Clara Bosak-Schroeder

August 9, 2022

When I learned that I would be teaching my department’s graduate Greek survey in Fall 2021, I promptly burst into tears. The assignment was not what I was expecting; more painfully, it brought up all the barely suppressed memories of my own survey experience.

In one sense, that experience had been a success. It transformed me from a glacially slow reader of Greek into a slightly faster one, familiar with a range of authors and genres and capable of passing my Greek qualifying exam. It also left me with an enduring sense of inferiority, even fraudulence. I didn’t make it through a single one of our assignments (the standard 1,000 lines per week). I never felt in command of the language or my own learning. The fact that I had improved seemed more like a happy accident than an effect of the curriculum, let alone something I could be proud of. For years afterwards, even post-graduation, I would wake up wondering how many lines I had to read that day and then calculate by how far I would fail.

This might seem like an extreme reaction, but from what I can tell, it’s not uncommon. Greek and Latin Surveys, the foundation of Classics graduate curricula in the US, leave many people feeling ashamed of their language skills.

After drying my eyes, I called the Head of my department. Did I really have to do this? Did he really want me to? Without calling myself an imposter, I reminded him how little elementary and intermediate Greek I had actually taught. Maybe this was an assignment for someone else. “You’ll be fine,” he said. “They’ll love it.” It was a short call.

Resigned, I decided to recast this disaster as an experiment: could I teach survey without brutalizing my students?

I started by considering the particulars. Since I teach in a small program, we condense surveys into one semester per language and offer them only sporadically. This means that our surveys are filled by people who have chosen to be there, usually to prepare for a qualifying exam. Desire — or fear, at least — propels students into the class, not the dictates of an advisor.

But the infrequent offering of survey also means that students display a huge range of preparation. My class of 14 spanned students in years 1–5, including two who had already passed their Greek exam. Some of the first-year students were accustomed to reading large amounts of Greek in senior seminars or mixed grad/undergrad reading classes. Others had never translated more than 60 lines per session.

Because it represents such a leap in required reading, even surveys composed entirely of first- or second-year students produce a kind of one-room schoolhouse. Part of the pain students experience comes from the fact that this reality is not acknowledged. The survey is constructed as something that all students should be be able to complete, regardless of previous training. If they can’t keep up, the implicit message is that they don’t belong.

I did two big things to change this dynamic. First, I cut the required reading by half, from 1,000 lines a week to 500, or about 10 pages of an Oxford Classical Text. This would represent a doubling or tripling of what some students were used to, while still (I hoped) challenging more advanced students.

Second, I framed this amount — and students’ command of morphology, syntax, and vocabulary — not as a universal benchmark everyone had to hit, but as a tool for measuring improvement. I had students assess their current skills and set future goals in reflections at the beginning, midpoint, and end of the semester, and every week after the quiz. I made it clear that I was interested more in their progress than their raw performance; they would be competing not with each other but with themselves.

Of course, students were also aware of each other’s performance and made, I’m sure, frequent comparisons to their peers, but I used these reflections to train their focus on their own learning.

500 lines turned out to work well for this diverse group. Halfway through the course, 8 of the 14 students reported that they were reliably getting through half or more of each assignment, while the rest finished three-fourths or more. (All statistics and quotes in this post are taken from student feedback and used with the permission of the entire class.) This number declined at the end of the semester, partially from the stress of final projects, but also because I encouraged students to tailor their reading to their circumstances. Students preparing for a qualifying exam, for example, read less Greek ahead of time to test their sight-reading abilities in class. Others decided to focus on quality and control rather than quantity: “I felt that going slower and understanding syntactically and narratively what was going on in the Greek would help me more down the line than just attempting a mad dash to the finish the Greek each week.” Yet others found that they wanted to speed up their reading by using digital lexica and sites like Perseus. As long as students kept me in the loop, I was fine with these modifications. No technique was shamed or forbidden, as long as it related directly to a learning goal.

To increase buy-in and a sense of communal endeavor, I also invited the class to help me shape our syllabus and make midterm modifications. A poll before the course began asked what they were eager to read, what they had read before, how they felt about going off the reading list, and anything else they wanted to incorporate into the class. This poll led me to hew fairly closely to our reading list, while adding a couple authors by request (e.g., Athenaeus).

Also at the students’ request, I incorporated sight reading into our weekly routine, drawing passages from a less-read but relatively straightforward prose author, Diodorus Siculus, I knew I could prepare easily. Students commented that they would prefer to have read different authors at sight over the semester; I agree that this would have been better, but I knew it wasn’t something I could sustain.

