Michele Ronnick and Kirk Ormand

August 8, 2019

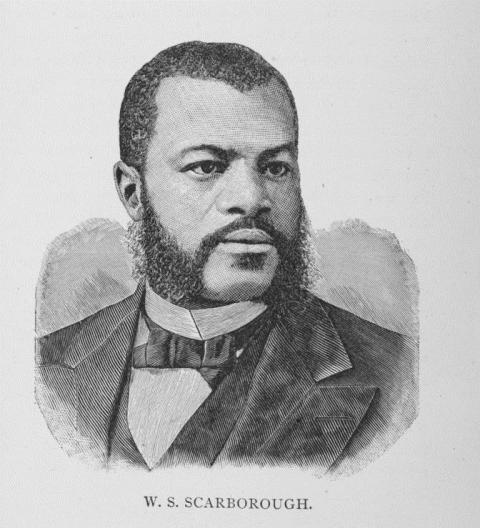

Williams Sanders Scarborough, an 1875 graduate of Oberlin College, was a pioneering African American scholar who wrote a university-level Greek textbook. Kirk Ormand, who now teaches at Oberlin, interviewed Prof. Michele Ronnick, who has recently published a facsimile edition of Scarborough’s Greek textbook, First Lessons in Greek (1881), with Bolchazy-Carducci press. Prof. Ronnick is the world’s leading expert on Scarborough. She found, edited, and published Scarborough’s autobiography in 2005, and has researched Scarborough’s time at Oberlin and as President of Wilberforce University.[1]

