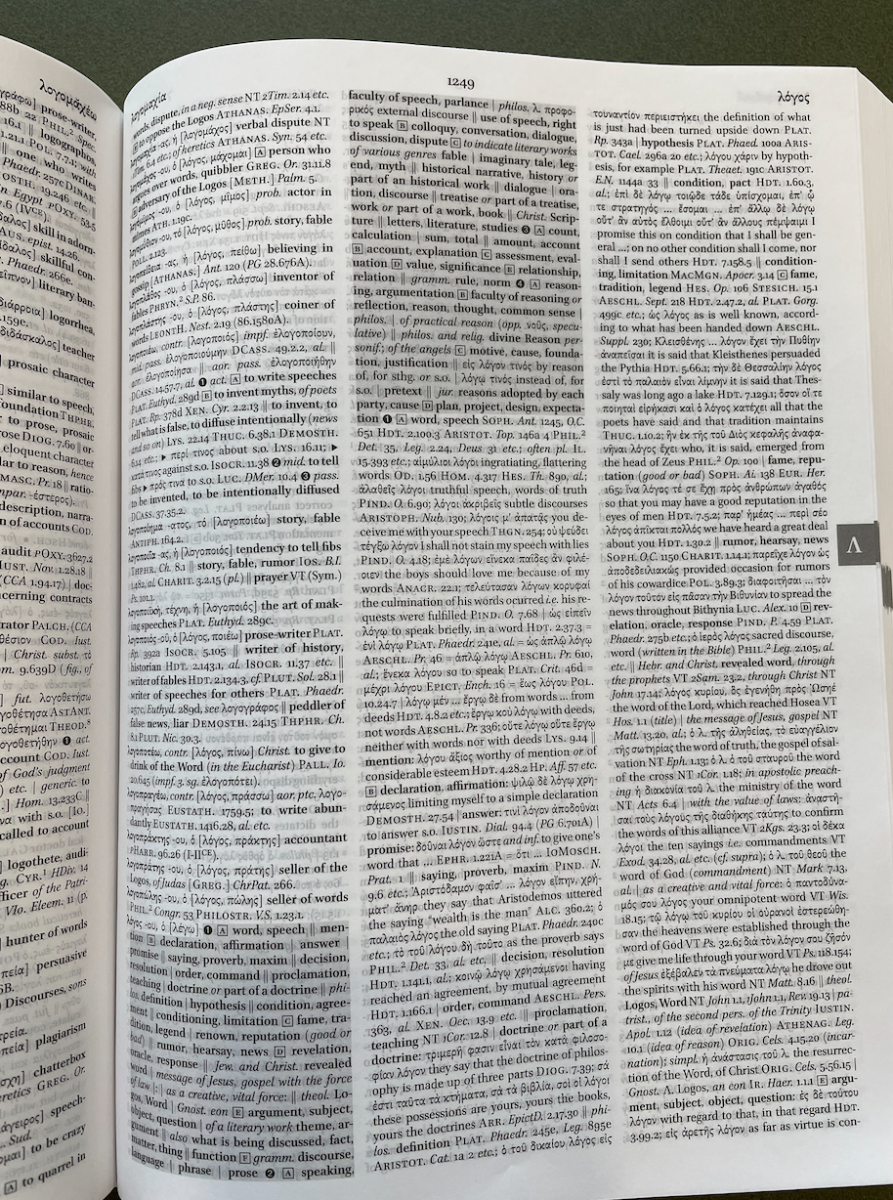

The Brill dictionary’s entry for logos is vastly easier to read, both because of general formatting improvements and because of the presence of a roadmap at the start of the article.

Figure 6: The first page of the entry for logos in the Brill dictionary. Photo courtesy of the author.

The Brill dictionary does include quotations, and the article is broken into four primary definitions (each with sub-definitions) that stretch across six columns over about two large pages. Curiously, while the LSJ starts with a primary meaning of “computation” and gradually reaches the meaning “speech,” the Brill dictionary starts with “speech” and gradually reaches “computation.” I do not understand Brill’s rationale on this ordering, since the noun logos comes from the verb legō, and Brill agrees with the LSJ in portraying the senses of legō as unfolding from “pick,” to “compute,” to “enumerate/speak.”

