Wells Hansen and Adam Blistein

August 1, 2014

I became a Classicist because of Alfred V. Morro (1920-2005, photo below left).

.jpg)

Almost everyone in the state of Rhode Island above a certain age would (a) recognize Al’s name, and (b) be surprised by my statement because he was almost exclusively known as a football and track coach of great success and rare ferocity at Providence Classical High School. If you can remember what college football fans outside of Ohio State thought about the late Woody Hayes, or, more recently, what college basketball fans outside of Indiana University thought about Bobby Knight in his chair-throwing days, you have some idea of Al’s reputation in Rhode Island.

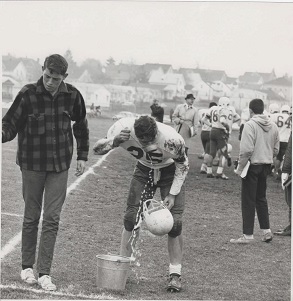

In the background of the photo below right you can see him haranguing his troops in a pose that was familiar to all who knew him. In fact, that photo shows me becoming familiar with that pose because I was an assistant manager on the football team, and I am the young man in the gray sweatshirt with his back to the camera.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s Al was a legendary football player and track and field athlete first at LaSalle High School in Providence and then at Boston College. In consecutive years he played in the Cotton and Sugar Bowls for B.C., and he was captain of its football team in 1941. He went on to a successful career as a football and track coach in Providence and was athletic director at Classical for many years. The School’s athletic complex is named for him. His citation in the Hall of Fame of the Rhode Island Track and Field Coaches Association reads in part: “The State's most successful coach of all time. His Classical H.S. teams were virtually unbeatable over his many years of coaching.”

Despite this eminence, the School District of the City of Providence required him to do more than coach in return for a full paycheck. For many years that additional work was to teach ancient history to ninth graders, and in that position in 1963-64 he introduced me to mens sana in corpore sano. I can't think of a better person to have done this. Al taught ancient history as he did everything—forcefully and idiosyncratically. Among his idiosyncrasies was to offer extra credit to anyone who would read a classical author in translation for 30 minutes outside of class. That extra credit—especially extra credit so easily earned—was pretty attractive. Al also offered extra credit for short reports on ancient civilization, but I rarely took him up on that offer even though the report could be nothing more than an article copied out of an encyclopedia. Instead, since he was good enough to give me an additional reward for something I'd be doing anyway, i.e., reading, that year I went through every Penguin and Loeb I could lay my hands on, usually in thirty-minute segments. In some cases, however, I kept on reading long past the point that the book generated extra credit, just because I couldn't put it down. For example, in Al's system, you could get a credit for each play of Euripides you read, but exactly one credit for all of the Iliad or of Herodotus. I still read all of Herodotus.

That's how I became addicted to classical literature and how, after a number of detours, I became Executive Director of the APA. My high-school Latin teachers ranged from competent to inspiring, but it was Al's encouragement that I sample the entire smorgasbord of classical literature that made me want to keep reading Latin, which I began the same year I studied history with him, and to start reading Greek once I got to college. As I told him while I was still in graduate school, "I wanted to be a history teacher until I met you."

The conventional wisdom is that coaches cannot make the transition from the field, court, or rink to the classroom. I've heard my colleagues who manage learned societies for historians despair of coaches teaching their subject in high school. For years the comic strip Funky Winkerbean made a running joke out of the football coach who shows films in health class because he's incapable of teaching the actual subject matter. Al was twice as fearsome as Funky's coach, but as a teacher—in a far more complicated subject—he was more than competent. He brought a then fifty-year-old textbook to life, and he developed a system that would entice your average grade-grubbing fourteen-year-old to develop a familiarity with the ancient world that no textbook, and especially not a moldy one, could provide.

Why did he bother? He was a fixture in the school and could have time-served his way through those ancient history classes. In fact, a few years after he taught me, he moved on to an administrative job whose purpose I never completely understood that took him out of the classroom altogether. I'm sure part of the explanation was that he valued his Italian-American heritage, but he didn't emphasize Roman history or culture over Greek. I suspect his own good solid Catholic classical education, first at LaSalle and then at B.C., gave him a special appreciation for the subject. Mainly, however, I think he was a man who demanded excellence of both himself and of his students, wherever he or they happened to be. That's not a bad lesson to have picked up along with a taste for Aristophanes, Herodotus, and Tacitus.