Liz Penland

March 21, 2019

How can we forge better and lasting connections between the ancient Mediterranean and modern Chinese culture? At the end of the last school year, I had the occasion to sit down with my student, Hongshen Ken Lin (林鸿燊) to talk about his experiences in Classics. Ken was at the end of his senior year and had been accepted early to Harvard, where he planned to combine his love of Big Data and digital humanities with something equally remote and challenging: the study of Roman and Greek Antiquity.

According to Ken, he became interested in studying Latin through a family trip to Rome combined with a freshman history class in the Ancient Mediterranean at his new US school. That was the first time he realized that Latin existed. He had not had much exposure to Roman and Greek history in China.

Back in school in China, all the history courses are really, really structured. Everybody takes the same classes. So when we learned about Rome and Greece, it was a really brief introduction, and then we immediately moved on to the next subject or period. It was like a quick snippet.

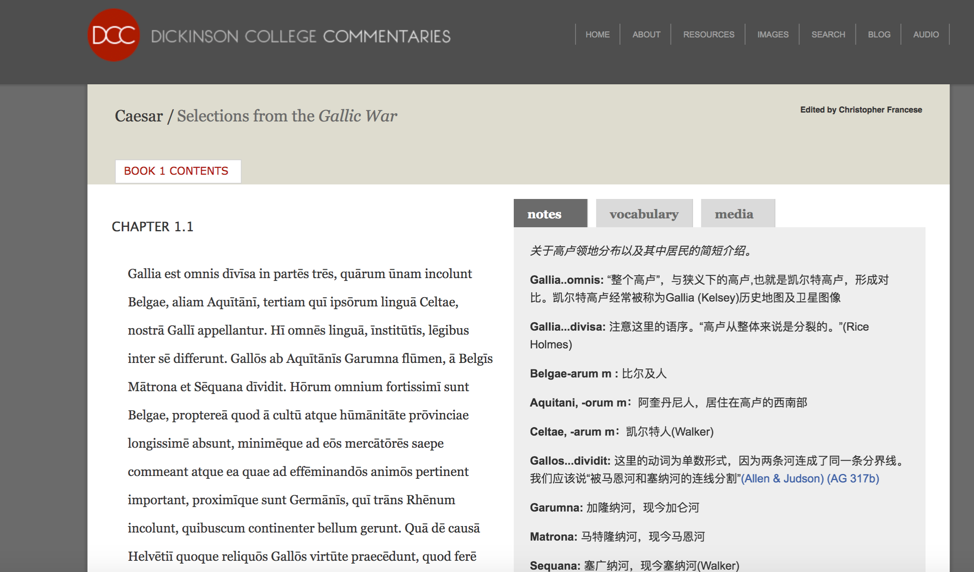

While studying Latin, Ken became engaged in a project I was starting—translating and editing a Mandarin version of the notes and vocabulary to Caesar’s De Bello Gallico for the Dickinson College Commentary online.

With a dedicated team of fellow students and adult advisors, Ken painstakingly translated the challenging and often arcane language of Caesar and English commentary style. At first, when asked to collaborate with other students on the translation, he found the idea of group projects unfamiliar. By the end of the project, however, he’d come to see teamwork in a different light.

Especially by the end, when we were trying to focus on finishing the work, everybody collaborated. It was just wonderful to see everybody working hard together. A lot of energy going on. That definitely helped me to develop my collaboration skills.”

The group collectively navigated textual meaning through the original Latin and the English intermediary to the destination language of modern Mandarin. The multilingual group made style decisions along the way: how to represent English names, what to do with technical terminology, how to make the end result readable at the high school and early college level. The group celebrated the launch of the version into the wider oceans of the internet by submitting it on January 28, 2017. This was the first day of the Lunar New Year and also Ken’s 17th birthday.

In the process of translating the commentary into Mandarin, Ken met other students who shared his engagement with Classics, including students who were also born in China and studying at American boarding schools. Several of these students gathered in a We-Chat group Ken started to spread information about Greco-Roman Classics to a Chinese audience. Some ended up working with Ken as the group launched a series of posts from the English-speaking classics blogosphere with Mandarin descriptions or translations. The content contained a number of articles from Eidolon with Mandarin summaries—Ken says a conversation between Harry Potter and Socrates was particularly popular (see Caroline Bishop, “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phaedrus,” Eidolon [November 10, 2016]).

For his senior independent project with me, Ken chose to contrast the travels of Marco Polo to the court of Kublai Khan with a new Chinese infrastructure plan. He read accounts of the medieval trading voyage across Central Asia in tandem with the Chinese government Silk Road initiative, also known as “One Belt, One Road” (一带一路), a massive undertaking to link more than 80 countries via land and sea routes. As I write this post, Italy has just indicated intentions to endorse the initiative, bring the modern link to Marco Polo’s travels full circle.

When I asked Ken about the One Belt Initiative and the value of studying the past, he said,

The past really gives us more confidence for the future. And China’s One Belt, One Road initiative, I think that’s a good evidence of what collaboration can create for people and countries. It’s not fully complete yet, people are still working on it, but I think it’s looking very optimistic. That really stems from the willingness to open oneself up to other countries and connect.

He also said that his project had made him much more interested in international relations and foreign policy.

When asked about his perceptions of the fields of Classics and the challenges of being not only open, but welcoming to people from diverse background, Ken touched upon his recent college tours and his work with Aequora (through an internship with Paideia). As he put it,

The landscape of classics is really shifting nowadays. It’s becoming more accessible in terms of teaching--Paideia, for example, is doing a lot in accessibility, making it more available to students not just in prep schools or colleges, but also available in less privileged areas.

However, he remarked that there’s much more work to be done.

I realized that Classics is getting more accessible in the US but it still needs more work. In China, it’s even worse. A lot of people have never heard of this subject, and also only a couple of universities offer the program.

Ken was enthusiastic about the definition of Classics expanding to encompass not just Greco-Roman Classics, but also texts in Sanskrit and classical Chinese, which he studied before coming to the US.

I noticed a lot of similarities between Latin and classical Chinese. I actually did a section for that in the Aequora textbook--I did a sidebar to compare Latin to classical Chinese.

One of the primary similarities he noted was the ability of one written word to encode a wealth of details, in the case of Latin through inflected endings. As he put it:

It’s similar in classical Chinese -- one word can convey so much information. I think it’s because paper and writing instruments were expensive and there was a need for language to be very concise and also be meaningful.

When I asked Ken where a person interested in studying the Chinese classics might start, he cautioned that modern Mandarin is hard enough to learn, much less classical Chinese which is difficult even for native speakers. He recommends reading the Lun-Yu, or Analects of Confucius, in translation. “By looking at that text, people can get a good idea of what the core values of Chinese culture are and also what the past looked like.”

Ken is now a freshman at Harvard, active with Harvard-Radcliffe Chinese Students Association, the Asian-American Dance Troupe, and the Harvard College China Forum, whose annual conference will be held this April under the heading “A Global Community, One Shared Destiny.” Ken is a Venture Associate with the Harvard College China Forum and will be a speaker at this event which has historically drawn up to 1200 participants and over 100 speakers to discuss “challenges, trends, and issues affecting China, the forum aims to engage leaders in business, academia, and politics in discourse that will offer insights and generate new ideas.”

Header Image:Young female polo player (Early 8th Century CE, Terracotta, engobe, and polychromy. Tang Dynasty. Musée Guimet. MA 6116 à 6121) (Image via Wikimedia).

Authors