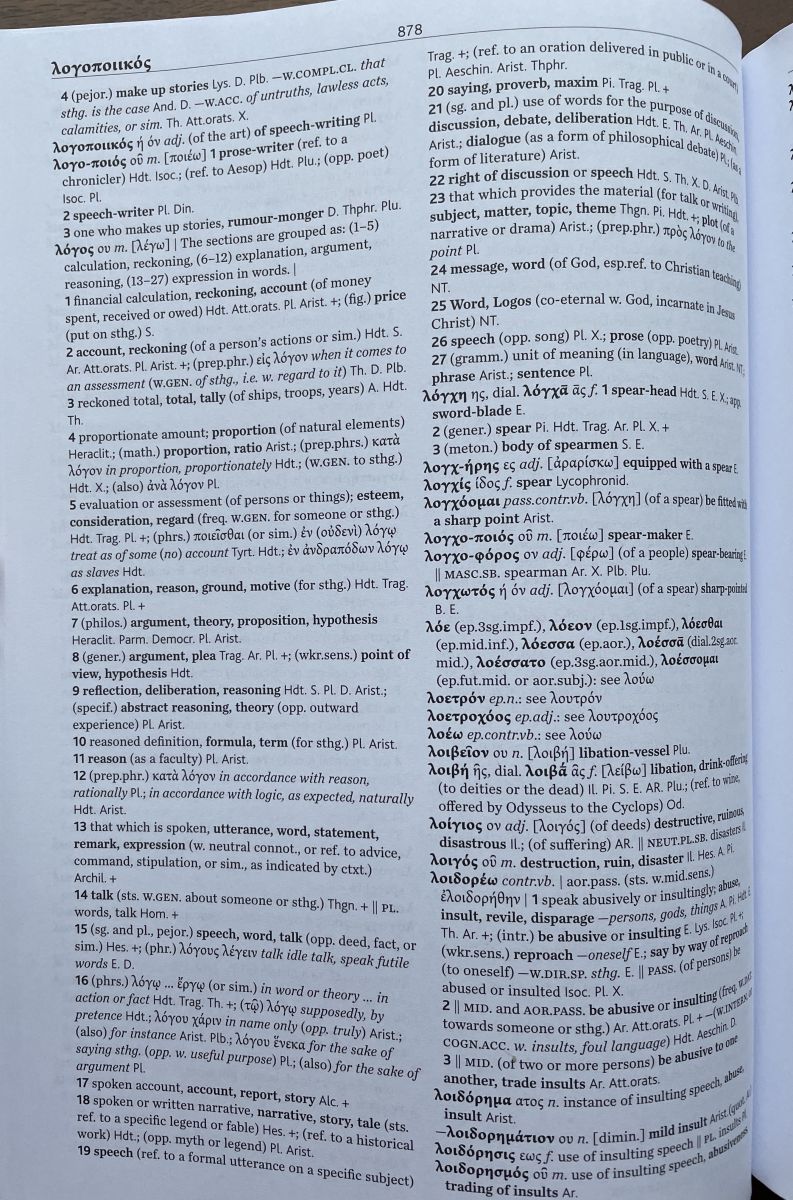

CGL has 27 distinct definitions in two columns on a single page.

Figure 7: The first page of the entry for logos in the Cambridge Greek Lexicon. Photo courtesy of the author.

The formatting and roadmap at the start of the article make even 27 definitions easy enough to follow. The high number of definitions seems likely to be the consequence of promoting many meanings that were sub-definitions in the LSJ. CGL apparently does not use sub-definitions, and uses the order of the definitions, and the roadmap, to show the relationships between the various meanings. The meanings offered do not differ radically from the LSJ and follow the same general progression, but the entry is radically easier to read.

The logic of inclusion and exclusion in the Cambridge Greek Lexicon

The speedy creation of CGL in just 23 years was made possible by new technology, but also by the editorial decision to limit the selection of texts whose readings would be considered. The corpus of ancient Greek is vast, no matter what one’s definition of “ancient” is. It’s no surprise that the Diccionario del Griego-Español has managed to get through about one letter of the Greek alphabet per decade. The limitation of texts was also necessary to keep CGL itself at a usable size. As it is, the work takes up 1,529 pages across two volumes.