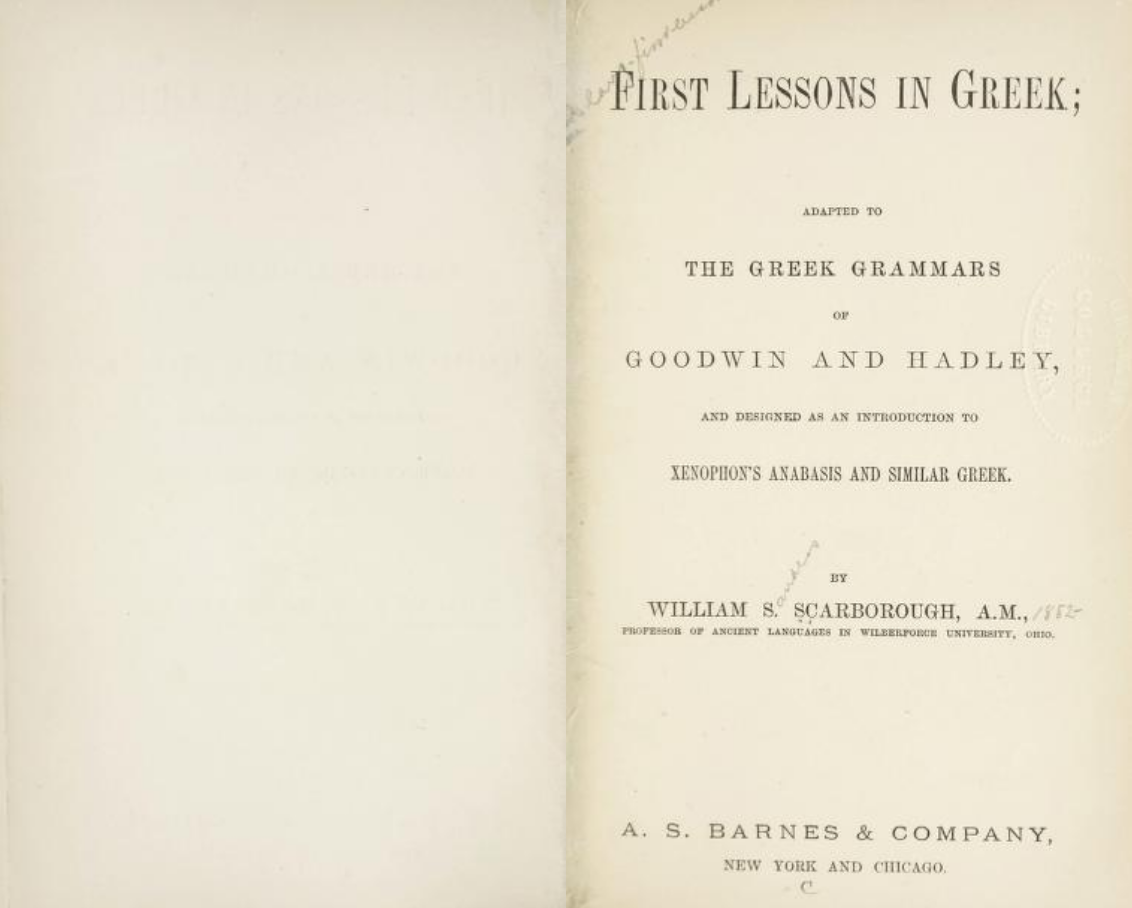

Kirk Ormand: You are publishing a facsimile edition of William Sanders Scarborough’s First Lessons in Greek.Tell us a bit about why Scarborough’s book is important to the history of the profession.

Michele Ronnick: Scarborough was a former slave, and his life could have been limited to manual labor – fixing shoes or doing some sort of menial job. So the very fact that he overleaped this apparent destiny and made himself into a learned man draws our admiration. Americans of that era believed, as David Hume did, that African American people weren’t intelligent enough to grasp Greek and Latin. The idea is summed up in a quote attributed to John C. Calhoun and overheard by black clergyman Alexander Crummell, who had studied Greek at Cambridge: “If you can show me a Negro who understands the Greek syntax, I will believe that the Negro has a soul.”

This embodied the sentiment of the time. Scholar and activist Anna Julia Cooper (Oberlin Class of 1884, MA 1887) knew the quote, and professor and attorney Richard Greener, the first black member of the American Philological Association and the first black graduate of Harvard knew it. He reminded Scarborough of it when he exhorted him to write his Greek textbook, to “Keep at your work.” So the book is material proof of Scarborough’s abilities and ambitions, and he knows that it has political implications. He stands up and vindicates his learning as a man, his ability and his intellect, and then throws down the gauntlet to say, “this is a pathway for us, too.”

A Voice from the South (Image is in the Public Domain and via Wikimedia).

The other important reason for the facsimile edition of his book is its rarity. There are less than 10 copies left in the world owned by certain institutional libraries. The Oberlin College Archives has one. The Library of Congress has one. Wilberforce has one. Howard University has one, and Frederick Douglass’s personal library at his home in Anacostia has a signed copy because they were friends.

The textbook is also part of the African American drive to engage in pedagogy and write their own textbooks. Scarborough is actually the first person of African American descent to write a language textbook. It was a typical book for its time, but written by a very atypical author. The book made him famous. It’s one of the things mentioned in his obituary in the New York Times on September 12, 1926, and that he was the first member of his race to create a Greek textbook suitable for university and college use.

KO: How did you first get interested in Scarborough?

MR: I read a brief biographical sketch of Scarborough’s life in The Dictionary of American Negro Biography, eds. Rayford Logan and Michael Winston (Norton, 1982). My training at Boston University with Professor [Meyer] Reinhold revealed the deep roots of the classical tradition among white people, but it quickly became clear to me that classicists had not thought to examine the place of classical studies in the history of African American education. So, I read that whole dictionary, and anywhere it mentioned Latin or Greek or classics, I made note. This became my starting point. But the short biography of Scarborough was extremely intriguing because it said he had written an autobiography and had published a Greek textbook in 1881. I was determined to find those books. As I was looking, I found an article by Dr. Arthur Stokes, “Historical Justification for Scarborough,” in the A.M.E. Church Review that argued that the three leading African American intellectual forces coming out of the 19th century were [Frederick] Douglass, [Booker T.] Washington, and Scarborough. That caught my attention – I began to realize that Scarborough was a giant whom we had forgotten.

KO: So you tracked down an unpublished manuscript of Scarborough’s autobiography and published it – remind me when that came out?

MR: The Autobiography of William Sanders Scarborough: An American Journey from Slavery to Scholarship, with a forward by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., came out in 2005 with Wayne State University Press. The APA (now the Society for Classical Studies) gave it and my photo installation, 12 Black Classicists, funded by the James Loeb Classical Library Foundation, its Outreach Award in 2007.