Students’ primary goal in taking the class was to improve their Greek, but it is also the responsibility of a survey (as I understand it) to teach something of the history of literature, how particular texts fit into the development of genres and themes across time. To support this aspect of the class, I divided our meeting time into two sessions. On Wednesdays, students would prepare Greek, take a quiz, and spend the rest of class translating. On Fridays, they would prepare scholarship and perhaps a translation of the text we had started Wednesday, hear a presentation from a peer on a text we weren’t studying, and sight read. This meant that the greatest interval between classes (Friday to Wednesday) could be devoted to their harder task, leaving the two days between classes for scholarship. As a result, students weren’t tempted to skip the scholarship in favor of reading more Greek.

This rhythm was also helpful for my own preparation. As a slow reader with other commitments, I never attempted to read the entire Greek assignment I had set. Instead, I chose passages for the quiz and for us to translate together and prepared them to a high level. After receiving midterm feedback, I also provided time for students to work together in groups on problem spots that fell outside the focus of our in-class translating. They could call me over to troubleshoot particularly difficult points of grammar, but usually worked things out for themselves.

Our discussions of the history of Greek literature were anchored by Tim Whitmarsh’s Ancient Greek Literature, the only text students were required to buy, and supplemented by articles and book chapters relevant to that week’s Greek reading. Since I wanted to expose students to the latest conversations, I drew almost exclusively from the last 20 years of scholarship, but my selection was, at best, eclectic; sometimes we had great discussions, but there were often significant divides either between what I and they found interesting, or what the younger and older students in the program had enough background to understand.

Whitmarsh was a hit, but in the future, I will probably supplement with more “classic” articles and book chapters, even if authored primarily by white cismen, and reduce this scholarly reading to make more room for sight reading, which students found more valuable. I would also like to develop better resources for students just starting to read scholarship. We talked about strategic vs. immersive reading at the beginning of the semester, but there is more I wish I had done to explain the rules of the genre and to externalize my own practice.

In addition to midterm and final projects (which I won’t describe for the sake of space), students took weekly low-stakes quizzes that we translated and corrected together in class. This provided immediate feedback and spared me the chore of marking them. Even though quizzes were only graded for completion, students reported that the fear of embarrassment when we translated motivated them to keep on top of homework.

I modeled the midterm and final on our department’s qualifying exams, to give students experience with the format. Like the quizzes, each exam (completed at home) was followed by a reflection. This reflection asked students to correct their exam, look for patterns both in what they had missed and gotten right, submit lingering grammar questions for me to clarify, and, finally, put their performance into dialogue with past assessments to measure improvement. I first graded these exams straight, following our department’s rubric for qualifying exams, and then added points for improvement based on these reflections. This process gave students a practical sense of whether they were close to being able to pass a qualifying exam and reframed the exam itself as a tool for understanding their own learning.

From feedback and evaluations, this approach seems to have worked for most students. As one first-year student commented: “I was super nervous when I first signed up for this class because I knew it would be a lot of work and a challenge, so thank you for making it a manageable, good, and fun challenge.”

Yet there were some who found the whole conceit of the survey an obstacle. When asked at the end of the semester how the course could be improved, one student commented: “I would suggest a reasonable amount of reading. I understand this is a survey course but asking an unreasonable amount of work from grad students is deterring people from graduate school, we don’t learn much when we have too much work, and it affects us in our personal lives.”

I inherited the “boot camp”-style survey and I’m proud of the strategies I developed to make it more of a positive than a negative experience. But departments like mine should step back and ask themselves why they have this course on the books. Is it just because it’s the way we were trained? Or do the unique demands of survey play a unique role in our curriculum?

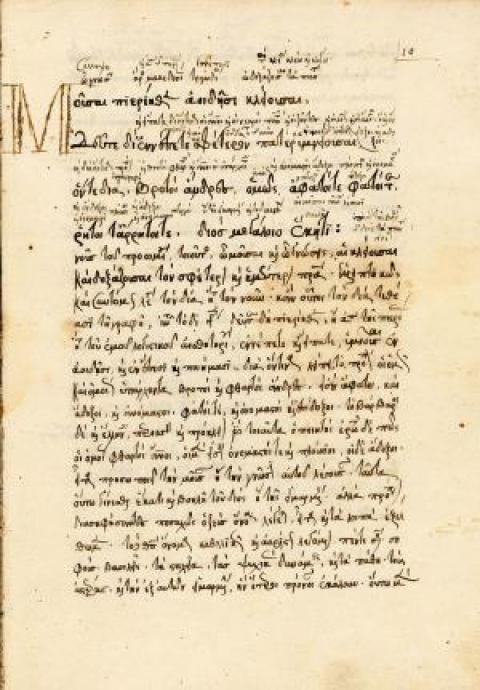

Header image: Manuscript page from the opening of Hesiod's Works and Days. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Authors