CGL covers works that extend from Homer to Plutarch. Yet, within this period, not all texts are included. The exclusions, while necessary, are significant and consequential. Indeed, given that a dictionary is one of the most essential tools in the field of language study, the material included and excluded provides a vision of the field as it is (or as the editors understand it to be), but also a prescription for the field as it goes forward.

A glance at the list of authors and works treated (CGL 1: xv–xix) shows that the focus has been placed on classical Greek literary works: literary prose from the origins to Aristotle and poetry from the origins to the Hellenistic era, including quite a few fragmentary poets.

So, what gets left out of CGL?

Works from the Greek-speaking world’s two largest surviving religious traditions, Judaism and Christianity, are largely excluded. Works by Jewish authors are excluded entirely, though the period from Homer to Plutarch would encompass the Septuagint, 1–4 Maccabees, pseudo-Aristeas, Philo of Alexandria, and Josephus. The four canonical Gospels and Acts of the Apostles are included, but all other texts from the Greek Bible are excluded, as is other early Christian material such as the Didache.

CGL excludes most prose after Aristotle, and even Aristotle is not covered in his entirety. Polybius is included, but other historians do not make the cut (e.g., Diodorus Siculus, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Josephus, Appian, fragmentary historians, Plutarch’s Caesars). The Characters of Theophrastus is included, but most other post-Aristotelian philosophy is left out (e.g., the rest of Theophrastus, other Peripatetics, Philodemus, Epictetus, fragmentary philosophers). Dio Chrysostom and Plutarch’s Moralia are excluded, as are technical writers in fields such as medicine (the Hippocratic corpus), natural philosophy (Aristotle), geography (Strabo), mathematics (Euclid), mythography (Parthenius of Nicaea), grammar (Dionysius Thrax), and literary criticism (Longinus).

CGL also excludes most inscriptions and papyri, although it does include some poetic fragments and Aristotle’s Athenaeon Politeia.

The cutoff with Plutarch, which is somewhat arbitrary, also leaves out other commonly read authors from the second century, such as Lucian, Longus, Achilles Tatius, Galen, Pausanias, and Marcus Aurelius.

I want to emphasize again the necessity of exclusion. For a dictionary created from new readings, of this size, and completed within our lifetime, it would have been flatly impossible to include all the works listed above. Incorporating even a few of these authors might well have added years to the process and created an oversized product crowded with rare definitions that a student is unlikely to encounter. After all, this dictionary is “designed primarily to meet the needs of modern students” (CGL 1: vii), and it’s the rare student who winds up in a class on Parthenius of Nicaea.

At the same time, it’s necessary to acknowledge the consequences of these exclusions. After all, “modern students” really do read Lucian, Longus, and Achilles Tatius, all of whom are popular enough to have Green & Yellow editions. The Greek Bible (beyond Gospels and Acts) is regularly taught in just about every school with a Greek program, at least in the US.

These exclusions have a bearing on the dictionary’s usefulness even for the works that are covered. For instance, a student reading Gospel of John might open CGL and find the following entry for logos: “Word, Logos (co-eternal w. God, incarnate in Jesus Christ) NT.” The meaning of logos as the Word of God occurs in the Septuagint, Philo, and the Corpus Hermeticum (see LSJ logos, definition X), but a student reading the CGL entry might well think of it as a uniquely Christian notion rather than one arising from Christianity’s Jewish context.

It might be the case that CGL rightly focused on the traditional canon of major classical authors, given that it had to be highly selective. And to be fair, the editors initially attempted to include “Strabo, Galen, Hippocrates, Lucian, the Greek Anthology, and the scientific works of Aristotle and Theophrastus,” only to find them impractical. At the same time, the logic of the ultimate selection results in a tool that hasn’t quite caught up with “modern students,” many of whom find technical and sub-literary texts of great interest, who do not view Roman-era Greek works as inherently inferior, and who see Judaism and Christianity as a part of the diverse religious landscape of the Greek-speaking world rather than as distinct phenomena to be studied through the lens of their subsequent histories.

Hendrickson would like to thank Raphael Esquivel and Zoe Jovanović, from his Taking Literature Apart course, for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Authors