The autobiography was a thrilling discovery. A copy of it was supposed to be at Wilberforce, but it wasn’t. I was told that the F-5 tornado that tore through Wilberforce in 1974, ripping the university’s library roof off, had probably destroyed it. But luckily there was a typed copy, and after a long period of sleuthing I found it – not the original, of course, but a 368-page cradle-to-grave account of Scarborough’s life and a primary witness to American history. It was a self-portrait of his emergence from slavery and his wish to be a learned person, a scholar. But Scarborough became more than a scholar. He was a leader of the Republican party for decades and president of Wilberforce University for 12 years and through the tumult of WWI. I doubt he thought he’d be visiting troops or comforting broken soldiers (and his former students) coming back to Jim Crow America, those who were thrown off buses and trains when they returned, but that was part of his story too. When I got through reading the autobiography, I was astonished by the range and extent of his work.

KO: Tell me a bit about Scarborough’s place in the history of are profession. What should every American classicist know about him?

MR: They should know that it is with Scarborough that professional work on languages, modern or ancient, by a person of African descent in this country began. He’s the star, and it’s just not in classics. He was the first black member of the Modern Language Association (MLA) He was also a lifetime member of the APA [now the SCS] for 44 years. His wife, Sarah Cordelia Bierce Scarborough (1851-1933), a college-educated white woman who taught at Wilberforce longer than he did, joined the MLA too. So, they’re actually the first interracial couple in the MLA, although I don’t think the MLA knows that. That’s really important to know—that whatever language you might be studying, Scarborough is the first African American to do that kind of work. He performed all the tasks that we recognize as professional, attending conference after conference with over 20 papers at the APA alone and service of all sorts to the American Negro Academy and the NAACP. He rose to the occasion, not only in his career, but as an educator and a black college president. It is no exaggeration to say that he was an icon, a role model before we had the term.

KO: Scarborough got his degree from Oberlin College (where I now teach). How important was Oberlin to him?

MR: He delighted in having the chance to study there. He had learned to read and write in Macon in secret with black and white helpers. And when he went outside ostensibly to play, he had a book hidden under his arm. So I tell my students, “Imagine going home and risking your life or your teacher’s life if you took your school books out.” Black education was illegal. There’s that courage at the beginning, and his joy at Oberlin to find that no one could stop him from learning everything he could. As a youth, he was one of the people in the city who could read newspapers, knew what was going on, and I think he became deeply fascinated by the power of the printed word, whether it was English, or later Greek and Latin. He studied Spanish for a time at Oberlin and read German; his wife was fluent in French. At Atlanta University, opened under the aegis of the American Missionary Association after the Civil War, he was the only member of the senior class of 1869 and spent some time tearing down Civil War ramparts. He took all the college courses offered at the time. But he could not wait for Atlanta University, which would not graduate a college class (limited to the men) until 1876. So, he cast about for ideas. He thought he might be a lawyer. The Catholic church tried to persuade him to join them. I’m not sure who said to him, “Go to Oberlin.” But in Atlanta he was among pioneering abolitionists who heartily supported black education, and someone must have suggested Oberlin.

KO: We have some of his correspondence from the time he was president of Wilberforce. He was in pretty much constant contact with Oberlin during that period.

MR: He was devoted to Oberlin, and it undoubtedly changed the course of his entire life. After graduation, he thought he’d be able to go home and teach at Lewis High School, the school he attended after the war. But a few months after his arrival as a new teacher there, the school was burned down, in December 1876. He did, however, meet Sarah, who had come with the American Missionary Association to teach in Macon after marriage at age 14 to a Union soldier, divorce at age 19, and a return home with her son to Danby, New York, to her parents to attend college. Where is the movie script, people? You can’t make this up. What amazing lives they had.

In his autobiography, William describes how in 1877 both he and Sarah were individually asked to come teach at Wilberforce. They married four years later, in August 1881 in New York City. I think that going to Oberlin made the Ohio connection easier for him. And no matter how skilled he was, he couldn’t get a job to teach at a white school. Choices were limited to schools like Howard, Clark, or Fisk. In that period, Wilberforce University was the star in the AME Church school system. The AME Church, in fact, supported education across the globe, and Wilberforce was a bustling community.

KO: Scarborough was an active member of the APA throughout his career, but the relationship was not always a happy one, if I remember right.

