Young Kim

May 27, 2022

I first met Luis Alfaro at the 2019 annual meeting of the Society for Classical Studies, where he delivered a deeply moving keynote address in which he discussed his adaptations of Greek tragedies and how his plays have brought reimagined ancient stories to new audiences, to provoke social change. This profoundly important event was made possible by a partnership with my former employer, the Onassis Foundation USA, the Classics and Social Justice affiliated group, and the SCS. As many of us will recall, this conference was also marred by the ugliness of racism, which reared its awful head amid an already tense, ongoing conversation about the state and future of our field that has since spilled into the wider public discourse, perhaps for the worse. But there is hope, and I sincerely believe that Alfaro’s work can be one of those mechanisms of change, if only our field would embrace it.

Through a generous grant from the University of Illinois system’s Presidential Initiative: Expanding the Impact of the Arts and the Humanities, my colleague Christine Dunford and I were able to establish the Luis Alfaro Residency Project (LARP), which hosted Alfaro at UIC during his spring 2022 sabbatical semester. Dr. Dunford is an accomplished actor, writer, and anthropologist, among other things, and our collaboration is but a small example of enormous possibilities. We are all deeply aware of the continuing crisis in higher education. The arts and humanities, in particular, must work together to survive. When we initially discussed the prospect of applying for this grant program, the first person we thought of was Alfaro, who was already well-known in certain parts of our campus, especially through a production of his Electricidad in 2018.

We came to the proposal with open minds, only holding close the charge of expanding the impact of the arts and the humanities. In our early conversations with Alfaro, he shared with us a question he had been wrestling with for a long time: why do people in his (Chicanx) community not seek out mental health services? He called his concept “healing the brown brain.” Amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, he has also been thinking about healthcare givers and how they continue to carry unaccounted-for emotional trauma, even as we seem to be moving on so quickly, as if life was back to “normal.” So we had the challenging task of developing a grant application that centered this question and how the arts and humanities disciplines — in this case, theater and classics — might begin to contemplate an answer.

As many of us know from our classrooms, the themes of Greek tragedy can open the door to conversations about our present individual and community wellbeing. Can we break free from what seem to be our predetermined destinies? How do we cope with profound loss and the weight of grief? What unimaginable things might we do when we experience heartbreaking betrayal? Alfaro has taken the questions that arise from the ancient stories so familiar to us and has masterfully reshaped them, drawing on the wisdom that comes from a lifetime of artmaking and activism.

His Electricidad takes Sophocles’ Elektra and explores family loyalty, feminism, and the generational effects of gang violence. Oedipus El Rey interrogates the mass incarceration and high rate of recidivism that both disproportionately affect people of color, as it also demonstrates intimacy, love, and loss amid violence. Mojada is a devastating reimagining of Medea, who, as an undocumented woman trying to make her way in the United States, has suffered sexual assault, economic hardship, and cultural trauma and erasure. Thanks to Rosa Andújar for her award-winning volume that has made Alfaro’s trilogy widely available as a teaching resource.

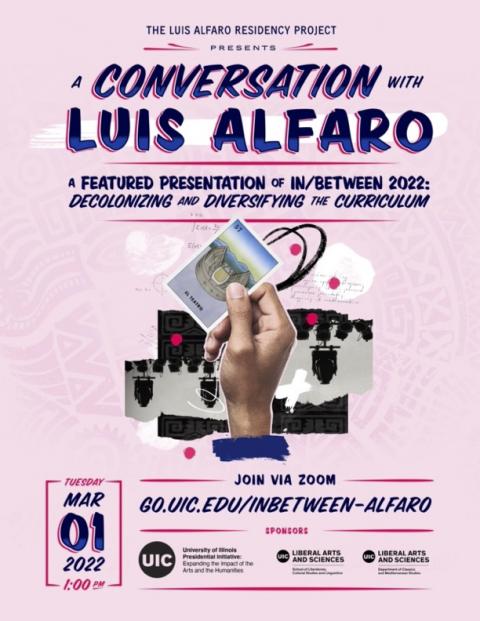

Figure 1: A promotional flyer from the Luis Alfaro Residency Project for "Speaking My Mind."

The centerpiece of the LARP (among other programs) was a series of storytelling and listening workshops — called “Speaking My Mind” — in partnership with UI Health and two Chicagoland community organizations, the Gage Park Latinx Council and the Pilsen Food Pantry. Raising questions that come from ancient tales and using exercises and techniques from theater and performance studies, Alfaro facilitated these sessions with different community groups: healthcare workers at the UIC hospital, healthcare professions students, and people in the predominantly Latinx communities in the Gage Park and Pilsen neighborhoods. The conversations that arose from these workshops — frequently sprinkled with tears, contemplative silences, and healing laughter — revealed just how much trauma we as individuals and communities are holding. These sessions created a space that enabled and empowered its participants—me included—to give voice to the burdens we carry. As organizers, we were very mindful that this project was not therapy — that is a professional service — and that we were not playing the role of therapists. Still, our meetings were therapeutic in their own way and provided a glimpse of possibilities, and they encouraged all to seek help for our mental health challenges.

Now is this “Classics” as many of us practice in our research and teaching? I suppose not. Is what we did really just community outreach with a veneer of classical reception? Perhaps. But these seem to me the wrong kinds of questions to be asking.

We are all profoundly aware of how our field and its associated disciplines are under constant duress, dying on the metaphorical academic vine. And, if we continue on the same trajectory as we have, then “Classics” will only continue to exist in a handful of select, elite institutions. But if we imagine, collaborate, and experiment with how our field can do good, partnering with colleagues in other fields and working with our respective local communities, then we may yet survive, and perhaps even thrive.

Header image: A flyer from "A Conversation with Luis Alfaro."

Authors