MR: No – we know, for example, that the APA was not kind to him in 1909. The MLA made him stay in a sordid room, but 1909 was the 40th anniversary of the APA. He was invited to participate, and the meeting was in Baltimore. And he was all ready to go, and there is a letter he quotes in the book [his autobiography] from Francis Kelsey, who’s the secretary. Scarborough says that it was the first time that he suffered “a discourtesy since my connection with the Association.” He was told that since the “Hotel Belvedere will not undertake to serve a dinner at which members of your race might be present... it becomes my painful duty as chairman of the Local Committee to recall our invitation” (Autobiography, p. 207). Details of this situation are found in a letter sent by the APA’s secretary Francis Kelsey (for whom the University of Michigan’s museum was named) which Scarborough preserved among his personal papers. Scarborough doesn’t say much about the event. He remarks that he never went to another meeting in Baltimore. But one wonders if this was the hand of Basil Gildersleeve. He was an apologist for the Confederate side. We’d like to know what kind of interactions Gildersleeve and Scarborough had at these annual meetings – the APA meetings were attended by a very small number of members back then compared to today’s big gatherings, and they must have run into each other. Scarborough never says anything about him, but he had Gildersleeve’s books in his library.

Isn’t that hideous? You’ve been a member since the 1880’s and 1909 you think you’re going to have lunch with everyone else. And at the last minute, you’re informed that you cannot attend.

It’s not just the APA that hurt him, or the MLA. Remember the APA meetings were in July then. Hot, no air conditioning, he’s on a train from Wilberforce making these journeys. He mentions another episode in 1913, at Williams College. Scarborough arrived around midnight and since “the college was some distance from the station,” he asked about hotel accommodations and “they gave me the usual excuse” that all the rooms were engaged. He then asked permission of the traction men to remain in the tool house until morning and he later recalled “I spent a wakeful night in the tool house.” (Autobiography, p. 134). His father had worked for the railroad in Georgia. And I think maybe he took comfort from being in a familiar environment. But he sleeps in his clothes, and he’s going to have to get up the next day and go right to the meeting, but he records no complaints. The irony of it was that his paper was on meals antiquity, on breakfast and lunch, and all he says is he got up to go to the meeting, and he said something, I don’t remember exactly, to the effect of “I knew what it was like to miss one.” No dinner, no breakfast, and going off to dutifully give his paper having slept in the wheel of a traction shed.

KO: Just to wrap things up a bit: in pictures of Will Scarborough, he looks to me like a very stern man. I’m wondering if you have any sense of what kind of a teacher he was?

MR: Yes, that’s hard to know. I do know he had a very subtle sense of humor. You can see it playing out in different places in the autobiography. At Oberlin, for example, he and his fellow students held a special funeral ceremony after finishing Thucydides, an author Scarborough would later present papers about at the APA. His wife was trained in the Pestalozzian method at the Oswego Teaching Institute, a child-centered program using head, heart, and hands based on love, not fear, which was developed in Switzerland. I think they must have had pedagogical conversations. But he makes it clear in his autobiography that he took joy in seeing his students make progress, and that he and Sarah had opened their home to entertain them many times. He probably was stern in a certain way because he was an exemplar, standing up as a black man classically educated in the liberal arts, who wanted to say “This too is your potential.” He carried the enormous weight of that responsibility throughout his life.

A pioneering African-American scholar, William Sanders Scarborough was the first black member of the MLA and the third black member of the APA [now SCS], and served as the President of Wilberforce University for 12 years. His contributions to the profession of Classics had been long ignored until Michele Ronnick published a scholarly edition of his autobiography, The Autobiography of William Sanders Scarborough: An American Journey From Slavery to Scholarship (Wayne State University Press, 2005), and The Works of William Sanders Scarborough: Black Classicist and Race Leader (Oxford University Press, 2006, with a forward by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.). This year, Ronnick has published a facsimile edition of Scarborough’s First Lessons in Greek (originally published in 1881) with Bolchazy-Carducci Press. Scarborough’s autobiography, his collected works and his textbook form a starter kit to understanding black classicism on a professional level in the US. His career heralds a larger phenomenon: the rise of black academics in general, and black philologists in particular, making Scarborough’s works essential reading for the field. SCS members can also read more about early black scholars in the Classics in Ronnick’s recent pamphlet, Twelve African American Members of the Society for Classical Studies: The First Five Decades (1875-1925), published by the SCS.

[1] This interview has been modified from an earlier version, published in the Oberlin Alumni Magazine, spring 2019. Supplementary material has been added from the recorded interview as well as Scarborough’s Autobiography. Thanks are due to Jeff Hagan and Kelly Viancourt of Oberlin for their editorial assistance and fact-checking.

(Header Image: W.S. Scarborough in 1887 (Image in the Public Domain via the the New York Public Library).)

Authors